In the previous article, we read about a rather peculiar puzzle, namely, the fact that the greatest technical works of Indian astronomy are all attributed to divine origin, having no professed human authors.

In this present article, we will examine the most widespread misconception among the general public regarding Indian astronomy, namely, the Kali-Yuga.

Though the term Kali-Yuga is very well known in India, at least among the Hindus, it is usually spoken of with a mythological or philosophical connotation. That it has an astronomical meaning as well is known only to a few, and those few often have only a partial understanding of what it actually represents.

We will attempt in this article to clear up that misunderstanding, and in the process examine some of the fascinating frameworks of time created by the ancient Indians, unmatched by any other culture in the ancient world.

Misconception #2 – The Kali Epoch

It is a natural instinct in Man to seek out periods of time when things return to their original positions.

The Day (Sun), the Month (moon) and the Year (seasons) are everyday examples of such cyclical periods of time.

A natural progression in the maturing science of a society is to tread further on this path and seek out greater and greater cycles of time, with the ultimate objective of determining the largest possible cycle, in which every cyclical variation in the universe returns to its starting point.

In the early years of the Christian era, for example, their scholars sought out cyclical periods in Easter computations, in which the largest cycle turned out to be 57 million years long!

Now, the Easter computation, though quite intricate, involves only the Sun and the Moon.

In contrast, the time-cycles of Indian Astronomy take into account every heavenly body, including the Sun, the Moon, the five visible planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn), their Apogees, their Nodes, and the earth’s precession.

Needless to say, employing such a plethora of variables results in a large number of time-cycles in Indian astronomy, which vary in size from the small, to the large, to the enormous, to the mind-bogglingly ginormous cycles.

In spite of all this variation and complexity, quite remarkably, an outstanding feature of Indian astronomy is its unity in diversity. It is a unified and complete cosmological framework, from start to end.

If it were only that, a cosmological hypothesis by itself and nothing else, it would not be such a big deal. But, the cosmology of Indian astronomy has been skillfully woven into everyday mundane astronomy, to produce a neatly unified system in which the minute, the mid-sized, the big, and the enormous all coexist in harmony.

No other ancient culture comes remotely close to the panoramic unity and completeness that is found in Indian Cosmology.

The Great Indian Cycles of Time

The universe runs in cycles of time: small, medium, big, huge, and immense. This fundamental concept is at the root of Indian Cosmology.

Starting at the lower end of the time-scale, the smallest unit found in Indian astronomy is in the Microsecond range (a millionth of a second). From this remarkably small scale, the time-periods build-up, step-by-step, to Milliseconds, Seconds, Minutes, and Hours. Twenty-four hours then make a Day, 30 days a Month and 12 months a year.

