(This is the seventh article of the series titled ‘Unknown Tales from the Puranas’. There are myriad stories from puranas and upapuranas that are hardly known to most of us. The series will cover such lesser known tales, as well as unknown versions of the popular tales from pauranika sources. Read the earlier story here. The present story is about the first interactions between the sacred Trimurti- Brahma, Vishnu, and Maheshvara.)

Both vāda, i.e., debate, and saṁvāda, i.e., dialogue are critical in the development of any knowledge system. Technical methods of discussion, dialogue, and debate are used to resolve a multitude of internal conflicts, which primarily arise out of a feeling of superiority and competition in rival traditions within the system.

Puranic tradition is no exception to this rule. The sectarian nature of the purāṇas results in a lot of conflict between the major puranic panthas like Viṣṇu, Śiva, Devī, and Brahmā. It can be observed in numerous situations in purāṇas and upapurāṇas that there has been a constant one-upmanship in these divinities.

It is also seen at times, that two or more deities share attributes, activities, titles, and more. They also influence each other in terms of appearance, choices, festivities, and modes of worship. This dialogue between the deities is the fulcrum of puranic theology, which in turn has shaped Hinduism as we see and practice today. This is why understanding the underlining dialogue and debate in puranic lore becomes essential.

The following article seeks to understand the dialogue and debate in the puranic tradition with the help of a unique incidence cited in Kūrmamahāpurāṇa[1] as a case study.

Padmapurāṇa labels Kūrmapurāṇa as a Śaiva or Tāmasa purāṇa, while Bhaviṣyapurāṇa tags it as a Brāhma or Rājasa purāṇa. However, in opinion of R. C. Hazra, the Kūrmamahāpurāṇa originally belonged to the Pāñcarātras and afterwards was appropriated by the Pāśupatas.[2] Dr. G. V. Tagare notes that it presents the teachings of Tantrism and sun-worship as well.[3] This assorted ambiguity of Kūrmapurāṇa makes it interesting to observe and analyze the puranic theology therein.

The incidence of Hari–hara–brahmā–saṁvāda that forms the basis of this article, throws light on the complexity of exchanges between Vaiṣṇava, Śaiva, Brāhma, and Śākta sects; simultaneously explaining how this reciprocation shapes the puranic theological environment.

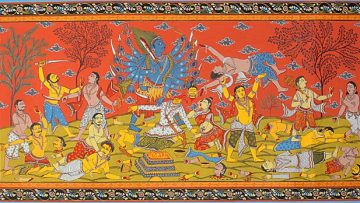

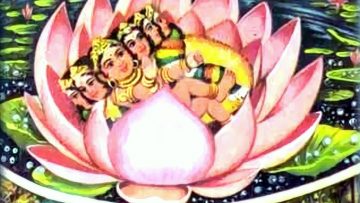

Let us begin by understanding the outlines of these episodes in brief. Chapter 9 of Pūrvārdha titled Padmodbhava-prādurbhāva explains the dialogue between Viṣṇu and Brahmā at the beginning of a new kalpa. As Viṣṇu was resting on Śeṣa in the abyss after the dissolution of previous kalpa, a lotus bloomed out of his belly button. After a long while, Brahmā approached him. When each one sought an introduction of the other, both introduced themselves as the greatest divinity.

Viṣṇu then entered the body of Brahmā for a closer inspection, where he saw the three worlds. He came out from Brahmā’s mouth. When Brahmā entered the body of Viṣṇu, he also witnessed the same three worlds. However, Viṣṇu closed all the outlets of his body. Finding no other way, Brahmā came out from his belly, through the lotus. Brahmā then enquired about the mischief, and boasted that no one can overpower the creator of the three worlds.

Viṣṇu duly apologized and clarified, that it was not to overpower Brahmā, but was merely a līlā. He requested Brahmā to be known as his son, Padmayoni. Brahmā granted him the said boon, and stated that Viṣṇu and Brahmā himself were in fact one image split into two. He also indicated that there was no other god apart from two of them. He says, नावाभ्यां विद्यते ह्यन्यो लोकानां परमेश्वरः। एका मूर्तिर्द्विधा भिन्ना नारायणपितामहौ ॥ (9.40).

