Abstract

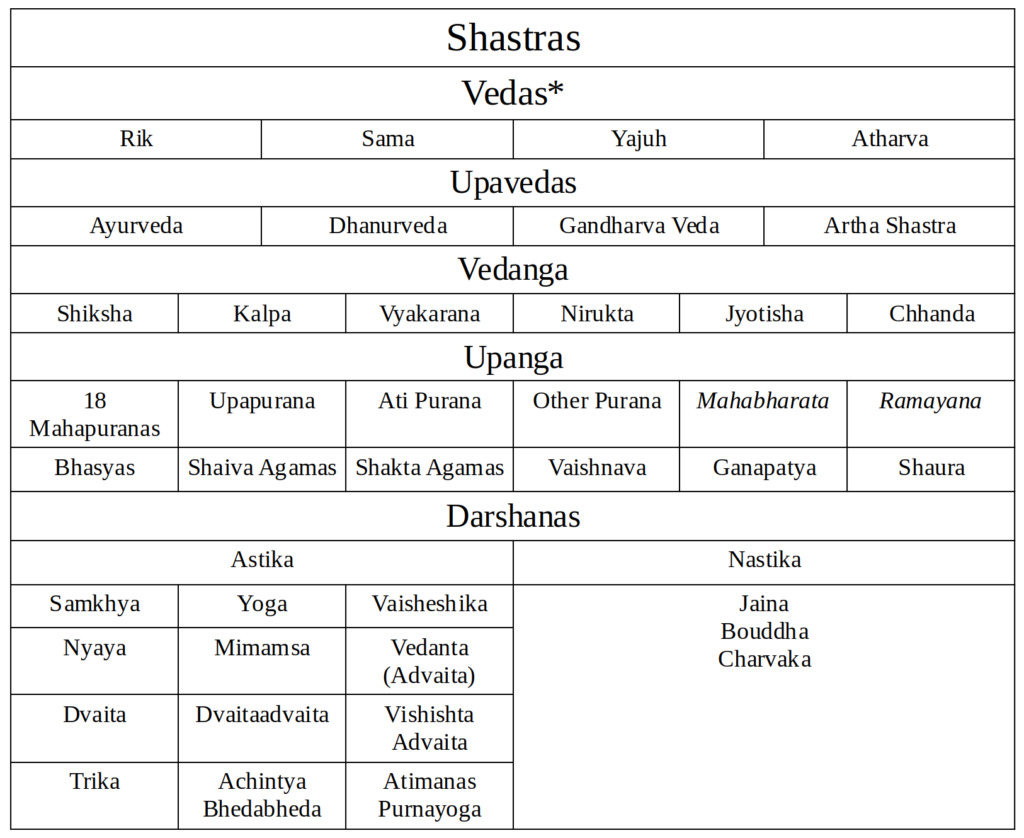

The Purāṇas and Itihasas are a vast body of extant literary works of Hindu or Bharatiya heritage. They form part of the Smruti traditions. The bulk of them are in the form of stories, epics and legends, though there are several variations.

The paper researches threefold aspects- Ādhibhautika, Ādhidaivika and Ādhyātmika, of the vast corpus. Firstly, in the bhautika world the various data present in the works can be used to reconstruct human history, understand socio-economic and political conditions, and even geographical changes over centuries and millennia. These findings are critical primarily from a community or a nation’s standpoint. Secondly, Purāṇas and Itihasas contain metaphysical knowledge beyond the gross material world or Bhautika jagata. It opens our horizons to subtler forms of energies, deva-s, and loka-s (worlds) in this universe and beyond. The stories encapsulate this knowledge and hands it down generations, safely. Thirdly, the Puranic stories are allegories that contain spiritual insights or ādhyātmika jñāna of Upaniṣadas. The complex and deep ideas are spread among masses through these scholarly works. But these symbolisms can be decoded by a yoga and/or jñāna practitioner and used for realizing the Absolute Consciousness. Thus labeling these stories as myths and mere fables and therefore untruth and false is unwarranted.

*Each Vedas are further subdivided into Saṃhitā, Brāhmaṇa, Āraṇyaka and Upaniṣada.

Ādhibhautika Insights

Today in academics it is propagated that Vedic civilization began around 1500 BCE in the Ganga-Yamuna doab. The civilization was brought to the Indian subcontinent by the so called Aryans from the steppes in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This Vedic civilization was preceded by a distinct and separate Indus Valley civilization which ended in 2000 BCE. The end of the latter is attributed to the infamous Aryan Invasion/Migration theory.