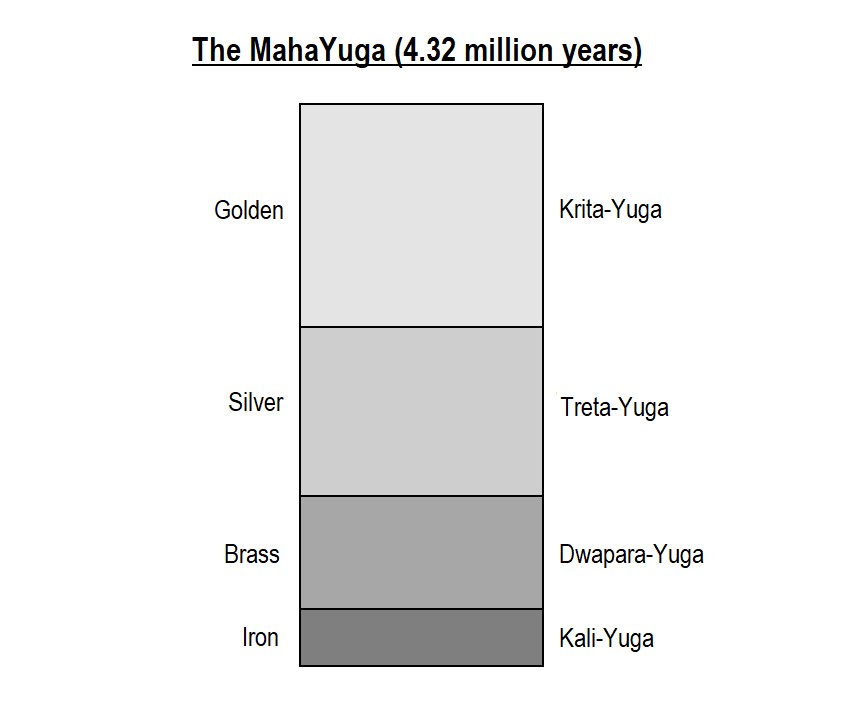

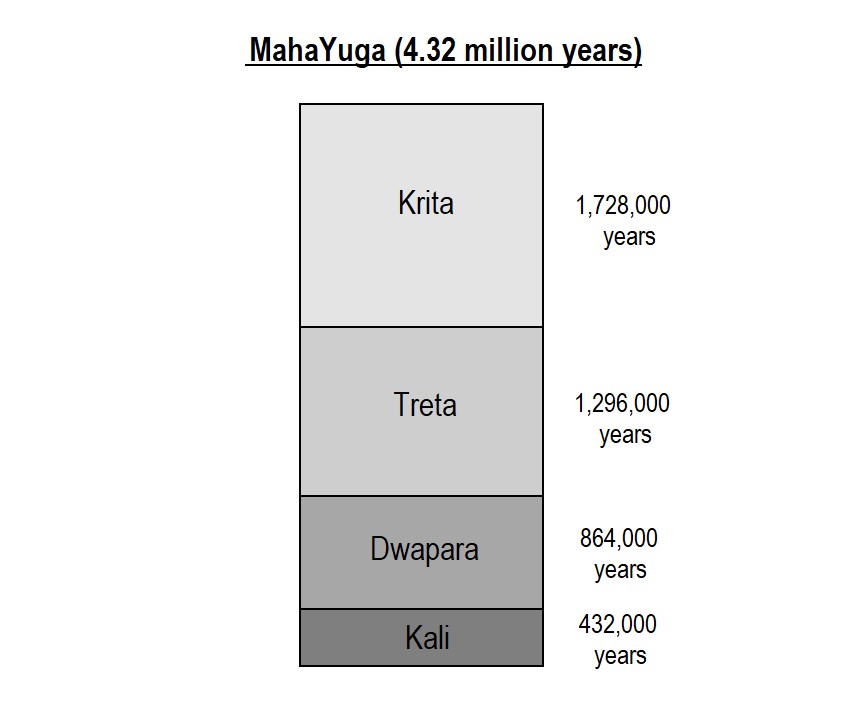

Proceeding further, 360 human years make a Year of the Gods, and 12,000 of these divine years make a MahaYuga (great-age) of 4.32 million years. The MahaYuga is divided into 4 Sub-Yugas, in the ratio 4:3:2:1, as shown in the figure below. We will see more of these Sub-Yugas later in the article.

From the MahaYuga is built the first of enormous time-scales, namely, the Manavantara, which is composed of 71 odd MahaYugas, totaling about 308 million years, as shown below.

From the Manavantara is then built the great astronomical period, the Kalpa, composed of 14 odd Manavantaras, totaling to 4.32 billion years.

The Kalpa, also known as a Day of Brahma, is composed of 1000 MahaYugas. It is the largest Indian time-cycle that is based on actual astronomy.

The Kalpa is of great significance to Indian culture, and also of immense interest to historians of science because the Day of Brahma (DoB) represents the Indian version of the Big-Bang Theory.

According to mythology, at the start of the DoB, the Creator-God Brahma awakens from sleep and begins the process of creation. The material for creation comes from his own body. The DoB lasts for 4.32 billion years.

At the end of the DoB, Brahma absorbs his creation back into Himself, and nothing remains.

The DoB is followed by the Night of Brahma, which is of the same length as the DoB. Brahma is asleep during this period, and nothing exists.

At this point we may begin to wonder – do these Indian time-cycles go on forever, or does it finally end somewhere?

There are indeed further time-cycles beyond the Kalpa, but those are all clearly imaginary, and not based on actual astronomical cycles. They have been included in the Indian cosmological framework, most likely, for the sake of completion.

