This paper was first published at the conference on Indigenous environmentalism.

Abstract

Nāga worship (worship of snakes) is one of the most remarkable forms of religious practice of India. Sarpakāvu-s (sacred groves dedicated to nāga worship) play an important role in the religious and socio-cultural fabric of Kerala’s society. They are the repositories of both spiritual and biological wealth of India and the world. According to the “Comprehensive Study of Sacred Groves in Kerala” Report no. 5 on Alappuzha District conducted by Institution of Foresters Kerala in 2018, there are a total of 2,242 sacred groves which occupy 451.84 acres of land. These sacred groves have established a unique network of sustainable ecological system and brought about huge biological and ecological significance – a positive consequence of minimal human impact on natural habitat. In this paper, the sarpakāvu-s of Alappuzha district are taken as a case study to understand how spiritual beliefs help to preserve the sustainable ecological system through traditional customs and rituals.

Introduction

The original inhabitants of Bharātavarśa worshipped natural phenomena, heavenly bodies and nature in all her manifestations. They lived in perfect harmony with nature because they considered themselves as part of the nature and understood their interdependence with the vegetation, the fauna, the rivers, the hills and the mountains for their well-being and survival. Nature worship has been prominent in Vedic and Tantric traditions. Today, as humanity faces environmental disasters for reasons such as global warming and climatic change, the critical situation demands a return to our ancestors’ attitude towards nature, if not for the same reasons, for our very survival.

Nāga worship is still being practiced in many sacred groves of Kerala. It can serve as a good model of how spiritual beliefs help to preserve the sustainable ecological system through traditional customs and rituals.

Nāga Worship

As one of the most remarkable and primitive forms of religious practice, Nāga worship (worship of snakes) has been widely established with a broad variety of rituals and local customs throughout India. This age-old tradition is still prevalent in the present time with great socio-cultural and religious influences on local communities and villages.

Origin and History

I. Textual Sources

Nāga worship has been mentioned in ancient literatures, particularly in Vedas, Sutras an the epics.

The Ṛg-Veda mentions about the initial and developing stages of nāga worship and it became a regular deity for worship by Yajurvedic people (Sekhar, 2014:48). According to T. G. Sastri [Sekhar, 2014:49], the kalpasūtra-s give clear instructions on when and how the offering to nāga should be done. For example, Gṛhya-sūtra provides the specifics and procedures of the annual ritual worship called “sarpabali” for the purposes of honoring nāga and warding away evil spirits. In Pāraskara-gṛhya-sūtra, the sacrificial rites to nāga are also detailed. Āśvalāyana-sūtra mentions the sacrificial offerings for gratifying nāga.

Epics narrate a lot of stories about famous nāga-s. In particular, Ādiparva, the opening chapter of the Mahābhārata, is full of stories and myths around nāga-s in both benevolent and dreadful natures: the myth of its birth, the story of enmity between nāga and Garuda, the story of Nāga Padmanābha, etc. Other stories, such as the murder of king Parīkśit and the hostility between nāga and Pāṇḍava-s, are also illustrated in other epic literature.

II. Archaeological Evidence

The oldest pictorial evidence – the nāga sculpture belonged to 100 B.C., now being kept in State Museum, Lucknow – was discovered in the region of Mathura, the great centre of nāga worship and the home to great art schools in ancient India. This life-size figure is edged with seven-snake hood at the back of its collapsed head in the standing posture. As suggested from its particular pattern and measurement, this sculpture might have been used for worship. Another important sculpture is the seven-hooded nāga figure, accompanied by two nāgini-s on left and right sides. Underneath stands a line of four male and five female human worshippers with two children. All these anthropomorphic figures are holding one third of snake body in their left hands (Sekhar, 2014:54). There are also several inscriptions from the early centuries of Christian era which pay homage to nāga worship.

Association with Different Traditions

Nāga worship was a widespread form of worship in ancient time of India. It was commonly assimilated into other major forms of sects, predominately Śaivism and Vaiśnavism in Kerala, and it was found to come into different appearances as a result of socio-religious adaptation.

I. Śaivism

Since centuries, nāga has been most closely associated with Śiva among all deities on Hindu pantheon. The most famous one is Vāsuki, the snake king with a gem called nāgamaṇi on his head and coiling around the neck of Śiva, who blesses and wears it as an ornament. In the Mahābhārata, Śiva is depicted to wear kuṇḍala, upavīta, udarabandha, keyūra and kaṅkaṇa of snake, and also snake skin as his outer garment. Thus, he is called nāgabhūṣana – the snake adorned one.

