Land grab of Hindu temples is rife in Pakistan. The courts sometimes step in but in most cases the battle has already been lost. The Sri Laxmi Narain Temple in Karachi is a case in point. Abbasi mentions the takeover of a major portion of the temple land by the recreational area of Port Grand. Spread over 22,000 sq ft, the Port Grand complex now has malls, eateries and waterfront activities, on land taken grabbed from the temple. In another instance, the cantonment administration of Peshawar wanted to take over 80 Hindu homes along with the Valmiki Temple to build a shopping mall. The residents had to fight it out with the cantonment board for fifteen long years before it finally withdrew its decision.

In the interiors of Sindh, Pakistan’s internally displaced people (primarily from the restive Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province) have taken over prime temple and Dharamshalas and converted them into residences.

The people displaced from the mountains brought with them their hardline version of Islam with them, which is incompatible with the Sufi traditions of the desert. Abbasi mourns the demise of the Sufi traditions as a result of the land grab. It is however, worth noting that this happened in a province where more than 90% of Pakistan’s Hindus live and are in majority in areas like Nagarparkar, where these incidents happened.

The threat to temples in Pakistan is not limited to land grabs alone. The days following the demolition of Babri Masjid, in India, witnessed a 1,000 temples across Pakistan being burnt, demolished and looted. It is hard to imagine how events in one country might lead to reactions in another. But such incidents are not new to Pakistan. The Islamists, the State and the Army encourages violent reactions to events that are disconnected with the realities of Pakistan. Be it the reaction to the Danish cartoon incident or to Charlie Hebdo. Pakistan has always reacted violently for events that happened thousands of kilometres away. Killing and looting its own people in order to serve the identity of “Ummah”.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="598"] Hinglaj temple. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

Hinglaj temple. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

The language of the book attempts to compensate for the State apathy and the general state of despair that the Pakistani Hindus live in. The description of the temples, the people she met there and the conversations she had with them paints a picture, which seem to seek help, at times bordering on sympathy. This doesn’t come as a surprise though. There are instances in the book where we are told that the Hindu community in the country is forced to adopt a low profile. Their festivals are celebrated within the confines of their temples. The temple idols, in some cases, are locked away in strong rooms for safety. They are forced to worship broken idols, for there are no artisans to build new ones or they don’t want to build new ones because they fear they too will be desecrated. Many Hindus are forced to adopt Christian identities to escape Islamist violence, for the Islamists consider Christianity a lesser evil than Hinduism.

The instances of wanton crimes against the Hindus are so pervasive that the National Student’s Federation in Karachi had to organise a human shield to ensure the safety of Hindus celebrating Holi. Sadly such human shields can only do so much. The larger Hindu population lives in constant fear. The incidents of Hindu girls being abducted and then forcibly converted to Islam and married off can be read here, here and here. It is not that only teenage girls in far off districts of Sindh are the only ones falling prey to the organised conversions machinery of Pakistan. Hindu doctors have come under attack in the past. Read about them here and here.

The Hindus are not alone in their struggle for existence. The Sikhs too face similar challenges.

Many temples double up as Gurudwaras with images of the Sikh gurus finding place next to a Shivling or a Durga idol. The two religions coexist and share their limited resources to keep their faiths alive. Some temples are lucky to have received government grants for their renovation in the aftermath of the Babri riots. Many were destroyed beyond repair and have been taken over by the State for other purposes.

Though the Hindus of Pakistan live under constant fear or persecution and violence, they seem to have managed to keep themselves updated with the religious developments in India. Just like northern India saw a sharp increase in the number of Shirdi Sai Baba temples in the late 90s, Pakistan, especially Sindh, too has seen an increase in Sai Baba patrons. Many temples in Sindh have a small Sai Baba statue, sitting next to other deities in the temple. Indian influence is also seen in the calendar art. The pictures in the book are a testimony to the similarities in depiction of gods and goddesses. The only difference being the Pakistani temples use Urdu as a medium of communication. Pictures show arti timings, public notices, religious phrases and “Jai Mata Ki” chants written in Urdu.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="780"] Katas Raj is one of the oldest temples in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

Katas Raj is one of the oldest temples in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

Abassi highlights, what can be called, the syncretic culture of Pakistan. Many Hindu temples of Pakistan receive Muslim and Christian devotees who not only visit but also serve in the temples. They are usually people who came with a mannat and became devotees once their wish was granted. This is nothing extraordinary for an Indian. Millions of Hindus offer prayers at the mazaars and dargahs regularly. Some seek a child while others seek health and wealth. There is nothing out of the ordinary in such an act. But in Pakistan, where one might get killed for being the wrong kind of Muslim, serving and praying in a temple is definitely an act of bravery and perhaps desperation. During the interviews that Reema conducted with the caretakers and pilgrims at various temples, they tell her how their neighbours are friendly and supportive. How terrorism is only about a few people adopting violent means. But given the dire state in which the community lives, it is difficult to imagine such a situation.