The Year of Brahma is composed of 360 of Brahma’s days and nights, totaling 3.11 trillion years. Further, Brahma’s Lifetime extends to 100 years, giving us 311 trillion years.

After the demise of a Brahma, another Brahma comes into being, and the cycle continues, forever. Western scholars like to call this ‘the Indian love-affair with infinity’.

Finally, to round out the cosmological framework, the entire lifespan of a Brahma is equal in duration to a mere blink of an eye of Mahadeva, the infinite, immortal Being.

Time taken for Creation

According to Christian scripture, God created the universe in six days flat and took a well-deserved day off on the seventh.

Lord Brahma, in contrast, was either a big-time slacker or a very meticulous worker, because, according to the Surya Siddhanta, he took over 17 million years to get the job done!

While the Christian creation fable has obviously no astronomical bearing, the Indian legend of Brahma’s time-to-create may have an astronomical significance, as we will see further below.

“You are Here”

As seen above, universes are created and dissolved on a daily basis by Brahma, throughout his lifetime. The Kalpa, of 4.32 billion years, is the maximum lifespan of a universe. An interesting question is this – what, according to Indian astronomy, is the age of our current universe?

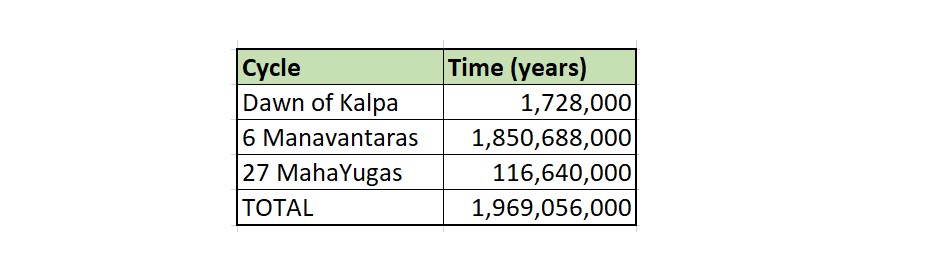

Per Indian texts, six Manavantaras have passed in the present Kalpa. Of this, the seventh, 27 MahaYugas have passed. Finally, of this, the 28th MahaYuga, the Golden, Silver, and Brazen ages are past, and we have recently entered into the Iron (Kali) age.

A quick total shows us that 1.97 billion years are past for our current universe, which amounts to 45% of the allotted time for the Kalpa, with another 2.35 billion years to come (phew!).

Incidentally, modern science has estimated the current age of the universe to be somewhere between 10 and 14 billion years. While the Indian estimate of 2 billion is in the neighborhood, though not very close, it definitely beats by a mile the Christian estimate of 6000 years.

The Twilights

Before moving on, it must be mentioned that these Indian time-cycles are actually a lot more complex than described so far.

Each cycle has, for example, twilight periods, dawn and dusk, that occur at the beginning and at the end of the cycle respectively. The figure below shows the case for Kali-Yuga, whose total duration is 432,000 years.

We are currently about 5100 years into the dawn of Kali.

We will examine in a future article these various time-cycles and their astronomical significance and other details. For now, let us focus on the matter at hand, namely, the Kali-Yuga.

Because the Yuga system is based on Mean-Motions, an understanding of Mean and True motion is essential.

Mean and True Motions

As most readers will know, heavenly bodies like the Sun, Moon, and Planets move with varying speeds – they are faster at times, and slower at other times.

The mean-speed of a body is defined as the average speed of the body. The averaging, in astronomy, is carried out over a very long period of time (many centuries). The longer the averaging interval, the more accurate the mean-speed value.

Now, once we have the mean-speed for a body, we can define a hypothetical Mean-Body, which always travels at this mean-speed. The motion of such a hypothetical body is called the Mean-Motion.

In contrast, the True-Motion of a body is the actual motion of the body, which, as we mentioned, varies with time.