- This theory served as intellectual basis of European supremacy and british colonization in 19thcentury

- Later, it worked as a tool for breaking India forces to create racial tensions between mythical Aryan versus indigenous Dravidian people, linguistic rivalries between Tamil and Sanskrit, and disharmony between tribals (Janajatis) and people of plains (Jatis).

- Further, these timelines supported the Euro centric biases and stripped the Bharata of any independent native civilizations prior to them.

While there are numerous archeological, genetic, palaeochannel, sea level fluctuations, archaeo-botanical evidences to disprove the above time periods, the evidences from Ramayana, Mahabharata and various Purāṇas must be used to reconstruct Indian history since antiquity.

Let us see historical evidences from Itihasas and Purāṇas of a continuing civilization contained in them.

The Ramayana

As per Bhatnagar,2011 the astronomical dates mentioned in Valmiki Ramayana are around 5100 BCE.

“Valmiki in Bal Kaand, Sarga 18,Shloka 8 & 9 (1/18/8,9) has given the location of planets and stars on the date of birth of Lord Ram, which can be interpreted as follows :

- Sun in Aries

- Saturn in Libra

- Jupiter in Cancer

- Venus in Pisces

- Mars in Capricorn

- Lunar month of Chaitra

- Moon near Punarvasu

All these configurations as seen from Ayodhya match only with the sky view of one date i.e. 10th January 5114 BC, which also happened to be the lunar date of Navami of Shukla Paksha of Chaitra month, the date on which we all celebrate Ram Navami. These planetary configurations were not seen on any other date earlier than 5114 BC.

The sky views on several other dates right from the start of Putra Kameshthi Yajna (15th January, 5115 BC) to start of journey to Lanka (Uttara Phalguni Nakshtra on 19th September 5076 BC) matched exactly the descriptions in Ramayana and that also sequentially. The Sky view depicted in Ayodhya Kaand (2/4/18) was seen on the 5th January, 5089 BC when Ram was 25 years old and he had left Ayodhya for van-gaman.”

The Mahabharata

Pandit Kota Venkatchelam has researched that “According to the evidence available in our epics and Purāṇas, the date of the Mahabharata war is 36 years before Kali era. … So reckoning on the Christian era, the date of the Mahabharata war works out to 3138 B.C.”

Apart from references from Purāṇas and Mahabharata, he has substantiated his Mahabharata and Kali era(3102 BCE) findings with genealogies from Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, accounts of Nepal, continuous Puranic genealogies of Magadha kings till Chandragupta Maurya, Varahamihira’s Brihatsamhita, annual calendars (Panchhangas) and inscriptional evidence as well. He calls out the deliberate distortions made by western orientalists.

Thus these insights from Purāṇas and Itihasas are immensely important for a collective nation in the Ādhibhautika or gross physical world.

- It debunks the Aryan Migration/Invasion theory and eurocentrism of historical narratives. It establishes the antiquity of Indian civilization and a common shared history of Indians, much earlier than Greek or other civilizations.

- Purāṇas and Itihasas are not myths, untrue, false or mere fables as propagated. This strengthens the discourse of Hindu scriptures against the negative onslaught of Abrahamic forces and modernity.

- It helps in decolonizing the Indian mind and re-establishing the traditional channels of knowledge. The involuntary urge for looking at white man’s authentication and disdain for Indian subjects can be cured from the psyche.

- Purāṇas and Itihasas open up a Pandora box of research and aide other subjects like archeology, for setting up an Indian narrative in the global power struggle.

Ādhidaivika Insights

The ultimate truth mentioned in the Upaniṣada-s is attainment of the Mokṣa or liberation of the individual along with its associated desires. But an individual self is so full of desires and seeks worldly pleasures like name, fame etc. These come under the other three Puruṣārtha, i.e. Dharma, Artha, and Kāma. Purāṇas and other shastras recognise this several states or levels of an individual’s evolution. Mukti or Mokṣa is not a commandment and renunciation is not everyone’s cup of tea.

Thus Purāṇas talk of worshipping Deva-s for attainment of desired results. Every Deva is a manifestation of certain subtle forces for qualities. Their āradhanā or worship under certain rules is said to bring desired results in Purāṇas. For example Kuber is the deity for wealth. Similarly Indra or Varuna is worshipped for good rain and harvest. Asvini Kumār are deva-s of health and medicine.