Amidst all the gloom that one witnesses in the book, there are two temples that stand out. One on the shores of the Arabian Sea and the other, up north in the restive province of Punjab. Separated by more than 1,500 kilometres, these temples are the oldest in Pakistan and one of the oldest in the Indian Subcontinent.

The Hinglaj temple in Balochistan province, approximately 270 kilometres from Karachi, is one of the 52 Shakti Peeths of Hindus.

The temple is in a cave and welcomes a large number of pilgrims during Navratri. Bhandaras are organised for the devotees and celebrations are carried out throughout the night. The antiquity of the temple is such that it has been claimed by the Muslims as well. Local Balochs and pilgrims from Iran visit the temple every year, on what they call, “Nani ki Haj”. Nani being the deity. The Muslim pilgrims have weaved their own folklore and consider Hinglaj Mata to be an Islamic preacher who came to convert people to Islam and hence revere her. The Hindu legends maintain that this was the place where a part of Sati’s head fell while Shiva performed Tandav in grief, reminiscing the memories of Sati, his wife. Ram, Lakshman and Sita are believed to have visited here during their Vanvas.

Up in the north is the ancient temple of Katas Raj. Chronicled by Faxian and Xuanzang, as a seat of Buddhist learning, this place is of significant religious and historic importance. The name Katas Raj is believed to have been derived from Kataksh, i.e. tearful eyes. It is believed that it was here that Sati, immolated herself when her father Daksh disrespected Shiva. Shiva sat here with tearful eyes with the corpse of Sati and his tears formed a pool, which still exists in the temple complex. Apart from mythology, the place has been recorded by Pliny and Strabo too. Katas Raj used to be a seat of Jain learning and Alexander in all likelihood met the “ten Sophists” somewhere in the region. The Chinese travellers recount stupas and monasteries built by Ashok and many priests practicing the Hinyana sect of Buddhism. Though by the time Xuanzang visited Katas Raj the Huns had destroyed a large part of the Stupa. Later Guru Nanak is also believed to have visited the site. Baisakhi and Shivratri are the most celebrated events at the temple.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="573"] Katas Raj temple in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

Katas Raj temple in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search[/caption]

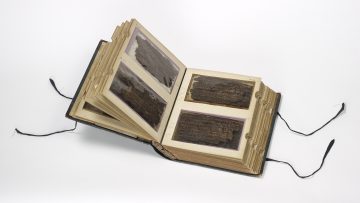

The book is full of pictures, the images of temples, deities, forts, landscape, make it an interesting read. One can see Abaasi’s words coming alive in those pictures. With few exceptions, the temples in Pakistan can easily be mistaken for a residential building. Especially the ones, which were renovated in the aftermath of Babri riots. Tiled walls, low ceilings, small and cramped garbh-grihas, make a very depressing viewing. Karachi seems to be the only place, which is more tolerant than rest of the country. Tolerance is relative and one can see that in Karachi. Struggling to keep their faith, they fight with the administration in courts to prevent the Army taking over their land. They make do with their temple ghats, by the sea being polluted with sewage from the toilets nearby. Despite all this the Hindus of Karachi can enjoy the fact that at least they are not being driven out and killed by the Islamists.

The book is a rare view into Pakistan’s Hindu lives and their struggle to keep their faith. At times the book confirms our perception of Pakistan as an intolerant state, but at times it also offers refreshing surprise. If you are someone who loves history and culture, this is the book that you should read. Not heavy on information or data but rich in imagery, Historic Temples in Pakistan is a window into the mysterious lanes and by lanes of Pakistan’s Hindu hearts.

-->The partition of India in 1947 led to the largest human migration in history. Around fifteen million people crossed the borders on both sides. Communal violence claimed many lives and millions of families lost their family members, livelihood and property for ever. The partition left a wound that is still healing and will probably leave a permanent scar on our collective memories. The primary goal for Jinnah to create Pakistan was to create a homeland for the Muslims of India. He firmly believed that Hindus and Muslims were two different nations and hence cannot coexist.

It was surprising that of the estimated 41.2 million Muslims in the dominion of India only 17.4% decided to migrate to the promised land of Pakistan, mostly from the modern states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Delhi.

A staggering 82.6% decided to stay back. The census of India, 1951 counted 9.8% of the Indian population as Muslims. Today, in a hostile country, according to Jinnah, their number has gone up to 14.2% (census 2011). In absolute terms from 34 million in 1951 to 172.2 million in 2011. The story in Pakistan however is completely different.