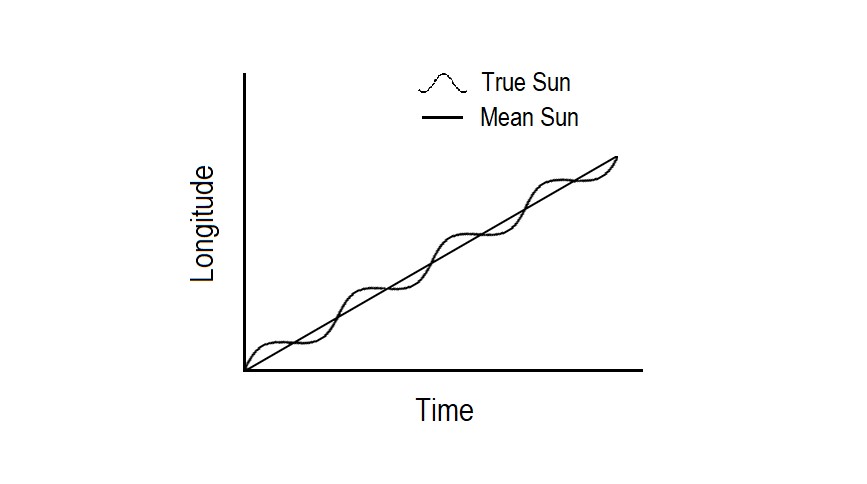

Taking the Sun as an example, the figure above shows its Mean and True motions. It can be seen that the Mean-Sun moves at a constant speed, its longitude increasing linearly with time (straight line).

The True-Sun (wavy line) is seen to move with varying speeds, sometimes lagging behind the Mean-Sun, and at other times going ahead of it. In either case, the True-Sun always remains close to the Mean-Sun, never straying more than ±2 degrees away from it.

From the figure, we can grasp two simple points about the Mean-Body hypothesis.

Firstly, the True-Body is always found close to the Mean-Body. So, the Mean-Body is a good first-approximation for the position of the True Body.

Secondly, because it always moves at a constant speed, the Mean-Body position is very easy to calculate. Say you know the position of the Mean-Sun at time T0, and wish to determine its position at another time T1. Simply multiply the time difference (T1-T0) with the Mean-Speed of the Sun, and add the result to its position at T0.

In fact, a standard technique in astronomy (both ancient and modern) is to first determine the Mean-Body position, then apply a small correction to obtain the True-Body position. How to find that small correction is, of course, a complicated affair, which we won’t go into here.

Hopefully, the reader has now grasped the significance of Mean-Motion, and its utility for the astronomer. Indeed, mean-motions form the backbone of any astronomy.

Mean Motions in Indian Astronomy

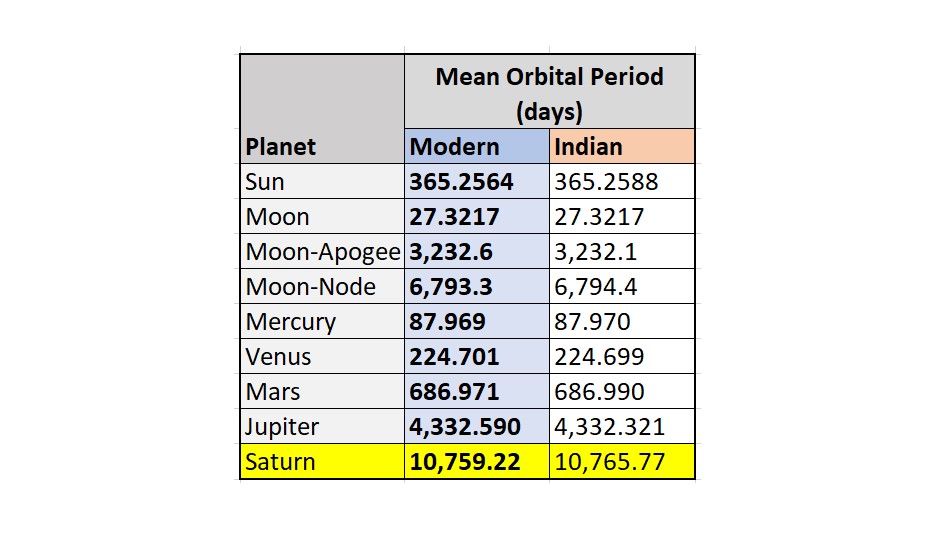

The table below shows the mean-motions of various heavenly bodies, as given in the Surya Siddhanta.

The word ‘revolution’ denotes a complete orbit of 360 degrees.

