Apsaras, the celestial beauties of Devalok as described in Indic and Puranic scriptures gracefully immigrated to China through the ancient Silk Route. These flying Chinese Apsaras, the mythical cosmic creations of Indian origin trekked along with the envoys of Bodhisattva to the Chinese landscape.

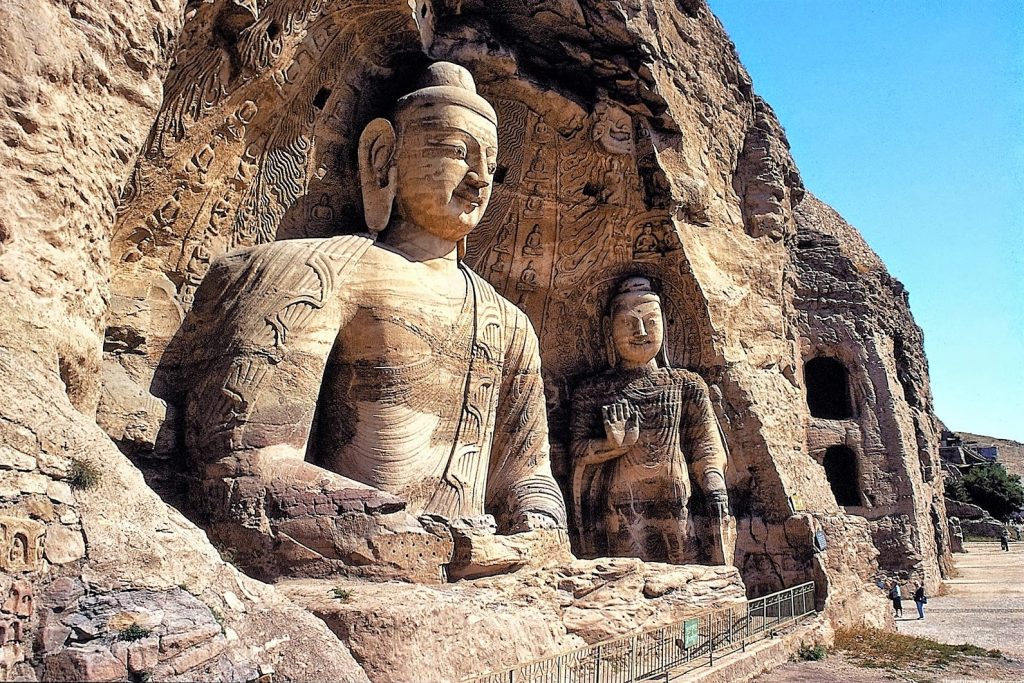

Apsaras or Feitian as they are referred to in Chinese are magnificent flying figures seen dancing and playing celestial music in the frieze paintings and sculptures of Buddhist cave sites in China. These sacred floating Apsaras can be seen in the Magao Caves, Yulin Caves, and the Yungana and Longmen Grottoes.

The Chinese Feitian is much similar to the Indian Apsara and is regarded as a Goddess of cloud and water, dwelling in tarns and swamps. She is also said to be the lover of a God named Jiletian. In Buddhist scripture, the Feitian is called the Divine deity of heavenly music, carrying a whiff of aroma. She is also referred to as the fragrant Goddess with a sweet voice. These water nymphs could be seen flying pleasantly and freely below the Bodhi tree.

Thus, Apsara originally made its way from India to China along with Buddhism and was later classified as sacred Buddhist figures.

The propagation of Buddhism from India to neighboring China was initiated between or before the 1st century. The Han Dynasty took Buddhism to China through the Silk Route via the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory bordering the Tarim basin.

An account in the Mouzi Lihuolun, the classic Chinese Buddhist text, gives credit to Emperor Ming Ti of the Han dynasty for introducing Buddhism in China. Mouzi writes that once emperor Ming dreamt of a God whose body carried the brilliance of the Sun and then he saw God flying around Ming’s palace.

The next day the emperor asked his officials: “What God is this?” Fu Yi, a scholar in his court responded and informed that he had heard that in India there is somebody who has attained the Dao and who is called Buddha. He further added that this God could fly in the air; his body had the brilliance of the Sun and finally concluded that He must be the same God the emperor had dreamt of. Thereafter Emperor Ming Ti sent emissaries to India and Buddhism made its entry into China.

Buddhism promoted the concept of Bodhisattva, the branch of Buddhism written mainly in Sanskrit, popularly known as Mahayana Buddhism. The first documented translation of Buddhist scriptures from various Indian languages into Chinese occurred in 148 CE by Parthian, the prince-turned-monk.

The introduction of Mahayana Buddhist teachings further facilitated in adding Indian influence on Chinese art, literature, and culture. Buddhist mythology consisted of tales of the Buddha’s life and information derived from Vedic texts as well as popular Indian folklore.

Along with Buddhist discourse, India had successfully transported the Sanskrit language, Indic myths, legends, epics, Gods, Demi-Gods, Apsaras, Gandharvas, and Rakshasas to China.