Several sacred groves, such as in Mankonmbu in Alappuzha district, are found worshipping “nāga coiled liṅga” where Śaivite mantra-s are being chanted for propitiation of Vāsuki during pūja-s. Nāga idols are often seen along with Śivaliṅga. These living evidences show the profoundly deep connection between Śiva and nāga.

II. Vaiśnavism

Nāga is depicted as Śeśa or Adiśeśa, the king of nāga-s in Vaiśnavism. Viṣṇu is frequently depicted as resting on Śeśa, which is considered as his devoted servant with a thousand hooded-head and as the lord of pātāla. “Śeśa” means “remainder” – that which remains when all else ceases to exist. The Matsyapurāṇa mentions that when “all creatures are consumed by fire at the end of the yuga, Śeśa only will remain.” Sometimes, he is also called Ananta, meaning “endless”, as he remains in existence even when the whole universe is destroyed at the end of the kalpa. The Bhāgavata and Viṣṇu Purāna-s say, “the cosmic snake Ananta being both the source and physical support of all creation.”

III. Aṣṭanāga-s

The concept of Aṣṭanāga-s is dominant in nāga worship of central Kerala. The eight great nāga-s are Ananta, Vāsuki, Takśaka1 , Karkkodaka, Shanghupala, Gulika, Padma, and Mahāpadma. Among them, Ananta and Vāsuki are considered as the kings of nāga-s. Aṣṭanāga-s are commonly depicted in kalamezhuthu, a popular ritualistic art form during nāga festival, in the form of natural-powdered drawing with diverse artistic expressions. They are also seen in mural paintings of some temples.

Symbolic Representations of Nāga

According to mythical beliefs among various communities of Kerala, nāga-s have been given several symbolic representations and are revered for their divine powers and characteristics. Popular depictions include guardian of water, ancestor spirit, god of fertility, protector of treasures and tutelary deity.

I. Guardian of the Waters

There is a popular belief throughout India that, nāga is the guardian of water bodies and brings rain for fertilizing lands. In Kerala, especially central Kerala, nāga deities are commonly worshipped in sarpakāvu-s, sacred groves dedicated to nāga, where a pond is always attached. In Alappuzha district, nāga deities were traditionally placed along the banks of river, with the belief that they would protect the river and save people from natural disasters. During Ayilyam pūja, nērum (tender coconut) and pālum (milk) are offered to appease nāga deities. These customs indicate nāga’s strong association with water.

II. Ancestor Spirit

Nāga-s have been believed as the representative of ancestor spirits in the region. They stand for ancestors in Vedic astrology. Therefore, Hindu families in the region customarily reserves a space inside their house compounds and consecrates it as sarppakāvu, which contains a water body, a patch of forest land and deity images, for nāga worship.

III. God of Fertility

Since time immemorial, nāga deity has been worshipped as the symbol of fertility, for both human offspring and fertile land. It is popular that couple with progeny problem give offerings to nāga-related temples. For instance, childless couples perform urulikamaztha (putting of cauldron) to nāga deities in Mannāraśāla Temple in Alappuzha district of Kerala, wishing for children.

Besides, nāga-s frequently appear in Indian mythology as the prominent guardian of hidden treasures of the world kept in pātāla. Customarily nāga-s are worshipped as tutelary deities along with other major deities in houses and temples (Śaivite, Vaiśnavite or other sects) of Kerala.

Modes of Worship

There have been various rituals performed to propitiate nāga deities. According to traditional customs, women have a prominent status in nāga worship in Kerala. Therefore, almost all nāga rituals are performed by valiyamma (the elder lady) of the concerned family or Brahmin priests. Rituals conducted in sarpakāvu-s are varied depending on community beliefs. The major rituals in Kerala are briefly illustrated below:

I. Āyilyam Pūja

Being the most important ritual of nāga worship in sarpakāvu, Āyilyam-pūja is offered to the star āyilyam once a year usually on āyilyam day during month of September to October (Kanni in Malayalam calendar) which is the birthday of Vāsuki, or that of November to December (Vṛṣchikom in Malayalam calendar). Monsoon period between June and August is avoided since the rainy season is believed to be the enjoyment period of snakes. Austerity is observed seven or nine days prior to the pūja day. Accompanied by mantra chanting, the entire pūja is carried out in three steps:

1. Vigrahaśudhi (cleaning of idols): At this preparatory stage, nāga deities are initially cleaned by water, followed by oil, milk, tender coconut water and turmeric powder. Then they are beautifully adorned by garlands.