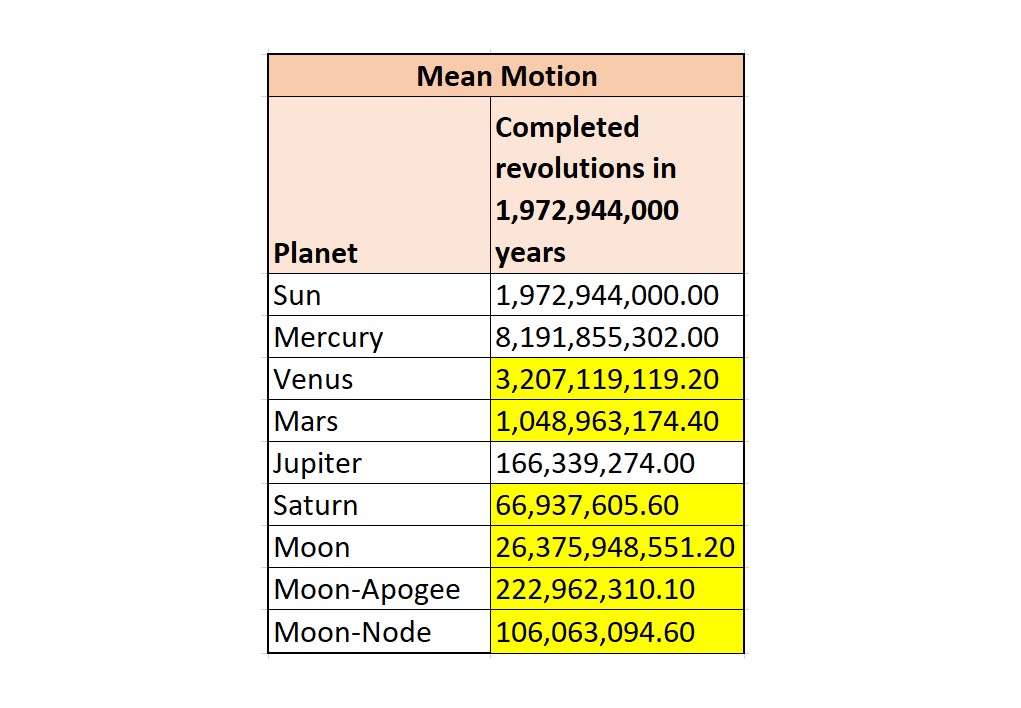

The Table clearly shows us the astronomical significance of the MahaYuga – it is the interval of time when, by their mean-motion, all planets and the Moon’s Apogee and Node return to the starting point.

The word ‘Yuga’, like the word ‘Yoga’, comes from the root ‘Yuj’, meaning ‘to join together’. A MahaYuga is thus a ‘Great Joining’ of all planets, including the Moon’s Apsis and Node.

Just for fun, in the Table below, let us convert these planetary revolutions per MahaYuga into mean orbital speeds for each planet and compare the results with modern values.

We are pleasantly surprised to note the substantial accuracy of the ancient Indian mean-speed data, especially that for the Moon.

Saturn, it appears, is the odd man out, with a not-so-breathtakingly accurate value. But note that planetary mean-speeds are not universal constants. They do change by small amounts over time. These Indian values are thousands of years old.

With that background out of the way, let us now focus on the main topic – the Kali Yuga.

The Start of the Kali

As we have seen in a previous figure, the Kali-Yuga is a small fraction (one-tenth) of a MahaYuga.

We know that all planets and the Moon’s Apsis and Node come together in a MahaYuga. The question we are curious to investigate is as follows: Is there anything special about the Start of the Kali Yuga? Are the planets, for example, in some special configuration at that instant?

Let us check out the mean planetary positions at the start of Kali.

The calculation to find planetary positions at Kali-Start is fairly simple. At creation (beginning of Kalpa), all heavenly bodies are at the origin, from which they start their motion.

We first add up the total time passed from the start of the Kalpa till Kali-Start, and then multiply that result by the mean-speed of each planet. That will give us their position at Kali-Start.

Total time passed since the beginning of the Kalpa, till our current MahaYuga, is as follows:

To this, we need to add the Krita, Treta, and Dwapara yugas that have already passed in our current MahaYuga.

