In the first part of this two part series focusing on the emotion of Envy, we learnt that despite the popular belief and the main proponent of the emotion in the epic tale, Duryodhan wasn’t the only person driven by envy.

Let us now continue with more examples of envy as we meander through other stories and in the process receive our lessons from Mahabharata. While we are at it, let’s also see if there is some common thread connecting them.

Having married Droupadi and having settled in Indraprastha, the Pandvas were once visited by the sage Narada. They all greeted the sage, and after Droupadi left, Narada had a pointed question for the Pandavas. Given Droupadi’s beauty, how were they going to head off the green-headed monster that was envy? To illustrate his point, he told them the story of the two invincible asuras Sunda and Upasunda, who once lived in Kurukshetra. Yes, all roads did seem to lead to Kurukshetra.

Sunda and Upasunda were the sons of Nikumba, who belonged to Hiranyakashipu’s lineage. The two brothers were inseparable, and like-minded in their desire to conquer the three worlds. They prayed and prayed and finally appeased Brahma, who wished to grant them a boon. They asked for knowledge of all weapons, strength, etcetera, etcetera, and oh yes – immortality. Brahma granted them all they wanted, except for immortality. He did tell them that they could choose a means of their death. I did say they were from Hiranyakashipu’s lineage, right? So they were smart. Knowing how deeply their fraternal love was, they asked they be invulnerable against everyone and everything, except themselves. Yes, too clever by half, one might say. It was Vishnu who killed Hiranyakashipu in his Narasimha avatar – neither man nor beast, with weapons that were neither held in the hand nor released, neither on earth nor in the skies, when it was neither day nor night. In the case of Sunda and Upasunda, it was not Vishnu but an apsara named Tilottama. She was created by Vishwakarma, at the behest of Brahma. She was so named because every part of her was perfect. Get the picture? Yes, I am sure you have. When Sunda and Upasunda spotted Tilottama, the scene unfolded like from a movie. One grasped her right hand, the other her left. One proclaimed her to be his wife, and the other’s sister-in-law, and vice-versa. Unable to restrain themselves, they came to blows. Since both could be killed only by the other, Tilottama became the vehicle for the destruction of both. Envy and possessiveness was their undoing.

Sund and Upasunda fighting over Tilottama [image credit: Gita Press, Gorakhpur]

A picture is worth a thousand words, and Narada had painted a vivid portrait for the Pandavas. They got the message and they agreed upon this rule – “If any one of them set eyes on Droupadi when she was lying with any one of the others, he would retire to the forest and live the life of a brahmachari for twelve years.” As fate would have it, Arjun ended up going to the chamber when Droupadi was with Yudhishthira, to help a brahmin whose cattle had been stolen by thieves. As a result, he had to leave Indraprastha. That he did, but live a life of a brahmachari he certainly did not. His travels led him to Dwarka, where he ended up marrying Krishna and Balarama’s younger sister, Subhadra. Her son Abhimanyu played a central role in the Mahabharata on the thirteenth day of battle, while his posthumous son we covered in the previous tale.

Envy was the undoing of Sunda and Upasunda, but thanks to Narada’s advice, it saved the Pandavas.

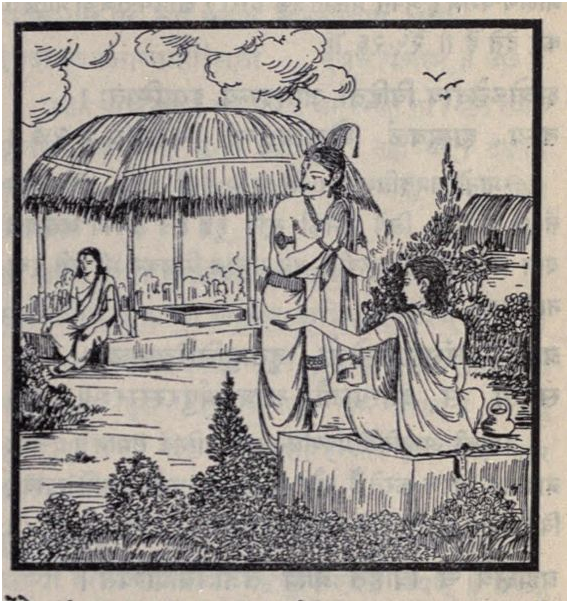

Since we are talking of Droupadi, let’s go back in time to the birth of the Panchala princess. Having been defeated by Drona, Drupada thirsted for revenge against his childhood friend and now guru to the Kuru princes. His travels led him to two brahmarishis, Yaja and Upayaja. The younger was more knowledgeable than the elder, and therefore Drupada showered all his attentions on the younger brother. Upayaja refused, but Drupada persisted. After much time, Upayaja told Drupada to try his luck with his elder brother. Why? Because Upayaja believed his brother “desired material fruit.” Yaja, the elder, did not refuse Drupada’s entreaties. While Drupada had made an offer of ten crore cows to Upayaja, he offered only eighty-thousand cows to the elder brother. Yaja desired material fruit, or perhaps he was envious of his younger brother’s fame and prowess. In any case, he agreed, and performed the yagya. But even here there was a twist. At the appointed hour, Drupad’s wife was not ready. But Yaja did not wait. He poured the sacrificial offerings into the fire, and from that fire of envy, by envy, was born Dhrishtadyumna, and then Droupadi.

Drupada with Yaja and Upayaja [image credit: Gita Press, Gorakhpur]

I began with Droupadi, so I will finish with Droupadi. After Bhima had killed Bakasura, the Pandavas continued to live in the brahmana’s house for some more time. A brahmana visited their house and spoke to them about Droupadi’s upcoming svayamvar and also the story of her birth. Such was the brahmana’s account of “form and supreme beauty” that “that she had no equal on earth.” Kunti looked at her sons and saw that Kamadeva’s arrows had speared all of them, and “On seeing that her sons were confused and not in control of their senses,” she made the decision to go to Panchala for Droupadi’s svayamvar. Kunti saw effect a mere description of Droupadi’s beauty had on her sons. Would she not have been aware of the effect were one of them to win her hand in the svayamvar? Was her instruction to her sons to share the “alms” they had brought for her so cast in stone that she could not take it back? Did that become a convenient vehicle to ensure her sons’ unity? Yes, there was Nilayani’s boon by Shiva that was also in play, but that is a story for another time.

Disclaimer: views expressed are personal.

Source: Unabridged English translation of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute’s Critical Edition of the Mahabharata, Vols 1-10, translated by Bibek Debroy (published by Penguin, 2010 – 2014).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.