2. Pīdapūja and Mūrtipūja (worship of the pedestal of idols): priest invokes power into nāga deities through mantra recitation. Then he gives pālpāyasam (the sweet offering made of milk and rice) to each deity, to nāgarāja first and then to other deities.

3. Prasannapūja: Nōrum pālum/ nērum pālum (dough and milk) is offered to all deities by priest in the presence of agni (fire). It is made of rice flour, saffron powder, cow’s milk, tender coconut water, fruit of “kadali” plantain and ghee. The whole ritual is proceeded with some minor puja-s called Puśpānjalī and ended with ārati. It is usually followed by two major rituals, namely Nāgakalam and Pulluvanpāttu, from evening until late night.

II. Nāgakalam

Nāgakalam is a kind of kalamezhuthu dedicated to nāga deities conducted by Kuruppanmar community, particularly during āyilyam festival. Kalamezhuthu is an ancient ritualistic tradition of sacred drawings of deities with the use of powders made from natural materials of five colours. Nāgakalam is the kalam (drawing) drawn in names of different mythical nāga-s. Aṣṭanāgakalam – the drawing of the eight great nāga-s – is the mostly portrayed form, other kalam-s also include Nāgarājakalam, Nāgayakśikalam and Sarpayakśikalam, etc.

III. Pulluvanpāttu

Pulluvanpāttu is the ritualistic song singing performed by Pulluvar community, which has been keeping this old tradition since time immemorial, for worshipping nāga deities. Pulluvanpāttu is conducted around the decorated nāgakalam during āyilyam festival. This ritual is kept alive with all of its antique nature till today, elucidating different stories about nāga-s, praising Nāgarāja and his consorts, as well as explaining the details of nāga worship.

IV. Sarpabali

Namboothiri Brahmins of Kerala is a dominant community of nāga worship in the region. Their mode of worship is very different from that of other communities, and highly resembles Vedic rituals. Sarpabali is their ritualistic ceremony dedicated to aṣṭanāga-s during āyilyam festival, which is considered as the most sacred nāga pūja and is conducted only by tantric priests. During the pūja, the tantric priest invokes aṣṭanāga-s and offers food to them symbolically. It is performed for the purposes of resolving ill-effects such as sarpadōsha and sarpaśapam, as well as for removing skin diseases, increasing progeny, and maintaining the well-being of devotees, etc.

V. Theyyam

Theyyam is a ritualistic dance form performed by lower-caste communities of Northern Kerala, either in kāvu-s or temples. Theyyam-s connected to nāga worship are called Nāgatheyyangal, and they can be classified into three categories: nāgakanyā/ nāgakanni theyyam, nāgarāja theyyam and nāgakandan theyyam. During the ritual, performers dress like nāga and dance in front of devotees. Usually their head or neck portion shows nāga features. In particular, nāgakanni theyyam is usually performed for progeny. The performers of decorate themselves with coconut leaves and put a huge crown, which resembles snake hood, on their heads. Their faces are also decorated with snake-related designs.

Sacred Groves

In India, more than 50,000 sacred groves have been reported in different parts of the country. They can be seen in almost all states throughout the country, e.g. in the Himalayas, highlands of Bihar, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, etc. Many people have been customarily respecting sacred groves since these lands are believed to be the sections of the forest where spiritual beings reside. Even though forest exploitation, urbanization and change of religious beliefs, etc. have interfered their conservation, sacred groves are still a prevalent feature of balanced human-nature relationship in India.

Sacred groves can be of large or small scales. They consist of either a few trees or forests of a few acres. These groves are generally dedicated to the local deities or tree spirits or ancestral spirits, and are protected by local communities across generations through traditional rituals, and social taboos and consents. Ordinary activities which may harm the natural landscapes and resources are prohibited, for example, rules against tree felling prevail in sacred groves around India. This enables the pristine nature to be kept unspoiled.

Consequently, sacred groves are rich heritage of India, for not only playing an important role in the religious and socio-cultural fabric of the society, but also being ecosystems which perform immense ecological functions. They are the repositories of both spiritual and biological wealth of India and the world.

Scenario in South India and Kerala

I. General Overview

In South India, sacred groves still persist in many parts of the region although the importance given to them is gradually declining. There have been several studies, such as by Madhav Gadgil, Induchoodan and Unnikrishnan E., etc. on South Indian groves through direct observations, folk traditions and other literature.