And so we have: 1,969,056,000 + (1,728,000 + 1,296,000 + 864,000) = 1,972,944,000 years.

Now, let us see where the mean-planets are after this duration. The results are shown in the table below.

Oh, this is disappointing. It looks like only the Sun, Mercury, and Jupiter have completed whole revolutions in this period. The rest have completed only a fractional part of their revolutions at Kali-start and are not at the origin. Hmm… nothing much to get excited about here.

Hey, but wait! We forgot to subtract Brahma’s time-for-creation (17,064,000 years) from the total time. Doing that, we get 1,972,944,000 – 17,064,000 = 1,955,880,000 years.

Repeating the above calculation for this new value, we get:

Ah, much better. We see that at Kali-Start all the planets have indeed completed a whole number of revolutions. Only the Moon’s Apsis and Node have fractional revolutions.

So, folks, we have here an astronomical definition for the start of the Kali Age: 1) All mean-planets are at the origin, having completed a whole number of revolutions. 2) The Moon’s Node is half-a-revolution (180 degrees) away from the origin. 3) the Moon’s apogee is one-fourth of a revolution (90 degrees) away from the origin. We will call this the Kali-Configuration.

The Mathematics of Conjunction

Before we go further, a small detour into the mathematics of conjunctions may be useful.

Say we have two planets A and B, which have mean orbital periods of 3 and 4 years respectively. Their Lowest Common Multiple (LCM) is 4×3=12. Therefore, once every 12 years they will come together in conjunction at the origin.

Now, what if the orbital period of A was not exactly 3 years, but say 3.1 years. How often will the conjunction take place in this case?

We first make the decimal into a whole number by multiplying with 10, i.e. 3.1×10 = 31. Then we multiply 31×4=124 whole years.

Going further, what if the speeds were 3.1 and 4.1 years respectively, then the conjunction period becomes 31×41=1271 whole years.

As you can see, as the number of decimal digits in the mean-orbital-speed becomes greater, the conjunction time in whole years grows exponentially longer.

Now consider the actual mean-orbital periods (in days) of the Sun, Moon, and planets (using 6-digit precision):

Sun = 365.258757; Moon = 27.321674; Mercury = 87.969702; Venus = 224.698569; Mars = 686.997494; Jupiter = 4332.320653; Saturn = 10765.773075;

With so many decimals in each variable, as you can imagine, an exact-conjunction of the Sun, Moon, and the five planets would take such a long time as to make the entire age of the universe look like 2 seconds. We can therefore safely declare that such an exact-conjunction of all planets is practically impossible.

That said, we can still consider what we call a near-conjunction, which is what the founders of the Indian system had in mind when they rounded the planetary mean-speeds to the values they used.

We do have to decide what qualifies as ‘near’ though. For now, we will use 20 degrees.

So, we will look for near conjunctions where all mean planets come within plus or minus 20 degrees of the mean-sun.

Computer Simulation to Find Possible Dates for the Kali-Configuration

Thankfully, in these modern times, we can use the enormous power of the computer to scan and locate likely dates (past or future) that match the Kali-Configuration.

That will help us answer the question of whether there really was a Kali-Epoch, or was it simply an imaginative creation of the Indian philosophers.

We will scan from 4700 BC in the past, to 4700 AD in the future, looking for any dates where a near-conjunction may be found for the Kali-Configuration.