The stories and fables guide an individual to attain his desires (artha and kāma) guided by Dharma. The Devatā-s are upholders of Dharma. This path creates a harmonious and upright society. The establishment of Dharmic way helps in proper maintenance of external natural environment as well as psychological conditioning.

Today we can see the consumerist greed is leading to anthropocene hazards as well as rise in mental illness. One can say this is the overpowering of Asura-s or adharmic tendencies. Purāṇas talk of Asura-s overpowering Deva-s. Asura-s represent immoral, unethical subtle forces that manifest within us. So in a way Devas and Asuras are within us. They represent qualities within us which we can elevate.

But the Puranic shastras prescribe the path of Devas as it is based on Dharma. This checks our encroachment on resources and others’ lives. For example a Asura king in Purāṇas will bring havoc to the conquered territory but a Daivika king will bring peace and prosperity to the conquered territory.

The prescribed way to follow the Daivika path is not just external to the practitioner. These stories when taught to children help in their subconscious programming. According to Bruce H. Lipton nearly 95% of our life actions is guided by the subconscious mind. The subconscious mind doesn’t work like the voluntary conscious mind. It is the habits and beliefs that drive us. Subconscious programming happens majorly in childhood which in turn shapes the rest of lives.

So the subtle Daivika qualities manifest in our subconscious thoughts since childhood. Another way to rewrite or change the subconscious programming in adults is via repetition (Lipton,2005). Repetition means complete and continuous action, feeling, chanting and/or belief in a desired mode. As a very basic example, if an unhappy person wants to reprogram his subconscious mind he needs to repeatedly say “I am happy” along with the feeling, continuously, even if he isn’t so. So an adult following the prescriptions of Puranic devatā-s and doing the rituals religiously for a desired outcome is in the process conditioning his subconscious mind. Thus Puranic prescriptions can help in attainment of results via inner conditioning, but most importantly, in Dharmic or true righteousness principle.

These mind sciences are explained otherwise in yogic philosophy too. This Ādhidaivika insights again casts away the inferior status of the Purāṇas generally accorded to them in modern age.

- Purāṇas establishes Dharma in the society by guiding individuals in its path to fulfill their own desires. The recourse to Deva-s and rejection of the Asura-s embed the righteousness principle in stories and fables.

- The working principle can be explained via mind sciences. The desired outcomes are achieved by the individual due to subconscious operation or programming.

Ādhyātmika Insights

According to Yogic sciences the highest goal of an individual “Jiva” is attainment of Sat-Cit-Ānanda. This state is the true existence where there is only permanence without any attributes of change. There is experiencing complete bliss and identifying with the universal consciousness. This is possible by elevating one’s own consciousness. One gets liberated from the limited identity of physical body, mind, intellect and ego.

Modern science is now questioning its earlier hypothesis that consciousness is the result of biochemical reactions in the human brain. While modern science is at a relatively nascent stage, one finds the deep ideas explained in our shastras like Ātma Bodha written by Adi Shankaracharya in yogic vocabulary.

This is considered the highest Knowledge which needs to be attained. This knowledge of Upaniṣadas are very well encoded in the simple stories of Purāṇas. Purāṇas bring to masses the complex truths in an easy to comprehend form.

A spiritual practitioner or a yogi is inspired by the allegories that are present in Puranic stories. The allegories contain the true knowledge of the unity of microcosm and macrocosm. They debunk the reductionist epistemology and deploy a holistic union of the cosmos. For one who seeks the knowledge of the Brahman, the same Puranic fables have different insights for him/her. Thus Purāṇas have different utilities for individuals in different states or levels of evolution.

Story of Dhruva

As an example, the yogic allegories of the story of the child Dhruva from Viṣṇu Purāṇa and Bhāgavata Purāṇa are presented as follows.

The story goes like this. There was a king named Uttānapāda, the son of Manu. He had two wives named Suruchi and Suniti. The son of Suruci was Uttama Kumāra and that of Suniti was Dhruva.

The king slowly started liking Suruci more at the cost of Suniti. Thus Uttam Kumāra was seen close to his father often. One day, Dhruva wanted to sit on the lap of his father in the king’s court. But his step mother, Suruci, wanted the place to be reserved only for her own son –Uttama Kumāra. So she removed Dhruva from the king’s lap and the king remained mum.

