The ancient shrine of Jagannatha at Puri is one of the sacred chatur-dhamas of India. Puri or Puruṣottama is located in the state of Odisha. Jagannatha’s influence over Odia culture is all-pervading.

The yatra to Puri is hence a very important affair throughout India and more so in the state of Odisha. Purāṇa and Sthala-Purāṇa s (both in Sanskrit and Odia) such as the Kapiḷ a Saṃhitā , Skanda Purāṇa, and others mention the method of undertaking the yatra in detail.

The paper will highlight the importance of the Puruṣottama Yatra and the diverse reflections of this yatra, including those in traditional food, the artform Pattachitra, Odissi music, Odissi dance, and typical beḍhābulā literature. Historical perspectives & accounts of yatris will be observed.

From renowned philosopher-seers who flourished centuries ago to common persons in hinterlands today, the yatra to Puri continues, albeit in different ways. In Puri, the pilgrim is not the only one doing the yatra; the deity himself has his own yatra. The juxtaposition of these yatras makes Puri a very special case to observe and ponder upon. This paper attempts to shed light on the aforesaid aspects of the centuries-old yatra to Jagannatha Puri.

Odisha and the Four Major Khetras

The eastern state of Odisha has been known by many names in the past, including Oḍra, Oḍḍīyāna, Utkaḷa, Kaḷiṅga and more. The state is replete with several hundreds of ancient Hindu temples, of which the existing structures mostly belong to the period between the 7th and 15th centuries.

Many of these temples are referred to in the Puranas or Samhitas and are linked with certain divine events in Hindu belief. Many others may not find mention in the scriptures but are held in high esteem in regional legends.

The Mādaḷ ā Pāñji, the ancient chronicle of the Jagannatha temple provides an exhaustive list of temples across the villages of Odisha along with their maintenance costs. However, it indeed makes separate mention of a few places. According to the Madala Panji, the four major sites of veneration or khetras (Skt. kṣetra) in ancient Odisha are :

A local legend recounts how Vishnu dropped his four ayudhas in Odisha. The places where the attributes fell came to be known as famous shrines.

In accordance with tradition, it is thus believed that the khetras of Puri, Bhubaneswar, Jajapura, and Konarka are shaped like the śankha, chakra, gadā, and padma respectively. The boundaries of each khetra are elaborately described in their sthala-puranas.

Puruṣottama Khetra

Present-day Puri had a significant number of names, including Puruṣottama Khetra , Śankha Khetra, Śrikhetra, Nīlāchala, Nīlādri, Kambu Kaṭaka, Daśābatara Khetra, Bhauma Khetra and more.

The importance of this shrine has been acknowledged in a wide number of scriptures, some of which are the Skanda Purāṇa, Viṣṇu Purāṇa, Kālikā Purāṇa, Brahma Purāṇa, Nāradiya Purāṇa, Matsya Purāṇa, Rudra Yāmala, Kapi ḷ a Saṃhitā and Mahābhārata. The Utkala Khanda of Skanda Purāṇa narrates thus:

pṛthivyām yāni tirthāni gagane ca tripiṣṭape

sārddha trikoti sankhyāni swargamokṣa pradāni vai /

teṣāmayaṃ tirtharājaḥ kirttitaḥ puruṣottamaḥ

sarveṣāṃ muktikṣterāṇāmidaṃ sāyujyadaṃ matam / (4.20-21)

All the Tirthas together on the earth, in the firmament and in heaven are three and a half crores in number. They bestow heavenly pleasures and liberation. This holy spot Puruṣottama is glorified as the King of all those tirthas. Among all the sacred places that bestow salvation, this one is considered to be the one which bestows (liberation called) Sayujya. [3]

Several important acharyas and seers have visited Puri, including Adi Shankaracharya, Nimbarka, Ramanujacharya, Vallabhacharya, Guru Nanak, Tulsidas, Kabir, and Chaitanya.

Adi Shankaracharya established four cardinal mathas at four corners of India. Of these, the Govardhana Maṭha is situated at Puri. The eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, including the states of Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, West Bengal, Bangaldesh, Nepal, Bhutan is under this matha.

Puri is thus considered one of the chātur-dhāmas that every Hindu desire to visit at least once in their lifetime. The pilgrimage or yatra to this shrine was hence considered extraordinary.