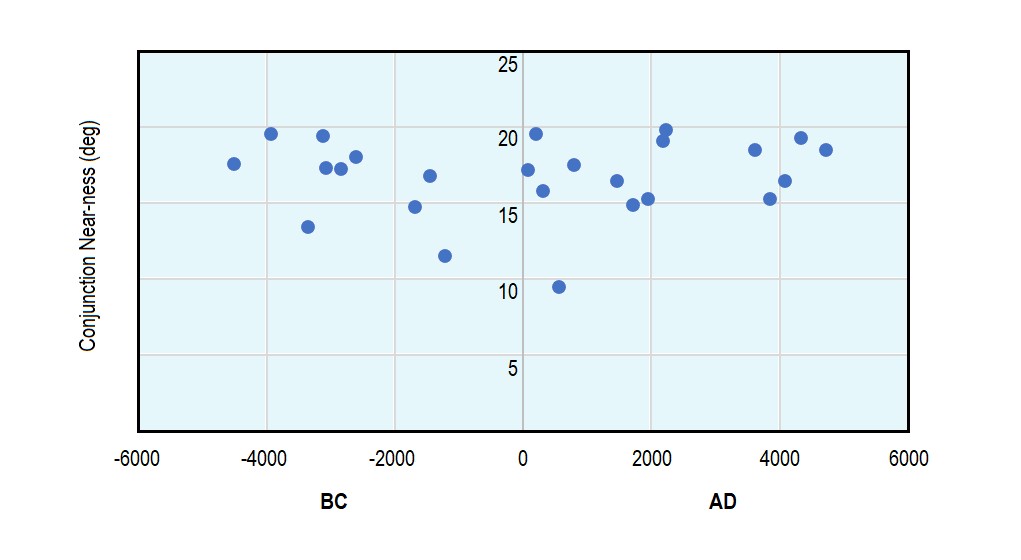

In the first test run, we will ignore the Moon’s Node and Apsis, and focus only on the planetary conjunctions. The results are shown below:

The plot shows nearly two dozen dates found in the past and future that match the Kali Configuration for planets.

Most of the dates are in the nearness-range 15-20 degrees, with the best match being that for 571 AD, where all the mean planets were bunched as close as 10 degrees from the Sun.

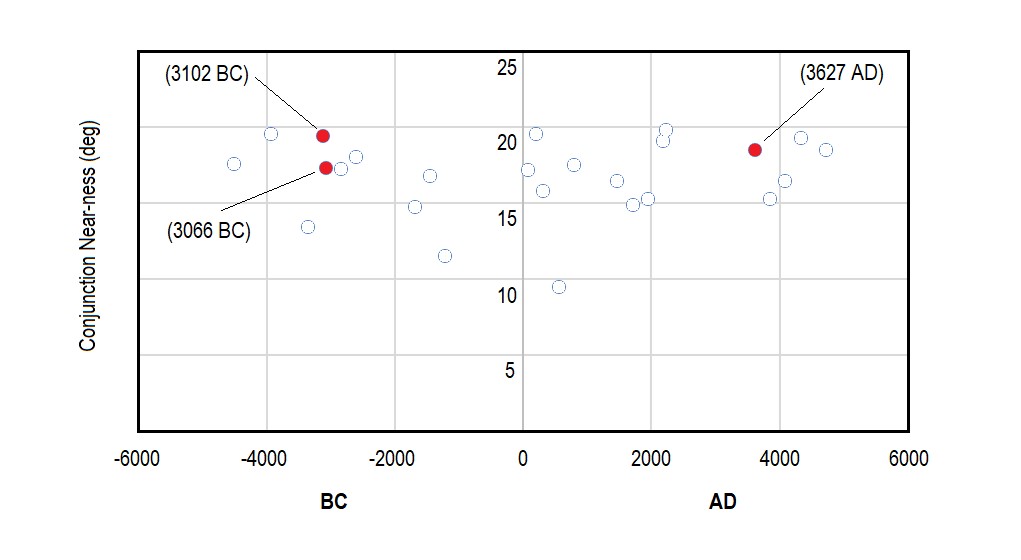

For the next test run, let us apply the conditions for the Moon’s Node and Apsis as well, and see what dates get eliminated and what dates remain.

We see that of the two dozen results, all but three have been eliminated, as shown below.

Of these three remaining (red dots), one date is in the future (3627 AD). We will ignore that.

Let us compare the other two (3102 and 3066 BC), to check which one is a better candidate for the Kali-Start.