Dhruva went crying to his mother Suniti devastated by the act of his step mother. Suniti consoled him by saying – you should try to sit on the lap of the eternal father Viṣṇu or Nārāyana. He went to forests in search of Viṣṇu.

There he met Nārada Muni who taught him the Nārāyana mantra and the meditative techniques. He also met the Sapta Ṛṣi – Kratu, Pulaha, Pulasta, Atri, Angira, Vasistha and Marichi. They asked him to do japa of Hari’s name.

Dhruva started meditating in the forest. Numerous wild animals started howling and frightening him. But he was determined and unperturbed. The penance terrified King Indra who thought Dhruva might take his throne. So he created obstacles like storms, rain etc. But Dhruva was unmoved by them.

Finally Bhagavan Viṣṇu appeared before him and asked him for boon. Dhruva was content and didn’t seek any. He attained Dhruva-pāda and was placed as the pole star in the night sky for millenia to come.

The Yogic allegories of the Dhruva story

This fancy fable reveals itself in yogic parlance to a spiritual seeker in a different way. A yogi sees the story unfolding within his microcosm and not external to him.

Manu who is the creator’s son is the mind within us. All thoughts and emotions whether good or bad, positive or negative, past or future is a product of our mind. It is Swayambhuva meaning self created. Thus we create our own thoughts which influence our actions and bring forth the corresponding results.

Uttānapāda is the son of Manu or the son of mind. Uttānapāda consists of two words – Uttāna and pāda. Uttāna means spread out, stretched out, expanded, elevated or open. Pāda means feet or a position. So Uttānapāda is a state in spiritual practice when one is able to remove negative emotions. He is no more craving for undesirable materials or positions. It can be said he is broad minded.

Such a person can be married to Suruci and Suniti. Now who are Suruci and Suniti? Su is a prefix that means good and desirable. Ruci means attitude or interests. Niti means principles, behavior, showing the way, guiding rules etc. Both are desirable and can be achieved or followed when one discards negative material possession and bad emotions or affection. One can then attach his mind in good deeds and do only good karma. He then gains the status of Uttānapāda.

The son of Suruci and Uttānapāda is Uttama Kumāra. Uttama refers to the superlative quality of good. Kumāra means son. A healthy state of mind can manifest such a son or state. So Uttama Kumāra is the best state of mind. But a spiritual practitioner is not satisfied in this state. In other words, this is not the Ultimate. Why?

Because there is the presence of ego or sense of “I”. One identifies with good things and positions. He is limited by the good or noble characteristics of the mind. There is no cessation of ephemeral activity, though that activity is good karma.

In such a situation the noble mind, Uttānapāda, takes help of Suniti. Suniti meaning proper principles and rules can lead to higher elevation or dimensions. The result of the path is Dhruva Kumāra.

Dhruva means stable, unchangeable, permanent and fixed. When one is attached to good things and thoughts one doesn’t let go of it easily. Therefore, Suruci doesn’t like Dhruva. She likes Uttama Kumāra which suggests enjoying the best of attributes. But Dhruva is the cessation of this liking nature of the mind. One has to move beyond good karma as well for Mokṣa or liberation.

Dhruva then moves to the forests. Forest symbolizes the storehouse of knowledge and that knowledge is also within us. One needs to unravel it. Dhruva meets Nārada who is the Guru guiding a yogi to attain Nārāyana. He teaches him Prāṇa Vidyā or the technique to know the life force- Prāṇa. This is the highest Knowledge. The seven Ṛṣi are symbolic of the seven Chakras in the spinal column. A yogi needs to activate them from their potential state to raise his level of consciousness. This is explained by the encounter of Dhruva with the seven Rishis.

Dhruva while in the meditative state is disturbed by wild beasts. Wild beasts are attributes of mind, the impermanent desires, insatiable and unregulated. These are obstacles that every spiritual person encounters. Indra is the lord of senses. In the path of spirituality one has to master the sensory lords as well. This is explained by Dhruva mastering his fears created by storms and rains of Indra.

A determined practice and continuous quest for the Ultimate Reality will result in one realizing Viṣṇu or Nārāyana or Vāsudeva. He is the universal consciousness that shines within us yet there are no desires or activity in him. He is unborn and uncreated. He is the Life force or the Prāṇa that flows within us.