As a tradition, responsibility for protecting groves and enforcing rules have been assumed by the local communities, since the grove is an integral part of village life. Diverse local cultures have different traditions, beliefs and rituals that are associated with conservation of sacred groves, yet in general, it is believed that the groves are the property of gods and ought not to be damaged in any way. Therefore, many activities are controlled in the groves as to honor and appease gods by keeping the nature as undisturbed as possible.

Sacred groves are protected from tree felling, gathering of wood, plants and leaves, plowing, planting or harvesting crops, hunting, fishing, grazing of domestic animals, and erection of ordinary dwellings, etc. For instance, the custom of prohibiting “untimely hunting, killing of wrong species of animals which may be totemic or sacred ones” is observed (Chandran and Hughes, 1997:417). Worships, offerings and sacrifices may or may not customarily occur inside. In some groves, limited intrusions are allowed in certain circumstances – the use of resources other than wood and wildlife is permitted, and medicinal plants and leaves for fodder can be gathered.

Sacred groves, which are also commonly known as kāvu-s2 , are found in almost all districts of Kerala. The first genuine report on kāvu-s of Kerala appeared in the Census report of Travancore published in 1891. 15,000 kāvu-s were reported to exist in Travancore (Ward and Conner, 1827:8). In 1998, Induchoodan and Balasubramanian published the studies which identified 364 important kāvu-s in Kerala with floristic wealth of over 722 species (Induchoodan, 1998:93).

Kāvu-s were once an essential part of every village of Kerala. In ancient time, these groves were in the hands of individual local families which treated them as family inheritance. These families were their sacred keepers. However, there is a gradual trend that many of them have failed to carry out the responsibilities and now some of the kāvu-s have been passed to local trusts, temple committees or other organizations such as Devaswam boards for management.

II. Kāvu-s Dedicated to Nāga Worship

Sarpakāvu (kāvu-s dedicated to nāga worship) was essentially adjunct to each well-to-do Nair and Namboodiri family of Kerala in the past (Kailash et al., 2001:8). Rules were customarily observed in sarpakāvu-s, for example, the purity of mind and body is needed for entering sarpakāvu-s; tree cutting, either a part or the whole, is strictly prohibited to avoid bad omens of blindness, leprosy and lack of progeny, etc. from befalling upon the concerned family.

Various types of nāga deities have been found in kāvu-s, which can be classified under

three iconographic divisions:

1. Anthropomorphic figures, such as Nāgarāja, Nāgayakshi, Nāgakanni and Nāgachāmundi

2. Theriomorphic figures, such as Paranāgam, Alnāgam, Anjilamaninagam, Kuzhināgam and Karināgam

3. Symbolic representations: Nāga deities are believed to live in consecrations like Chitrakudom in most sarpakāvu-s.

Till today, nāga worship is still an important feature of Kerala as nearly all kavu-s have images of nāga deities. Sarpakāvu-s are well maintained inside the house compounds of three communities, namely Brahmin, Nayar and Ezhavar. Other sarpakāvu-s in central Kerala known under family names are Amedamangalam Sarppakāvu, Mannāraśāla Naga Kāvu and Pambinmekkat Naga Kāvu, etc.

Scenario in Alappuzha District

I. General Overview

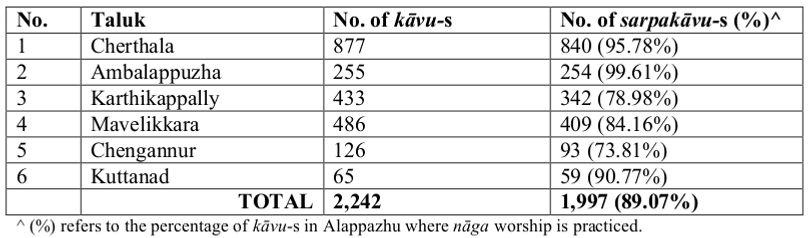

According to the “Comprehensive Study of Sacred Groves in Kerala” Report no. 5 on Alappuzha District conducted by Institution of Foresters Kerala (IFK) in 2018, there are a total of 2,242 kāvu-s which occupy 451.84 acres (182.93 ha) of land. The numbers and areas of kāvu-s in six taluks under Alappuzha are listed as below:

It is worth to note that, almost all kāvu-s in this region are still owned by individual or groups of family. Only a very few groves are managed by local trusts or Devaswam boards:

As seen above, most of the kāvu-s are still connected with ancestral homes, independent of temples and other organizations. Family members incessantly carry on the custom of lamp lighting daily in the their own kāvu-s to symbolize the collective unity of the whole family. Pujas can be conducted in monthly, seasonal or annual basis.