Expressions in Regional Culture: Odia Literature & Odissi Music

Odia literature, starting from the 14th century until the 19th century is replete with musical poems. Most of the literature composed during this period tend to be inextricably associated with music. Even simpler poetic structures, like the nabakhyari are meant to be recited in a musical way, never read without any swaras.

The ancient classical music tradition of Odisha is known as Odissi Music. Mentioned in the Nāṭya Śāstra as the Uḍra-Māgadhi Pravṛtti , this is a distinct style of ‘art music’ with its own śāstras (music treatises), rāga-tāḷ as (melodies and rhythms), prabandhas (song-repertoire), style of rendition and tradition.

Important musician-poets of this tradition include the Vajrayana Buddhist Mahāsiddhas, Jayadeba (the author of the Gīta Gobinda, born in the village Kendubilwa of the Puri district), Dinakṛuṣṇa Dāsa, Kabi Samrāta Upendra Bhañja, Banamāḷ ī Dāsa, Kabisūrjya Baḷ adeba Ratha, Rāmakṛuṣṇa Kabichandra Paṭṭanāyaka, Kabi Kaḷ ahansa Gopāḷ akṛuṣṇa Paṭṭanāyaka, and many others.

A wealth of Odia literature is about the yatra to Puruṣottama . These writings can be classified broadly into three categories: those expressing a devotee’s yearning to visit the shrine, pilgrim songs that narrate the journey to the site and guide-songs to help the pilgrim in his yatra.

The Yearning to Visit

A genre of Odia literature is known as the chautiśā (henceforth simply chautisa). This form gained much popularity as early as the 14th century and the oldest examples of it can be traced back to as early as the tenth century. Classified as a panchaḷ i as per music treatises , a [4] chautisa has 34 stanzas for the 34 consonants of the Odia alphabet from ka-khya.

Hundreds of chautisas were written, and more continue to be written even today. We find a wide variety in their subject matter, spanning the devotional (bhakti), erotic (srungāra), philosophical & esoteric (tattwa), legendary & historical (itihāsa), humorous (hāsya) and prophetic (bhabiṣya-mā ḷ ikā).

A significant number of these chautisas talk about a devotee’s ambition to undertake the yatra. The 16th-century poet Dinakrusna Dasa writes in his Gunḍichā-Bhābanā Chautisa :

kaha kaha āhe sanghāta sate hen jibanare āmbhe thibā

koṭi-brahmāṇḍa-nāthara śri-gunḍichā jātrā utsaba dekhibā se

Friend, will we be fortunate enough to behold the Gunḍichā Jātrā (another name of the Ratha Jatra) of the lord of crore worlds?

In another one called the Snāna-Smaraṇa Chautisa , he talks about the Snāna Jātra, another of Jagannatha’s major festivals :

kahe dinakṛuṣṇa śuna re sanghāta dhika heu mo jibana

koṭi-brahmāṇḍa-nātha snāna-utsaba kali nāhi darasana

keun abhāgya mora / kalā se sukha bihi antara

Friend, what use is my life if I fail to get a sight of Jagannatha’s Snana Jatra? What misfortune isolates me from that joy?

The poet goes on to reminisce about the wonderful events that he might miss, including detailed descriptions of how the deities are brought for the Jatra and other ritual proceedings. He also repeats that life is wasted without beholding these events and that his eyes fill with tears on imagining them. The importance of a yatra for a devotee can be well ascertained from these lines.

The poet Biṣṇu Dasa thrived in the last half of the 16th century. He was in the court of the king Raghunatha Harichandana of Banapur. Sachidananda Mishra has published the Khetrabiraha Chautisa of Bisnu Dasa and in his comment on the poem presents an interesting opinion.

The poet mentions his memories of the kaḷ pabaṭa within the compound of the Jagannatha temple in the 29th stanza. According to Mishra, Bisnu Dasa would have left Puri with his friends before 1568, because in that year the iconoclast Kalapahada destroyed the sacred tree.

King Ramachandra Deba of Khordha’s Bhoi dynasty restarted the Ratha Jatra in 1591. The reinstitution of this grand ritual after Kalapahada’s attacks might well have stirred Bisnu Dasa’s longing to return to Puri. In this regard, the poem presents a peculiar case worth studying closely.

The poet here is a person who has already visited the shrine but has been separated due to circumstances; hence his use of the word biraha. Thus, he remembers simpler events during his stay, like the sound of instruments, the whiff of camphor and sandalwood, the sight of Jagannatha, the crowds while pulling the chariot, the shade of the kalpabata tree and the taste of the delicious mahaprasāda.