With the influence of Buddhism, cave temples were created in Dunhuang and other places. The Mogao Caves in the desert of Northwest China narrate the chronicle of art and Buddhism that started almost more than 1,500 years ago. A UNESCO World Heritage site, a collection of nearly 500 caves are collectively known as the Mogao caves.

These caves are carved in cliffs for about 15 miles in the town of Dunhuang in Gansu province. These grottoes reveal a fortune of sculptures, manuscripts, painted scrolls, and wall paintings dated from the 4th to the 14th century. The first Mogao cave was built in 366 CE, and later dynasties that followed continued to construct caves in Dunhuang for almost a thousand years until the decline of the Silk Route.

Indian Buddhism penetrated through all aspects of Chinese literature, art, poetry, and performing art. Indian dance began to spread to China. Within 2,000 years, Indian dance influenced the Chinese palace and folk dance directly or indirectly.

The modification, adaptation, and integration of Indian Buddhism dance lead to the creation of different styles of Chinese Buddhist dance forms. The Folk Buddhism dance, Tibetan Buddhism dance, Southern Buddhism dance and most importantly the Dunhuang dance draws its inspiration from the frescos of Mogao Caves in Dunhuang. During festivals or temple fairs, there would be rich and colorful Buddhism dance performances.

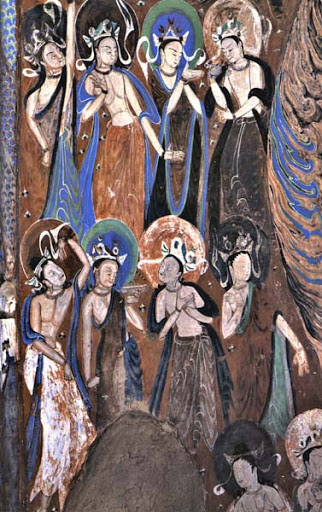

The Dunhuang wall frescos narrate the growth of Apsara images that developed in Dunhuang caves from the Northern Liang Dynasty to the Tang dynasty. The Dunhuang cave nymphs had long-lasting fame and authority. The Apsara motif was typical in Dunhuang art and almost five thousand pieces of Apsaras were shown on Dunhuang wall paintings.

There are two hundred and forty grottoes depicting dance and music. The frescoes in these caves show four thousand instruments in forty-four groups and three thousand performers, and five hundred groups of bands of all kinds.

The Dunhuang dance can be seen gathering its basics and inspiration from the Dunhuang frescoes. The unique contours of Apsaras- the Divine nymphs of Devalok and Gandharvas-the heavenly musicians as illustrated in the Hindu mythology were introduced by the Buddhist monks and have been expansively depicted in these frescoes.

These Apsaras as depicted in these Chinese frescos stand in the Tribhangi stance or the S-Shape, having its postural relation with the Indian classical dance form of Odissi. In these early fresco paintings, the Apsaras have been shown wearing costumes of Indian origin.

These Apsaras were seen with long hair in barefoot; they have seen topless covered with jewelry, armlets, bracelets, and anklets. They wore colored drapes and wrapped free-flowing ribbons around their bodies. The lower part of the body was covered with short knee-length skirts or chinos.

These Apsaras in the cave paintings can be seen as having Greek, Roman, Gandharaian, Persian, Central Asian, and Indian influence. The multi-facet impact on the Chinese Apsaras added unique iconic features to the fresco Apsaras of Dunhuang.

The early Apsara figures illustrated in these caves are usually shown having a v-shape posture with a rigid and cumbersome body. These Apsaras looked much different from their Indian predecessors.

Instead of depicting the idealized female body, the early representations of Apsaras in the Dunhuang mural were muscular.

The Apsara figures during the period of Tang dynasty (618-904 CE) were naturalistic, vivid, and embodied Chinese perception of gorgeousness. Regarded as a high point in Chinese civilization and a golden age of cosmopolitan culture of China the Apsaras portrayed during this period display the pinnacle of Dunhuang art.

In nearly all the five hundred Mogao grottoes, there are more than two hundred caves that have flying Apsaras displaying diverse attitudes, full of spirit and energy. There are some Apsaras leaning against the fence and overlooking while some are free-flying.

There is a depiction of heroic King Kong and also of some gentle and dignified Bodhisattva. Distinct changes can be seen in these Apsaras almost in every dynasty during the thousand-year journey of their creation. All the dynasties had varied flying Apsara images that continued to evolve with the passage of time and history for a thousand years.

The Silk Route was a passage to trade and exchange silk, spices, indigo, precious gems, paper, and many other goods that were equally significant to those times. Besides trade and relocation, this route was also the path through which Buddhism traveled from India and spread throughout Central Asia.

The entry of Buddhism into China from India altered the visage of China. The Chinese landscape transformed forever with the creation of pagodas and monasteries and also with the fascinatingly exclusive airborne Apsaras embellishing them. The Apsaras had successfully made their way through the Silk Route to China.

Explore Apsaras series Part I, II, III , and IV

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.