The festival of Navaratri is here and once again, it is the time to celebrate the Divine Feminine. To be sure, Navaratri comes four times in a year but the Sharad or Autumn Navaratri is undoubtedly the most popular of them all, because of its association with the festival of Dussehra or Durga Puja celebrated with pomp and glory in various parts of the country.

The first set of nine nights dedicated to the goddess comes in spring and is known as Chaitra or Vasant Navaratri. It ushers in the Hindu New Year known as Gudi Padwa or Yugadi and ends with the festival of Rama Navmi. The second set of Navaratri falls during the monsoon month of Ashadh while the final one is the Magh Navaratri that arrives during winter. Through these festivals, the worship of the Divine Mother is associated with the arrival of new seasons, since Nature or Prakriti is one of the manifestations of the Mother Goddess in Hindu belief.

It is perhaps unfortunate that the celebration of divinity in its feminine form, that was widespread in all ancient cultures of the world, had to take a backseat with the arrival of western monotheistic concepts of One Supreme male god who exists without a second. In India, the worship of the Mother Goddess has been prevalent since at least the Indus Valley days and goddess figurines have been discovered in places as far as Sumeria, Austria and Turkey.

Ancient Japanese, Egyptian as well as Greek civilizations also had a healthy regard for the role of goddesses in their pantheons just like they did and still do in India. Shiva and Shakti are the Primal Male and Female in the Hindu pantheon and it is only through their cosmic union that creation can manifest. The same notion is reflected in the Chinese concept of Yin and Yang that observes everything as a mix of opposing yet inseparable principles that complement each other perfectly.

The Eastern belief systems have always approached God in a more fluid way, with each practitioner free to imagine God in the image that is closest to his/her heart. That is why you find numerous sects thriving right next to each other in India since time immemorial. Even today, many people in India continue to venerate the source of this entire creation as the Primeval Feminine Force or Aadi Shakti. Each of the nine days of Navaratri is associated with one of the innumerable forms of the Supreme Goddess that also manage to find resonance with the different stages of a woman’s life in the society.

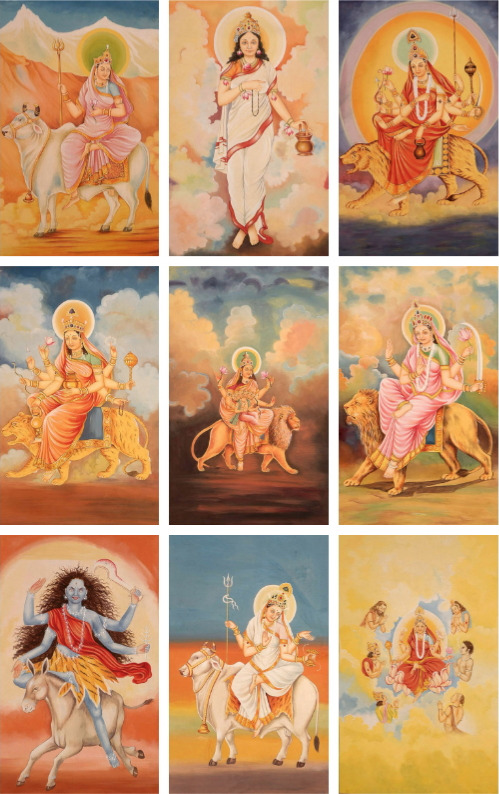

The first three forms depict the transformation of a young girl whose identity depends on her parents, to an adolescent who perseveres to fulfill her desires, and then to a grown up woman who has stepped into her new role of matrimony with finesse. The first day is dedicated to Shailaputri, or the daughter of the mountains, referring to goddess Parvati’s birth in the family of the king of Himalayas. The second form of Brahmacharini highlights the penance she takes to be re-united with her soul-mate Shiva and the third day is dedicated to Chandraghanta, the goddess who is married and rides a tiger, carrying the weapons she needs to protect her devotees.

The next three forms of the goddess reflect three more facets of a woman’s social persona. Kushmanda, the goddess of the fourth day, wears an enigmatic smile and shines with the splendor of the Sun. She is the woman who has mastered the ways of the world and is not only thriving but also sharing her magnificence with the entire creation. The fifth form of Skandamata shows the goddess as the nurturer, holding her infant son Skanda or Kartikeya in her lap. Devoid of any weapons, yet riding a fierce lion, she is quite literally, the mother of god!

Many modernists scoff at the idea of depicting women as mothers because they think it relegates them to an inferior role. Nothing could be more erroneous since in the ancient Indian perspective, the mother holds much more importance than the father. The scriptures are full of examples of strong, independent mothers who took their children to new pinnacles of success with little to no contribution from their fathers. Would mention a few well-known examples just to highlight my point – Aditi, the mother of Devas whose sons rule the heavens; Kunti, the mother of Pandavas whose sons come out of the forest and become sovereigns of the whole naton; and Jaratkaru, the mother of Rishi Astik who helps stop a terrible snake-sacrifice that would have wiped and entire species from our planet.

The sixth form of Katyayani is again associated with something momentous. She is the one who appeared as Durga to destroy the demon Mahishasura and her victory is the most depicted scene in all Durga Pujo pandals. She steps in when even the gods are rendered powerless by the boons given to the buffalo-demon and it highlight the inherent potential inside a woman – she is not just equal to men but is in fact superior to their entire lot!

The seventh depiction is that of Kalaratri and perhaps represents the pinnacle of the ancient Indian feminist movement. It is a natural progression from the goddess that has proven herself better than her male counterparts but it also differs from her in a significant aspect. While all the other goddesses form a part of the society in some way or other, Ma Kali is beyond the confines of social boundaries. She is dark, threatening, and has blood dripping from her fangs. She holds a man’s decapitated head in her hand and is adorned with the skulls of demons she has destroyed. She is standing on her spouse Shiva who lies calmly below her feet, showing the world that in this relation, it is the woman who is on top.

Parvati, the beautiful and fair wife who expertly balances her personal and professional life is transformed into the dark destroyer Kali who doesn’t give a hoot about how she looks or what social obligations she has to fulfill. Once she has subdued not just the demons but also the gods, and revealed to the entire creation who she can be if she just puts her mind to it, she returns to the benign aspect of Mahagauri, the goddess of the eighth day. Bringing respite to a bewildered world, she rides the bull that is the vehicle of her husband and holds his trident, once again showing the world that Shakti and Shiva are two different halves of the same whole.

The final form of the ninth day is that of Siddhidatri, the giver of spiritual powers that all ascetics and Yogis aim for. She holds in her four hands the conch, lotus, club and discus and is worshiped by humans, the Gandharvas, the gods and even the demons. She is the final form that has come about through the process of her evolution from a daughter to a lover to a wife to a mother to a wildling. She is the epitome of Divine Feminine, who holds the nurturing aspects of the lotus and conch shell in her hands along with the supreme weapons of Lord Vishnu that have the power to destroy the creation.

The Navadurgas therefore depict stages of a woman’s divinity, and none of them is inferior to the other, just as a woman taking care of her family is no less than one who frequents the corporate boardrooms. This Navaratri, let us understand the true meaning of the different depictions of the goddess and recognize the same divinity in the women around us.

Jai Mata Di!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.