The Route to Puri

Another kind of a poem is a boli. Usually set to simpler melodies than the more demanding chautisa, the core of a boli lies in its daily-life conversational tone. As such, bolis tend to be

extremely popular among multiple societies because of their concise, straightforward expression.

The Aṭharana ḷ ā Boli provides a unique, realistic depiction of a regular family visiting Puri during the Ratha Jatra. In it, a kid asks a motherly figure if she has pulled the chariot. The elderly woman says she has no energy left in her body to struggle in the crowds anymore; so she has kept away.

The ladies of the family look through the market delightfully and decide to buy festive delicacies like the poḍapiṭhā and chhenā khaṇḍi . Another one pleads for a drop of water and food because she cannot bear the hot sun. Her friend, unmoved by the sun, keeps looking at Jagannatha’s round eyes.

Meanwhile, a young couple is worried, for it is not possible to walk through the crowds with their child. They are relieved to find a paṇḍā servitor who agrees to keep the child for a while. Another newly-wed woman whispers into her friend’s ear that she has lost her necklace.

She is afraid of her mother-in-law, who had warned her not to wear ornaments in the fair. It is this kind of an intimate portrayal that distinguishes the Atharanala Boli. An iconic traditional song, written by Sāriā Bhika goes thus:

thakā mana chāla jibā, chakā-nayana dekhibā

śankhanābhi maṇḍa ḷ are beni netra pakhaḷ ibā / refrain /

bāṭa re bāṭa manga ḷ ā, dekhibā aṭhara-naḷā

pancha mana eka meḷ ā, narendre snāna karibā /

pahanchiba baḍadāṇḍe, se reṇu pāiba tunḍe

chhatā taḷ e rahi daṇḍe, sādhunka sebā karibā /

singhadware bhiḍābhiḍi, bāju achi beta-bāḍi

ṭhelidei jibā māḍi, dhakkā bājile sahibā /

Translation :

O worn-out mind, let us go

and behold the round-eyed one

at the core of the Sankha Khetra

to cleanse our mortal eyes.

On our way, we shall come across

the goddess Bāṭā Mangaḷā

the Aṭharanaḷā

and then we take a dip in the holy Narendra.

Then we shall reach Baḍadāṇḍa

putting that dust on our lips

we shall serve sadhus.

Finally the Singhadwāra

the beta-bāḍi

rushing with the crowd

we shall bear if someone pushes us.

This song is written entirely in a collective sense. It would not be far-fetched to imagine a group of pilgrims singing such a song to boost their spirits while traveling. Certain words need some explanation. Jagannatha is referred to as chakā-nayana, literally ‘cartwheel-eyed’ because of his circular eyes.

The goddess Bata Mangala is one of the major landmarks on the way to Puri. Bata in Odia refers to route; the goddess is called so because she is on the route and every pilgrim has to pass by her temple before reaching Jagannatha. The Atharanala is a very early bridge (originally started in the 13th century) over the Musa River.

Narendra Puskarini is one of the five major waterbodies or tirthas in the town of Puri. The wide road in front of the Puri temple is referred to as the Badadanda. Since Jagannatha himself travels on this road every year during the Ratha Jatra, even the dust is considered priceless.

Singhadwara is the main, eastern entrance of the Jagannatha temple, named so because of the two huge stone lions on either side. The beta-badi is a stick lightly tapped on a pilgrim’s head by a specific group of servitors. This is believed to be rid of one of misfortune and probably derives from Tantric rituals. The crowd in the Puri temple is seen as a part of the experience itself.

The 19th-century Kṛuṣṇali ḷ ā poet Gauracharana Adhikari writes of the joy of a pilgrim when he first spots the temple flag :

niḷ achakre ho, dekha uḍuchi banā

patitapābana nāmaṭi jāra nā /

Look, friend, look how the flag flutters on top of Nilachakra

This is very Patitapabāna.

The gigantic wheel on top of the Puri temple is called the Nilachakra. The flag on top of it is called Patitapābana Bānā. The word Patitapabana means redeemer of the downtrodden and is also the name of Jagannatha. Both the flag and the chakra are seen as identical with the deity.

The flag used to be much larger before the last few decades and could be seen from a significant distance. The area surrounding Puri was often referred to as Panchukośi, a radius of five kosas or ten miles with the temple at the center. Once the Nilachakra and Patitapabana Bana were within view, it was understood that one had entered this zone and neared the destination. After several weeks of travel, this was a moment of great joy for the pilgrim.