Dhruva Kumāra attains this state of Samādhi known as Dhruva pāda. He merges in the Nārāyana. He has no craving for a boon with cessation of karma. This is the liberation of a Jiva. He is able to guide the other seekers and yogis like a pole star shows the north direction in a dark night. The seven Ṛṣi or Sapta Ṛṣi who are the seven subtle centres or chakras within us rotate around Dhruva. Their activation within the microcosm will lead to attainment of the state of Dhruva pada.

This story shows the spiritual journey of every individual from Uttānapāda to Uttam Kumāraa to Dhruva Kumāra and finally Dhruva Pada. The journey is from discarding negative emotions to positive thoughts. Further from the highest state of positive thoughts to the Ultimate state of thoughtlessness. This is cessation of any identity or desires. The Ultimate state is Sat, Cit, Ānanda as described in the Upaniṣadas.

The story from Devi Mahatmya

Let us now look another such story -the story of the first chapter of Devi Mahatmya or Chandi, which is a part of Markandeya Purāṇa, is reproduced with its decoded insights.

The Devi in the first chapter of ŚrīDurgāSaptaśatī is Mahākalī. There is the hidden meaning of Mahākalī Upāsanā. The story of the first chapter of ŚrīDurgāSaptaśatī goes like this. There was an emperor named Suratha. He ruled over the entire earth by following his Dharma and treated the commoners like his own son. At this time a king became his enemy and attacked him. He was defeated on the battlefield and had to return to his own city.

But he was again attacked and was looking weak on the battlefield. Thus, his powerful ministers turned wicked and treacherous and took over the emperor’s wealth. After losing his authority he escaped into a dense forest.

He was roaming in the forest when he saw the Āśrama of sage Medhā where many wild animals were resting peacefully. He stayed there for some time. But the thoughts of his once-prosperous kingdom built by his ancestors kept haunting him. He was worried about the future of his people, the empire’s wealth, and so on.

During those days emperor Suratha met a dejected Vaiśya named Samādhi. The Vaiśya was from a wealthy family. But his wicked wife and son pushed him out from the house out of greed for his wealth. His relatives also took away his money. Thus drowned in sorrow he took the road towards the forest. Yet he was craving for his son, wife, and relatives.

The emperor after knowing all this asked him why he is yet filled with affection towards those who cheated on him. Samādhi replied that despite knowing the enormous harm inflicted upon him, he is filled with pity for his son and wife. He was unable to understand this predicament of life. The Vaiśya wanted to get away from such a miserable situation.

So, the emperor and the trader went to Medhā Muni. They sat under the feet of the sage. The emperor then said his mind is not under his control which is making him miserable. He lost his whole empire. He was attached to each and everything of his empire.

In spite of knowing that it is no more, he is filled with despair like a stupid person. And this fellow who was insulted by his wife and son and thrown out of his house is worried for their well being.

Why were they remorseful despite directly knowing the situations that were at fault? Despite being learned, why were they craving thus like foolish persons?

Hearing all this, the sage replied this is not something peculiar with them or for that matter any other human being. The animals too have direct knowledge of their circumstances. A bird in spite of being in hunger first feeds her young ones with grains.

Similarly, a man craves for his son. Everyone is knowledgeable yet they are under the influence of Bhagavatī Mahāmāyā.

This whole world is filled with Māyā by her. She is the Yoganidrārupā of Bhagavān Viṣṇu. The creation, preservation, and destruction of the entire universe are under her control. Only when she is pleased, one gets Mukti from her Māyā.

On further query, the sage described the Mahāmāyā. She is indestructible, unchangeable, and eternal. She neither takes birth nor dies.

The whole world is her creation yet she takes different forms at different times. To explain all this Medhā Muni started narrating a story of the creation to the emperor and the trader.

The Madhu- Kaiṭabha story

Once Bhagavān Viṣṇu was sleeping in Yoganidrā, after the end of time when from the dirt of his ears two Asura named Madhu and Kaiṭabha took birth. These two went towards Brahmāji, who was just born and sitting on the lotus stem arising from the navel of Viṣṇu, to kill him.

Seeing the two Asura coming towards him and Viṣṇu sleeping, Brahmāji started praying to the Yoganidrā with full concentration. He prayed her for waking up Bhagavān Viṣṇu and endow him with intellect to kill those Asura.

Being pleased with the prayers Devi Yoganidrā came out from Viṣṇu. Being freed from Yoganidrā, Viṣṇu woke up from his sleep. He saw the two Asura with red eyes going to engulf Brahmā. Thus he started fighting with them.