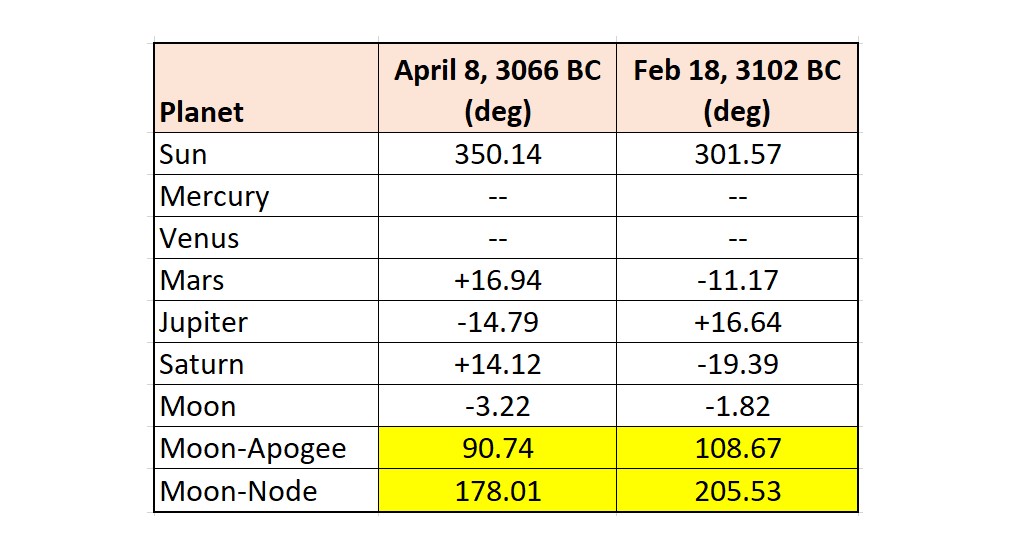

The table below shows the position of the mean-Sun and the differentials from the mean-sun of various planets. Note that the mean-motion of Mercury and Venus is the same as the mean-Sun, so those are ignored.

We note from the Table that of the two candidates in the past for the Kali-Start date, the 3066 BC date is easily the better one.

Recall that according to the Kali-Configuration the mean planets (Sun in this case) are at the origin (0 or 360 degrees) at Kali-Start. We see that the mean-Sun of 3066 BC is much closer to the origin (360) than the 3102 BC case.

Further, for the 3066 BC date, the Moon’s Apogee and Node are strikingly close to 90 and 180 degrees respectively, as required by the Kali-Configuration, than those of 3102 BC.

Thus, without a doubt, of the two cases, April 08, 3066 BC is the clear winner for the Start of Kali.

Aryabhata and the Start Date of Kali

In the current and former literature on Indian Astronomy, going back a thousand years and more, the Feb. 18, 3102 BC date has always been the widely accepted date for the start of the Kali era.

In a popular misconception, the 3102 BC date is often associated with the revered Aryabhata, and it is thought that it was he who first suggested that date.

But, on checking Aryabhata’s work, we realize that he did not actually specify any date for the Kali-Start. He merely stated that 3600 years of the Kali had passed when he was 23 years of age. And, of course, no one knows for certain when Aryabhata was born.

The Mahabharata War and Lord Krishna’s Passing

Now that we have two dates competing that are vying for Kali-Start, let me introduce one other item that may add to the intrigue. These two dates are 36 years apart.

3102 – 3066 = 36 years.

According to the Mahabharata, Lord Krishna passed away 36 years after the great war, and his passing marks the start of the Kali Age.

Thus, a possible scenario is that 3102 BC actually marks the date of the Mahabharata war, and not the start of Kali as thought so far. The actual start of Kali was 36 years later (-3102 + 36) = -3066 BC, a date which matches the astronomical Kali-Configuration very well, as shown in this article.

Misconception Summary

Indian Cosmology is composed of fascinating frameworks of time that range from the minuscule to the mind-bogglingly ginormous. All of these time-cycles, except the very largest, are based on actual astronomical data.

The Indian cycles are based on mean-motions. In popular culture, however, they are often misrepresented as true-motions, thereby implying conjunctions of actual planets. Exact-conjunctions, whether true or mean, that involve several heavenly bodies, are practically impossible.

The Kali-Epoch, like the modern Julian Date, is mainly an astronomical calculation framework, which appears to have found its way into Indian mythology over time.

No actual date for the Kali has ever been specified in any ancient text. Astronomical tradition has it that the Kali started on Feb. 18, 3102 BC. A computer study finds a much better match for Kali as of April 08, 3066 BC.

Featured Image: civilizationupgraders

To be continued…

Explore Indian Astronomy Series

This Series was first published on India Facts.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. Indic Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.