Viṣṇu then asked him to reconsider his bold statement, as there also was Maheśvara who in fact was beginning-less and end-less Brahman. Brahmā initially denied the equivalency of Maheśvara. At that very moment, there appeared the three-eyed, trident-bearing Maheśvara. Brahmā was however under the influence of pārameśvarī māyā, and could not recognize him. Viṣṇu offered him divine eyes to be able to see and comprehend the real nature of Maheśvara. After understanding the reality of Maheśvara, Brahmā prostrated before him and eulogized him.

Maheśvara addressed Brahmā as being equal to Maheśvara himself, and granted him a boon. Brahmā requested Maheśvara that he desired either him as a son or a son like him. Maheśvara granted him the said boon, and told Viṣṇu that he, i.e., Viṣṇu and Maheśvara were in fact equals. भवान् सर्वस्य कार्यस्य कर्ताहमधिदेवतम् । त्वन्मयं मन्मयं चैव सर्वमेतन्न संशयः॥ (9.82 cd-83 ab). He also proceeded to state एकीभावेन पश्यन्ति योगिनो ब्रह्मवादिनः। त्वामनाश्रित्य विश्वात्मन्न योगी मामुपैष्यति ॥ (9.86).

It is worthwhile to note a few observations here. It is striking that the origin or birth of the trinity is not mentioned, probably to highlight their beginning-less-ness and subsequent endlessness. The episode is surely vaiṣṇava in nature as Viṣṇu is portrayed as the most knowledgeable and superior. He knows the identity and worth of both, Brahmā and Śiva. He is also aware of the power of illusion Śiva possesses.

Another interesting aspect is the boons asked for and received by Viṣṇu and Brahmā. Viṣṇu asks for Brahmā to be his son and Brahmā asks for Śiva to be his son. Here again, Viṣṇu is at the pinnacle. There obviously are clear attempts of synthesis of the three sects. The verses नावाभ्यां विद्यते ह्यन्यो लोकानां परमेश्वरः। एका मूर्तिर्द्विधा भिन्ना नारायणपितामहौ ॥ (9.40) and एकीभावेन पश्यन्ति योगिनो ब्रह्मवादिनः। त्वामनाश्रित्य विश्वात्मन्न योगी मामुपैष्यति ॥ (9.86) cited earlier, are sufficient to prove this point.

If we observe these stories from a socio-religious point of view, we realize that alongside the rivalry and one-upmanship, the effort of an assimilative and integrative sectarian synthesis is made by the puranic bards. The very background of composition of these magnanimous texts was to float a religion identifiable for masses (probably at the backdrop of popularity of Buddhism and Jainism).

The process therefore, does not stop at mere amalgamation, but takes a step further by establishing identifiability, likability, and approachability for all the members of that synthesis. This synthetism in the deities is logical, and in accordance with the fundamental spirit of the Upaniṣads, that this all is Brahman.

In words of Kūrmapurāṇa, पुरुषः परतोऽव्यक्तो ब्रह्मत्वं समुपागमत् । तस्माद्ब्रह्मा महादेवो विष्णुर्विश्वेश्वरः परः॥ (I.2.97) This very approach led paurāṇikas to find a link among all things, creatures, creeds, thoughts, sects, and systems through their witty myths[4], and thereby establish a sectarian harmony.

End Notes:

[1] The Kūrmamahāpurāṇam, Ed. Dr. C. R. Swaminatha, Nag Publishers, Third Edition, Delhi, 2002 (1983)

[2] Studies in the Purāṇic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs, R. C. Hazra, The University of Dacca, First Edition, Dacca, 1940, p.58

[3] The Kūrma-purāṇa, Part I, Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology Series, Vol. 20, Trans. G. V. Tagare, Ed. Prof. J. L. Shastri, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Delhi, Reprint, 1998 (First Edition, 1981), Introduction, p. xxxiii

[4] Prof. Pushpendra Shastri,, Introduction to Purāṇas ( The Light-House of Indian Culture), Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, 1st edition, New Delhi, 1995, Introduction, p. xvi

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.