II. Kāvu-s Dedicated to Nāga Worship

There is an astonishing observation that, the majority of kāvu-s in Alappuzha have nāga worship:

Usually, these sarpakāvu-s do not have any particular architectural forms. Images of nāga deities are placed on stone pieces with or without carvings under a tree and are kept in the open space.

Nāgarāja, Nāgayakshiamma, Karināgam, Manināgam and Kṛṣṇa-sarpam, etc. are the nāga deities in the region. Many kāvu-s are dedicated to nāga deities alone, but it can also be worshipped in association with other deities in some cases. For instance, in Kayappurathu Kāvu of Pallipuram Village, altogether nine nāga deities are worshipped: Karinagayakshi, Karinagam, Kuzhinagam, Nagarajav, Anjanamani Nagam, Mani Nagam, Nagayakshi and Para Nagam.

In some kāvu-s, for example Nalekkatil Bhagavathy Kāvu, pūja-s are not conducted in the groves during the months of June, July and August (Midhunam, Karkidakam and Chingam) when snakes lay eggs. Therefore, human disturbance is eliminated and snake lineage can continue to grow. This is one good example of how local people in Alappuzha district still uphold the kāvu rules nowadays for spiritual and conservational purposes.

Ecological Significance of Sacred Groves

As discussed earlier, sacred groves have been safeguarded by traditional societies and indigenous communities which piously follow religious worships, socio-cultural taboos and rules. It is generally observed that these practices enable Indian society maintain an ecologically steady state with wild living resources. Even today, existing amidst human settlements and urban areas, sacred groves and associated ponds establish a unique network of sustainable ecological system and bring about huge biological and ecological significance – a positive consequence of minimal human impact on natural habitat.

I. Conservation of Biodiversity

Many sacred groves are great reservoirs of biodiversity where a diverse web of complex ecological processes can sustain continuously. Sacred groves are the homes to many valuable plant and animal species. Some studies have shown that, kāvu-s in Kerala harbor rich floral and faunal biodiversity (Kailesh et al., 2001:20). Besides, the biological spectrum of kāvu-s in Kerala highly resembles that of tropical forest. For example, there are 722 species of angiosperm in Silent Valley forest of 90 sq. km, while kāvu-s in Kerala contain 722 species in only 1.4 sq. km (Kailesh et al., 2001:21).

In the kāvu-s of Kerala, there exist an abundant amount of small mammals, primates, birds, butterflies, bats, frogs and tortoises, etc., while termites, ants and earth worms are found on the ground which are all important in enhancing soil fertility. According to KFRI Research Report [IFK Report, 2018:149], there are around 100 species of mammals, 476 of birds, 156 of reptiles, 91 of amphibians, and 196 of fishes recorded to exist in the groves of Kerala. Sacred groves enhance landscape heterogeneity and biodiversity, so to maintain the natural wholeness and integrity, as a part of the mosaic of landscape made up of forests, cultivated lands and human settlements.

II. Shelter to Threatened and Endangered Species

Due to the massive forest destruction, a variety of rare, threatened and endangered plant and animal species find their safe refuge, probably the last home, in sacred groves which are the last fragmented natural or near-natural habitats. Apart from huge trees as shelter, constant and rich availability of food and water also nurtures the breeding of birds, insects and reptiles in the groves.

IFK in its report 2018 states that a number of rare plant species can be observed in the kāvu-s of Alappuzha district: 33 rare species of trees, 16 of shrubs, 28 of climbers and 6 of herbs. In general, tree species are of the maximum number which accounts for nearly 450 species (excluding insignificant plants or very common herbs) recorded. Next comes the climber species. The dominance of wooden climbers, with frequently seen climbers among them being Dalbergiahorrida, Uvariam narum and Strychnos minor, etc., is the most notable feature of kāvu-s in the district. Extremely rare climbers can also be found there, such as Strophanthuswightianus in Onampalli Kāvu of Alappuzha. The diversity among shrubs and herbs are comparatively low. A rare species of cinnamon, Cinnamomum quilenensis, is discovered in some kāvu-s of Alappuzha. A climbing legume, Kunstleria keralensis, is reported to be found only in a kāvu of South Kerala while several rare species, such as Belpharistemma membranifolia, Buchanania lanceolata and Syzygium travuncoricum, are found only in some kāvu-s of Kerala. In addition, kāvu-s in Kerala are found to harbor a number of rare plant species, which are wild relatives of crop species, significant for improving the cultivated varieties of plants (Kailash et al., 2001:21). Besides, sacred groves are also the only surviving habitat for

several animal species.