Pakistan today has become synonymous to international terrorism, sectarian violence and political killing fields. The strained relationship between India and Pakistan leave little room for exchange of information that is not related to terrorism or Pakistan’s covert war on India. Reema Abbasi’s book is an attempt to look into the lives and culture of Hindus in Pakistan. The 1951 census of Pakistan recorded more than 23% of its population as Hindus, most were in East Pakistan, what is now Bangladesh. Today they are reduced to a small minority, of 2% and are constantly under threat from Islamists, the Army and the State of Pakistan. They live under assumed Muslim identities to escape the targeted violence against non-Muslims.

Abbasi’s work is thoroughly backed by careful research. She chronicled the temples, the festivals and the lives of ordinary Hindus in cities, towns and villages of Pakistan. She travelled to all four provinces of the country, looking for her stories. From the desert of Thar in Sindh to the coast of Baluchistan and mountains of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, she and her photographer, Mahida Aijaz traversed the country for a year collecting stories and pictures.

The description of temples and their legends flow seamlessly from the Vedic era to the colonial chronicles, weaving a compelling narrative for the reader.

Throughout the book one finds a common thread, that of neglect and decay, which connects all the temples. Most ancient temples in Pakistan are slowly decaying for the want of funds for their upkeep. In many cases the vast estate that these temples once stood on, has been encroached by either the Army or the State for “development” activities. Army recreation facilities, restaurants, malls and schools have come up on land that once belonged to the temples.

Land grab of Hindu temples is rife in Pakistan. The courts sometimes step in but in most cases the battle has already been lost. The Sri Laxmi Narain Temple in Karachi is a case in point. Abbasi mentions the takeover of a major portion of the temple land by the recreational area of Port Grand. Spread over 22,000 sq ft, the Port Grand complex now has malls, eateries and waterfront activities, on land taken grabbed from the temple. In another instance, the cantonment administration of Peshawar wanted to take over 80 Hindu homes along with the Valmiki Temple to build a shopping mall. The residents had to fight it out with the cantonment board for fifteen long years before it finally withdrew its decision.

In the interiors of Sindh, Pakistan’s internally displaced people (primarily from the restive Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province) have taken over prime temple and Dharamshalas and converted them into residences.

The people displaced from the mountains brought with them their hardline version of Islam with them, which is incompatible with the Sufi traditions of the desert. Abbasi mourns the demise of the Sufi traditions as a result of the land grab. It is however, worth noting that this happened in a province where more than 90% of Pakistan’s Hindus live and are in majority in areas like Nagarparkar, where these incidents happened.

The threat to temples in Pakistan is not limited to land grabs alone. The days following the demolition of Babri Masjid, in India, witnessed a 1,000 temples across Pakistan being burnt, demolished and looted. It is hard to imagine how events in one country might lead to reactions in another. But such incidents are not new to Pakistan. The Islamists, the State and the Army encourages violent reactions to events that are disconnected with the realities of Pakistan. Be it the reaction to the Danish cartoon incident or to Charlie Hebdo. Pakistan has always reacted violently for events that happened thousands of kilometres away. Killing and looting its own people in order to serve the identity of “Ummah”.

Hinglaj temple. Source: Google Image Search

The language of the book attempts to compensate for the State apathy and the general state of despair that the Pakistani Hindus live in. The description of the temples, the people she met there and the conversations she had with them paints a picture, which seem to seek help, at times bordering on sympathy. This doesn’t come as a surprise though. There are instances in the book where we are told that the Hindu community in the country is forced to adopt a low profile. Their festivals are celebrated within the confines of their temples. The temple idols, in some cases, are locked away in strong rooms for safety. They are forced to worship broken idols, for there are no artisans to build new ones or they don’t want to build new ones because they fear they too will be desecrated. Many Hindus are forced to adopt Christian identities to escape Islamist violence, for the Islamists consider Christianity a lesser evil than Hinduism.

The instances of wanton crimes against the Hindus are so pervasive that the National Student’s Federation in Karachi had to organise a human shield to ensure the safety of Hindus celebrating Holi. Sadly such human shields can only do so much. The larger Hindu population lives in constant fear. The incidents of Hindu girls being abducted and then forcibly converted to Islam and married off can be read here, here and here. It is not that only teenage girls in far off districts of Sindh are the only ones falling prey to the organised conversions machinery of Pakistan. Hindu doctors have come under attack in the past. Read about them here and here.

The Hindus are not alone in their struggle for existence. The Sikhs too face similar challenges.

Many temples double up as Gurudwaras with images of the Sikh gurus finding place next to a Shivling or a Durga idol. The two religions coexist and share their limited resources to keep their faiths alive. Some temples are lucky to have received government grants for their renovation in the aftermath of the Babri riots. Many were destroyed beyond repair and have been taken over by the State for other purposes.