The fight went on for thousands of years. Both were out of their mind due to their power and were even engulfed by Māyā. So they asked Viṣṇu to seek a boon from them. Viṣṇu asked them if they are pleased, then get killed by his hands.

They came to know they were betrayed. But they saw the world was then filled with water. Hence, cunningly both asked to be killed in a dry place. Viṣṇu then put their heads on his thigh and killed with his Cakra. This is how sage Medhā narrated a story of how Devi Mahāmāyā took form on being worshipped by Brahmā.

Is this only a story?

It is easy to dismiss this story as a myth or just another fable for a person outside of the tradition. But in this way, we lose the epistemology of this simple yet deep story. Worse is several distortions and prejudices creep in against this beautiful tradition. Let us now look at what the story holds.

The symbolism of Chariot

The emperor was named Suratha. Ratha means a chariot. Now a chariot symbolizes the physical body. The charioteer (Sārathī) is the intellect that drives the chariot i.e. body. The mind is the reins of the chariot which is in the hands of the charioteer (intellect).

The reins (mind) control the horses. The horses refer to the sensory organs. The paths on which the horses (sensory organ) run are the circumstances/sensory objects of the material world.

The owner (Rathī) of this whole chariot set up is the Ātmā. This Jīvātmā (owner) is Bhoktā, when it is attached to the chariot (body), reins (mind), and the horses (sensory organs). So there is the crisis of identity and chaos prevails.

It is so because the owner (Jīvātmā) enjoys the pleasure and suffers the pain of the chariot (body) inflicted by the unrestrained mind (reins) controlling the horses (sensory organs). The true nature of the owner is to be a witness (Draṣṭā) of the set up not to be a Bhoktā (being attached) of the body-mind.

The emperor was Suratha meaning he was filled with noble qualities (Satva Guṇa). So he ruled with Dharma. Yet he was attached (Bhoktā). He was attached to his wealth, his people, and his kingdom. Thus his identity was determined by the impermanent material world.

Naturally, when he kept losing, he became miserable and weak. The wicked and treacherous ministers taking over of the wealth means the rise of Tāmasik Guṇa (destructive qualities). It is a state of darkness, negativity, and inactivity.

Who was Medhā Muni?

The emperor then wanders towards the forest. Forest represents life, a storehouse of knowledge, and inclusivity. Thus the journey into the forest is the seeking of the king driven by the intellect (charioteer or Sārathī).

In the Āśrama of Medhā Muni, the wild animals were resting peacefully. Isn’t it strange? The sage name was Medhā, meaning higher intelligence. He was enlightened with the ultimate truth of the body-mind complex. He is only witnessing all pleasures and pain without being affected.

Thus the resting wild beasts symbolize peace and tranquility. There is no chaos or crisis of identity.

The Nature of Mind

The thoughts of the emperor speak of the nature of the mind. The unrestrained mind always attaches itself either with the past or future. The emperor missed the prosperous kingdom of his ancestors and worried about the future of his people. The role of higher intellect is to guide the mind to the present moment and help it get away from the self-inflicted injury.

The Vaiśya name was Samādhi. The word means to hold oneself in a constant, unchanged, or homogenous state of consciousness. There are no transitory moments of pleasure or pain.

The role of a Vaiśya is to look for profit but here Samādhi is looking for true profit. He is seeking answers for the changing miserable state of his mind. The state of mind is to crave pleasure and being averse to pain.

In this state of craving and aversion of future and past subjects, both the emperor and the trader go to the higher intellect (Medhā). He can help solve the crisis of body-mind. Everybody is rational and learned, yet they fail to get out of this habit pattern of mind.

Humans are no different than animals and birds when they are attached to the chariot of body-mind. This is the true knowledge that he imparts through another story.

What is Māyā?

Māyā is today wrongly conceived as something evil or illusion. Māyā is not good or evil. It is simply a statement of facts. It is the nature of the universe.

This nature the emperor and the trader are unable to comprehend. There is nothing to idealize or detest in this. Māyā is that which exists and at the same time does not exist.

This is apparent existence and the nature of real existence. It is the creation of Mahāmāyā. She is defined as indestructible, unchangeable, and timeless.

It is only the sensory organs and the minds that see birth and death and observe the changes in time. Mahāmāyā is beyond senses yet she is the all-pervading principle. She is inseparable from existence and eternal.

The owner of the chariot – Rathī (Jīvātmā) has to be detached from the chariot (body-mind) and be a witness to comprehend her. She is the Devi of Tāmasik Guṇa. So she is fierce, dark, and ugly.