Interestingly, songs can be found for almost every situation one would encounter during a pilgrimage. After Chaitanya’s arrival in Odisha, kirtana became very popular. Pilgrims would often come across traveling kirtana bands on their way.

Kirtana troupes were often the first ones to encourage people to undertake the journey, instilling in them the desire by describing the wonders of the destination. They often led several first-time visitors, guiding and navigating them through difficult routes. Music was hence an instrument to motivate and inspire tired travelers to resume their journey.

The ways within Puri: Sacred Paths for Circumambulation

Once the pilgrim had reached the destination, the Puri temple presented a staggering number of shrines within its huge compound. Traditional belief advises the pilgrims to visit all these temples in a specific manner. This is known as beḍhā parikramā, circumambulating the central shrine.

A huge number of beḍhābulā songs have been written to guide pilgrims about the manner in which they should move inside the complex. One of the earliest bedhabula songs has the name of Balarāma Dāsa.

The most popular poet bearing this name was the eldest of the 15th-century panchasakhā (five friends) who spearheaded an evolution of erstwhile Odia philosophy, religion, and society.

The poem mentions the shrines starting from the left and going clockwise around the main temple: entering the Singhadwāra, Kāśī Biswanātha on the steps, Bhogamaṇḍapa, Ajāṇanātha, Bighne śwara, Baṭakṛuṣṇa, Baṭamanga ḷ ā, Anantaśayana, Khetrapāḷa, Nṛusinghanātha, Biprasabhā, Rohiṇi Kuṇḍa, Bima ḷ ā, Nanda-Jaśodā, Hanumāna, Pāduka Kuṇḍa, Āditya, Pātā ḷ eśwara, Uttarāyaṇī, Śītaḷ ā, Rudra, Pādapadma, etc.

Then the poet mentions his account of entering the main sanctum, where fabulous murals of Kānchi Bijaya have been depicted. Standing near the Garuda Stambha, he describes the golden sanctum sanctorum, the garlands of Tulasi, the whiff of sandalwood, and the Gajapati Pratāparudra serving the deities.

Another very popular such poem is by one Dina Rāmachandra. In this poem, after their conquest of Lanka, Rāma is showing Sita around the Puri temple. He takes her through individual shrines and tells them legends. Mentioned in order are Patitapābani, Nārayaṇi, Kaḷ pabaṭa, Baṭakruṣṇa, Baṭa Gajānana, Baṭa Manga ḷ ā, Bateśwara, Mārkanḍe śwara, Hari Sahadeba, Hanumāna, Bārabhāi Mahābiri, Khetrapāḷ a, Anantaśayana, Kuttāma Chandī, Muktimaṇḍapa, Mājaṇā Maṇḍapa, Ka ḷ ijuga Bheṇḍā, Nṛusingha, Bāmana, Ekāda śī Mahāprabhu, Dhabaḷ a Nṛusingha, Rohiṇi Kuṇḍa, Kāka-Bhuṣaṇḍī, Bimalā, Baga ḷ ā-Kālī-Chāmuṇda, Rādhākṛusṇa, Nanda-Ja śodā, Bhaṇda Gaṇesa, Rādhākanta, Hanumāna, Setubandha Rāmeśwara, Labaṇikhiā Gopā ḷa, Bhubaneśwari, Saraswati, Ṣaṣṭhi, Beḍhākā ḷ ikā, Mahālakhmī, Pāduka Kuṇḍa, Surjya, Loke śwara, Aisānyeśwara, Uttarāni, Śitalā, Koili Baikuṇṭha, Nī ḷ amādhaba, Jameśwara, Nīḷ akantha, Ajāṇanātha, Bighne śwara, Mrutyunjaya and more.

This poem has much more value than a mere list because of its narration of the associated legends. For example, the Ganesha image said to have been brought from Kanchi after the Gajapati’s conquest of the place is known as Bhaṇḍa Gane śa.

The word ‘Bhaṇḍa’ is used for someone who is pretentious or deceitful. The connotation here might be referring to the Tantric ucchiṣṭa pose in which this Ganesha has been depicted, with his trunk at his shakti’s yoni.