Though the Hindus of Pakistan live under constant fear or persecution and violence, they seem to have managed to keep themselves updated with the religious developments in India. Just like northern India saw a sharp increase in the number of Shirdi Sai Baba temples in the late 90s, Pakistan, especially Sindh, too has seen an increase in Sai Baba patrons. Many temples in Sindh have a small Sai Baba statue, sitting next to other deities in the temple. Indian influence is also seen in the calendar art. The pictures in the book are a testimony to the similarities in depiction of gods and goddesses. The only difference being the Pakistani temples use Urdu as a medium of communication. Pictures show arti timings, public notices, religious phrases and “Jai Mata Ki” chants written in Urdu.

Katas Raj is one of the oldest temples in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search

Abassi highlights, what can be called, the syncretic culture of Pakistan. Many Hindu temples of Pakistan receive Muslim and Christian devotees who not only visit but also serve in the temples. They are usually people who came with a mannat and became devotees once their wish was granted. This is nothing extraordinary for an Indian. Millions of Hindus offer prayers at the mazaars and dargahs regularly. Some seek a child while others seek health and wealth. There is nothing out of the ordinary in such an act. But in Pakistan, where one might get killed for being the wrong kind of Muslim, serving and praying in a temple is definitely an act of bravery and perhaps desperation. During the interviews that Reema conducted with the caretakers and pilgrims at various temples, they tell her how their neighbours are friendly and supportive. How terrorism is only about a few people adopting violent means. But given the dire state in which the community lives, it is difficult to imagine such a situation.

Amidst all the gloom that one witnesses in the book, there are two temples that stand out. One on the shores of the Arabian Sea and the other, up north in the restive province of Punjab. Separated by more than 1,500 kilometres, these temples are the oldest in Pakistan and one of the oldest in the Indian Subcontinent.

The Hinglaj temple in Balochistan province, approximately 270 kilometres from Karachi, is one of the 52 Shakti Peeths of Hindus.

The temple is in a cave and welcomes a large number of pilgrims during Navratri. Bhandaras are organised for the devotees and celebrations are carried out throughout the night. The antiquity of the temple is such that it has been claimed by the Muslims as well. Local Balochs and pilgrims from Iran visit the temple every year, on what they call, “Nani ki Haj”. Nani being the deity. The Muslim pilgrims have weaved their own folklore and consider Hinglaj Mata to be an Islamic preacher who came to convert people to Islam and hence revere her. The Hindu legends maintain that this was the place where a part of Sati’s head fell while Shiva performed Tandav in grief, reminiscing the memories of Sati, his wife. Ram, Lakshman and Sita are believed to have visited here during their Vanvas.

Up in the north is the ancient temple of Katas Raj. Chronicled by Faxian and Xuanzang, as a seat of Buddhist learning, this place is of significant religious and historic importance. The name Katas Raj is believed to have been derived from Kataksh, i.e. tearful eyes. It is believed that it was here that Sati, immolated herself when her father Daksh disrespected Shiva. Shiva sat here with tearful eyes with the corpse of Sati and his tears formed a pool, which still exists in the temple complex. Apart from mythology, the place has been recorded by Pliny and Strabo too. Katas Raj used to be a seat of Jain learning and Alexander in all likelihood met the “ten Sophists” somewhere in the region. The Chinese travellers recount stupas and monasteries built by Ashok and many priests practicing the Hinyana sect of Buddhism. Though by the time Xuanzang visited Katas Raj the Huns had destroyed a large part of the Stupa. Later Guru Nanak is also believed to have visited the site. Baisakhi and Shivratri are the most celebrated events at the temple.

Katas Raj temple in Pakistan. Photo by Nefer Sehgal. Source: Google Image Search

The book is full of pictures, the images of temples, deities, forts, landscape, make it an interesting read. One can see Abaasi’s words coming alive in those pictures. With few exceptions, the temples in Pakistan can easily be mistaken for a residential building. Especially the ones, which were renovated in the aftermath of Babri riots. Tiled walls, low ceilings, small and cramped garbh-grihas, make a very depressing viewing. Karachi seems to be the only place, which is more tolerant than rest of the country. Tolerance is relative and one can see that in Karachi. Struggling to keep their faith, they fight with the administration in courts to prevent the Army taking over their land. They make do with their temple ghats, by the sea being polluted with sewage from the toilets nearby. Despite all this the Hindus of Karachi can enjoy the fact that at least they are not being driven out and killed by the Islamists.

The book is a rare view into Pakistan’s Hindu lives and their struggle to keep their faith. At times the book confirms our perception of Pakistan as an intolerant state, but at times it also offers refreshing surprise. If you are someone who loves history and culture, this is the book that you should read. Not heavy on information or data but rich in imagery, Historic Temples in Pakistan is a window into the mysterious lanes and by lanes of Pakistan’s Hindu hearts.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.