Yet she is beautiful, soothing, and caring. So when she is inside Viṣṇu, he is in deep slumber, in a state of idleness and blissful inactivity. He is in Yoganidrā. Brahmā sits on the navel of Viṣṇu.

The navel center is the womb of creation. The womb of Viṣṇu is the Hiraṇyagarbha. It is the cosmic womb, the womb of creation of all the universe, the all-pervading consciousness. So Brahmā, the creator, sits there.

Are Madhu and Kaiṭabha dead?

The two Asura named Madhu and Kaiṭabha is born from the dirt of the ear of Viṣṇu. What does this mean? Ear symbolizes sound. Everything we see is waves of vibration. The simplest of sub-atomic particles are also vibrating. Our thoughts are even subtle vibrations.

Dirt symbolizes knowledge devoid of distinguishing intellect. So the two Asura are our thoughts unable to distinguish what is desirable and undesirable.

Madhu is craving for pleasure and Kaiṭabha is averse to pain. So they are the nature of our mind that overpowers our intellect. They have red eyes referring to anger, lust, greed, and other emotions that take over us.

Brahmā prays to Yoganidrā and asks her to come out of Viṣṇu. As long as Tāmasik Guṇa is within us we can’t fight against our mind. So Brahmāji worshipped her with Ekāgra Citta – complete concentration to win over the pulsating nature of mind.

With Tāmasik Guṇa out of Viṣṇu, he was able to fight the two Asura (craving and aversion). But the fight went on for thousands of years. This conveys it is not easy to get mastery over the mind and be detached in a short span. One needs perseverance and dedicated effort.

The Asura, Madhu (craving), and Kaiṭabha (aversion) are mad in power. Similarly, our mind loses sanity when engulfed in these two traits. But it is not fatalistic. They can be tricked and tamed with practice just as the two Asura were tricked by Viṣṇu.

But why they couldn’t be killed in water and had to be killed on thighs? This is again symbolism at play. Water pervading everywhere is Prāṇa – the life force. There is no death here rather boundless life. On the other hand, the thigh symbolizes sexuality.

The mind is always associated with sensory objects. When one is deeply attached to sensory objects it is a state of death. Hence, they were killed upon thighs.

Thus from the Adhyatmika Insights it can be concluded that

- Puranic legends are based on the Ultimate Knowledge of Self and Brahman of Upaniṣadas. They bring to common folks the deep philosophical metaphysics in a lucid manner.

- The Puranic stories act as guides and inspirations to spiritual practitioners. This may be simple fables, yet held in reverence, for others.

- Thus there lies multiple layers of meanings in Puranic legends which are revealed depending upon one’s state.

Click here to watch the presentation of this paper.

References

-

- Bala S. & Mishra K. (2012). Historicity of Vedic and Ramayana Eras Scientific Evidences from the Depths of Oceans to the Heights of Skies .Institute of Scientific Research on Vedas I-SERVE Delhi Chapter.

- Giri S.N. (2007). Dhruva – The Pole Star. Hiranyagarbha, August 2007.

- Giri S.N. (2013). Kriya-yoga. The Science of Life Force. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Kathokapanishad (2000). Kailash Vidya Prakashan.

- Lipton B.H. (2005). The Biology of Belief: Unleashing the Power of Consciousness, Matter and Miracles (2008). Hay House, INC.

- Malhotra R. & Neelakandan A. (2012). Breaking India. Western Interventions in Dravidian and Dalit Faultlines. Wetland Ltd.

- Panda A.K. (2020). Decoding the Profound Story of the First Chapter of SriDurgaSaptasati. INDICTODAY https://www.indictoday.com/long-reads/decoding-profound-story-first-chapter-sridurgasaptasati/

- Shashtri Sri R. SriDurgaSaptasati, Hindi Translation. Gita Press, Gorakhpur.

- Venkatchelam, P.K. (1951). Indian Eras(2019). Kota Venkatchelam Historical Research Institute (KVCHRI) Arya Vijnanam.

- Venkatchelam, P.K. (1952). Age of Mahabharata War(2019). Kota Venkatchelam Historical Research Institute (KVCHRI) Arya Vijnanam.

This paper was presented as a part of a Conference on Puranas and Indic Knowledge Systems, organized by Indic Academy on 26th and 27th March 2021.

(Image credit: waccglobal.org)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.