The large Varaha image placed as the parswadebatā to Jagannatha’s temple is referred to as Kaḷ-ijuga-Bheṇḍā. In traditional iconography, Bhudevi is depicted sitting on Varaha’s upraised arm. The gadā is depicted anthropomorphically as gadā-Devi, whose hand Varaha holds.

Unaware of so many iconographical nuances, the general public created their own explanation; that this god personifies an arrogant modern-day person who carries his wife on his head, but drags his old mother. So they named him ‘a lad of kali yuga’.

The Aruna Stambha has been mentioned outside the Singhadwara. This pillar was originally part of the Sun temple of Konarka and was shifted to Puri by the Marathas. Its coexistence with Rama and Sita is rather anachronistic.

Upendra Bhanja and Kabisurjya Baladeba have also in the first song of many of their epic-poems (kābyas) elaborately described the temple-complex of Puri. Most of the other ancient Jagannatha temples in Odisha seem to be built with Puri in mind. As we shall see, this literature describing the temple-plan proved to be invaluable for artists who would go on to paint the scene rather frequently.

Souvenirs for visitors: Jatri Pati and Nirmalya

Art-historian J. P. Das writes in his book Puri Paintings :

“It is said that a pilgrimage to Puri was incomplete unless the pilgrim took back with him five patas of Jagannatha, five beads, five cane sticks, and nirmalya.”

Due to the huge numbers of pilgrims to Puri, over time, a specific kind of painting developed to cater to the needs of the visitors. This type of painting is known as the jātri paṭi, literally ‘visitor painting’.

These were made by Puri’s traditional chitrakaras according to the tenets of Odisha’s Paṭachitra tradition (also why they are called patis, used in the sense of cloth-paintings) and pilgrims would buy them as souvenirs, as a warm memory of their pilgrimage and an auspicious object of veneration.

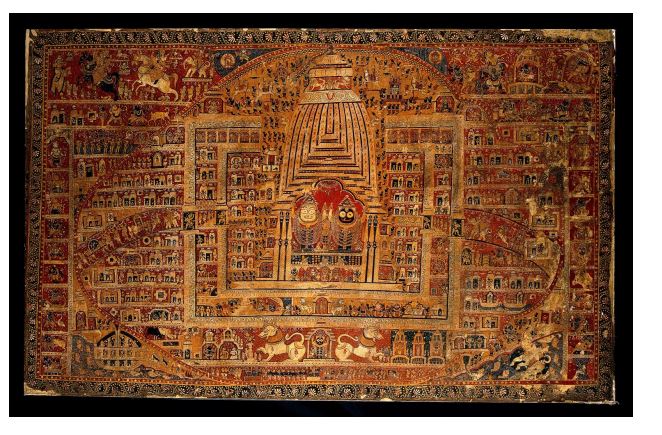

A typical jatri pati depicts the complex of the Jagannatha temple in a simplistic manner; a huge central shrine within which the three deities sit, the figures of Brahma and Shiva on either side, the ten avatars of Vishnu and a few other minor shrines. It is best explained as a flattened top-view map, so to say, since the Pattachitra style at no point employs the concepts of perspective or three dimensions.

The jatri patis were available in a wide variety, a customized version to appeal to every kind of customer. This included multiple shapes (round, square, betel-leaf shaped, scroll) and sizes (from finger-ring sized to as large as an entire wall).

The smallest jatri patis might be abstracted too much simpler layouts and made with quicker, thicker strokes. One must remember that for a huge number of buyers the paintings served a ritual function and not that of a piece of art. The cheaper jatri patis provided people an opportunity to fulfill their ritual obligations within financial constraints.

At the same time, richer patrons could afford intricately-crafted pieces. The more elaborate versions had distinctive names. One such was the Śankhanābhi Paṭi, an expanded version of the map concept. Every minor shrine within the complex of the Jagannatha temple was depicted with delicate strokes.

The bounds of Purusottama are traditionally imagined in the shape of a conch-shell, hence lending it the name Sankha Khetra. In the center of the conch-like kshetra resided the deities. This is how the name Sankha-nabhi Pati is derived.

As such, these were undertaken only by the senior-most painters of the workshop. Sankhanabhi Patis is often a veritable treasure of Odisha’s traditional iconography since each deity is depicted in a specific color and with their specific attributes, in most cases based on a dhyāna-sloka that the artist uses to imagine the deity’s form in accordance with ritual texts.

T N Mukharji mentions that around the time of his writing, the 1880s, “a long roll of painting, shewing the temple of Jagannath and the ceremonies performed therein, is sold for Rs. 40 or about £3.”