Even though a detailed account of biodiversity of sacred groves is the immediate research that involves a long period of periodical observation by experts, at least currently we have a general picture of the precious status the groves deserve for avoiding or slowing down the process of threatened and endangered species disappearing from the planet Earth today.

III. Treasure House of Natural Medicines

Many sacred groves shelter a lot of ayurvedic, tribal and folk medicinal plants of great value for primary healthcare. For instance, medicinally important climbers can be found in the kāvu-s of Alappuzha district: Morindaumbellata, Pothosscandens, Salacia fruitcosa and Salacia chinensis, etc. (IFK Report, 2018:29). If these plants are well preserved in sacred groves, there will be a great potential of diverse medicinal and restorative use in supporting the well-being of humans and animals in the future.

IV. Watershed Protection

Since ages, village settlements have remained close proximity to sacred groves and preserve them because of watershed protection. Most sacred groves contain springs, streams, ponds, lakes or rivers which perform a significant ecological role – serve as a reliable source of water for organisms living in and around the groves. The vegetation of the grove also helps to regulate constant water supply throughout the year, by soaking up and holding water like a sponge during rain periods, and gradually releasing it during dry seasons. Flooding can be prevented during monsoons; otherwise the rainwater would have gone waste as surface-runoff, causing topsoil erosion and siltation. The occurrence and intensity of forest fire can be reduced as well. The atmospheric humidity increases as a result of the transpiration of vegetation in the groves, and this produces a more favourable climate in the nearby areas for many organisms to thrive (Kailash et al., 2001:22).

In Kerala, kāvu-s are usually associated with ponds. For example, Cherthala taluk under Alappuzha district strikingly have 90% of kāvu-s with attached ponds, in certain cases, two to three ponds (IFK Report, 2018:156).

In addition, sacred groves also serve as natural museums of giant trees, veritable gardens for botanists, gene banks of economically important species as well as endemic species and keystone species (species which have disproportionately large effect on other species in the community), and so on.

Conclusion

Sacred groves in India should be preserved and restored for many reasons, including their values as spiritual, ecological and socio-cultural. Due to weakening of traditional religious belief systems, sacred groves are facing big threats and the surviving groves are extremely reduced in number and area today. It is suggested in some studies that biodiversity in them will continue to decline.

There is an urgent need to strengthen the conservation and restoration of sacred groves for its positive functions. Indeed, it is even more important today when the planet Earth is in the devastating crisis of adverse imbalance due to over consumption of natural resources, deforestation, industrialization, pollutions and other human activities which no longer regard nature as sacred and vital to the survival of all organisms.

It is immensely important to find solutions to sustain the ecosystem inside sacred groves as much as possible. As the popular Malayalam saying regarding the protection of sacred groves cautions, “kāvutīnḍiyal kulam vaṭṭum” (“if you destroy the trees of kāvu, then ponds will dry up.”), it is essential and urgent for us to preserve sacred groves and the nature at large for the survival of ourselves and future generations.

REFERENCES

1. Chandran, M. D. Subash; Hughes, J. Donald. (1997). “The Sacred Groves of South India: Ecology, Traditional Communities and Religious Change”, in Social Compass 44(3), pp.413-427.

2. Institution of Foresters Kerala. (2018). Comprehensive Study on Sacred Groves in

Kerala Report No.5, Alappuzha District. http://www.forest.kerala.gov.in/images/pdf/scalp1.pdf

3. Jayakrishnan, N. (2015). Nagaradhanayum Thiriyuzhichilum. Thiruvananthapuram: The State Institute of Languages, Kerala.

4. Malhotra, Kailash C.; Chatterjee, Sudipto; Gokhale, Yogesh; Srivastava, Sanjeev (2001). Cultural and Ecological Dimensions of Sacred Groves in India. Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi & Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Bhopal.

5. Sekhar, Midhun C. (2014). “Nāga Worship in Central Kerala: Archeological and Ethnographical Study”, Ph.D. thesis, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.