This appears to be a description of a Sankhanabhi Pati, although Mukharji does not seem to have a high opinion, even calling them ‘very rude oil-paintings’. [5]

Nonetheless, the temple-plan concept can be found as early as the 17th century, an exceptional example being a mural on the exterior walls of the Birañchi Nārāyaṇa Matha of Buguda, Ganjam. The artist depicts several festivals of the temple, including Ratha, Snāna, Jhulaṇa, and Doḷ a. Several other interesting details can be observed, such as black bucks running along the beach and a suāra servitor cooking food inside the kitchens.

Dried rice from the temple kitchen has been traditionally sold in small pink cloth packets. This is known as Nirmālya. A common souvenir, it is believed to bestow good fortune and Jagannatha’s blessing.

The staple Puri khajā, among other dry items of the Mahaprasada is often preferred by pilgrims due to its long life. These are known as sukhili bhoga and are sold in small boxes made of dried palm leaf.

Taxes and Family Paṇḍās:

Most travelers used the Jagannātha Sadak, a historic route connecting Calcutta and Puri. There were a number of Dharamsala, temples, bridges, wells, and ghats along the route, providing almost any amenity a pilgrim could ask for.

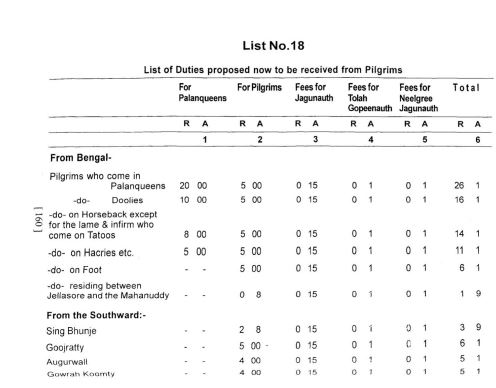

One very important aspect was the pilgrim tax. This was an idea unknown to the people of Odisha until the Mohammedans conquered the land and imposed tax as a condition for tolerating worship. W. W. Hunter remarks that the amount collected could be as much as nine lakhs of sicca rupee. The Marathas who succeeded would continue the tax on economic grounds. The British however first decided to suspend the collection of tax.

When beneficiaries including servitors of the temple complained, a systematic study was undertaken to decide an organized scheme under which tax would be charged. This would be done ‘with every degree of mildness, humanity, and care.’

A detailed report regarding establishments and customs of the Jagannatha temple was prepared by Charles Grome, collector of the Southern Division in Puri. Grome gave his report on 10 June 1805. His main informer was Jagannatha Rajaguru since he himself could not enter the temple being a non-Hindu. Grome mentions his findings regarding pilgrim tax :

The Custom of the former Government in collecting [tax form] the Pilgrims appears not to have been established on any fixed principles tho’ for the sake of form certain rates appear to have been made but never adhered to. The Collections from Pilgrims coming from Northward began at a place called Khoonta on the borders of the Morebhung [Mayurbhanj] country and continued up to the Autaranulla [Atharanala] or the entrance of the town of Poorshootum [Purusottama].

The persons exempted from duties included Sathoas who encouraged people from all over the country to visit Puri, Patadharis who brought silken ropes for the deity, Musicians & Singers, Dandi Sannyasis, Mathadharis or officials of important Mathas and Beparis or small businessman. A list of Grome’s revised proposal has been given below.

Most families spent their time with a designated family paṇḍā. Many of these pandas maintain records in which several generations of their clients are mentioned. These books are called jātri pānji. A rigorous process of documentation was followed and pandas typically knew ahead of every pilgrim’s visit.

This was supposed to ensure a good darsana. Agents of the pandas, called Gumāstas, would guide the pilgrim first until the outskirts of the town, then until the temple, and finally, take them to the sanctum sanctorum. Several people continue to perform rituals like srāddha with their family panda; this is because their records maintain the genealogy of up to seven generations.

In the end, there is a question worth making: is a yatra merely a physical journey? Traditional accounts reveal a much more holistic view of the concept of the yatra, where it is seen as a way of expanding the mind.

The pilgrim’s yatra is facilitated by an environment consisting of subtler aspects like the visual and performing arts. The sensory feedback forms as important a part of the entire experience as anything else. The yatra thus sustains an entire ecosystem of people apart from the pilgrims themselves.

Bibliography

- Das, J. P., 1982, Puri Paintings, USA: Humanities Press.

- Dash, Gaganendra Nath in collaboration with Das, Ranjan Kumar (editors), 2010, Jagannatha and the Gajapati Kings of Orissa: A Compendium of Late Medieval Texts (Rajabhog, Sevakarmani, Deshakhanja, and Other Minor Texts), Delhi: Manohar.

- Dash, Pt. Suryanarayan, 1966, Jagannatha Mandira O Jagannatha Tattwa (Odia), Cuttack: Friends Publishers.

- Dhir, Anil, Rediscovering the Jagannatha Sadak in Odisha Review, November 2015.

- Fischer, Eberhard and Pathy, Dinanath, 2012, In the Absence of Jagannatha: The Anasara Paintings Replacing the Jagannatha Icon in Puri and South Orissa (India), Zurich, Museum Rietberg: Artibus Asiae and Delhi: Niyogi Books.

- Grome, Charles, 1805, Report on the Temple of Jagernath. Edited by Prof. K. S. Behera, Dr. H. S. Patnaik, Dr. M. P. Dash, and R. K. Mishra. Bhubaneswar: Odisha State Archives, Department of Culture, Government of Odisha.

- Mukharji, T.N., 1888, Art Manufactures of India, Calcutta.

- Pani, Jiwan, 2004, Back to the Roots: Essays on Performing Arts of India, Delhi: Manohar.

- Parhi, Dr. Kirtan Narayan, 2017, The Classicality of Odisha Music, Maxcurious Publications. – Pathy, Dinanath, 2001, Essence of Orissan Paintings, Delhi: Harman.

- Pathy, Dinanath, 1990, Traditional Paintings of Orissa, Bhubaneswar: Working Artists Association of Orissa.

Primary texts (Odia & Sanskrit)

- Atharanaḷ ā Boli. Edited by Suresh Chandra Jena, 1988, Orissan Oriental Text Series (Oriya) 34: Oḍiā Boli (Volume II), Bhubaneswar: Directorate of Culture, Orissa, pp. 1-3.

- Beḍhābulā of Rāmachandra. Printed by A. C. Chakraverty, 1925, Puri.

- Beḍhābulā of Rāmachandra and Beḍhā Parikramā of Balarāma Dāsa. 1933, Cuttack : Odisha Kohenoor Press.

- Gauracharaṇa Gītāba ḷ ī, an anthology of the songs of Gauracharaṇa Adhikārī. Compiled by Babaji Baisnaba Charana Dasa and edited by Bichhanda Charan Patnaik, 1951, Cuttack: Kalinga Bharati.

- Kapiḷ a Saṃhitā, Text with an English translation and critical study. 2005, Edited by Pramila Mishra, New Bharatiya Book Corporation.

- Khetra Biraha Chautiśā of Bisṇu Dāsa. Edited by Sachidananda Misra, 1971, Chautiśā Bichitrā, Bhubaneswar: Odisha Sahitya Akademi, pp. 52-58.

- Khetra Mahātmya of Mahāraja Jaya Singha. Edited by Nilakantha Kabiraja and published by Chintamani Mishra Sharmma, 1904, Dharakote : Kesari Press.

- Mādaḷ ā Pāñji. Edited by Dr. Artaballabh Mohanty, 1932, Cuttack: Prachi Samiti.

- Oḍiā Bhajana, an anthology of ancient bhajanas in three parts. Edited by Nilamani Mishra, 1974. Orissan Oriental Text Series (Oriya), Bhubaneswar: Directorate of Culture, Orissa.

- Skanda Purāṇa in 23 volumes, Dr. G. V. Tagare, Motilal Banarsidass.

- Snāna-Smaraṇa Chautiśa and Gunḍichā-Bhābana Chautiśā of Dinakṛuṣṇa Dāsa. Edited & compiled by Bichhanda Charan Patnaik, 1931, Prachī Granthamālā – 30 : Chautiśā Madhuchakra (Dwitiya Khaṇḍa) , Cuttack : Prachi Samiti, pp. 34-52.

- Nīḷ ādrimahodayaḥ . Published by Maharaja Sri Biramitrodaya Singhadeba, Sonepur State, Odisha, 1922. Printed by V. Kar, Cuttack: The Utkal Sahitya Press.

(This paper was presented by Prateek Pattanaik at Indic Yatra conference)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.