The sun beats down on the battlefield, although it is lessening from the high it had hit earlier in the afternoon. In about an hour, it will be time for everybody to return to camp.

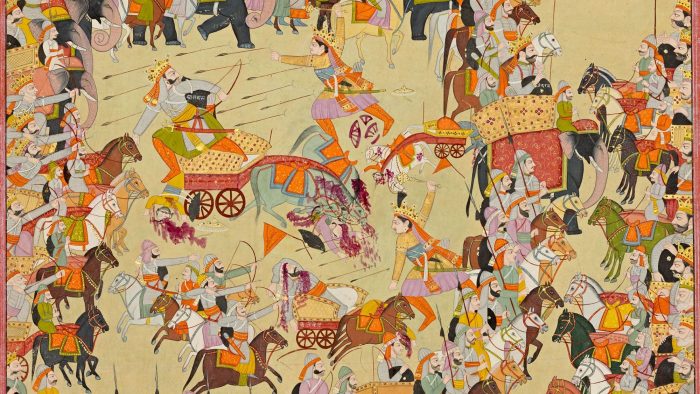

I look ahead of me and raise my sword, slamming it against the steel of the unnamed soldier before me. The force pushes him back, and he stumbles onto the ground. My charioteer steers away from him. He didn’t deserve such a death. The dust-covered horses reined to the chariot whinny just ahead, and it echoes in my ears, twice as loud as it should be thanks to the adrenaline making its way through my body.

Swords rise and fall in front of me in a never-ending repetition, creating patterns of light as the sunlight glints off the metal, dancing across my vision. Arrows shoot at me from the distance, but I duck, sidestep, and slice most of them out of the air. Some make their way through, but they hit me in the shoulder and some lightly graze my abdomen. Nothing serious, but then one comes fast, faster than I can nudge out of the air and knocks off my helmet. I can tell, just by the target, the speed, and the precision, that it was no accident – this was a master archer, maybe one of the greatest on the battlefield.

I look around. A white-bearded, elderly, but still strong man stares back at me and nods, ever so slightly. It’s Dronacharya. He taught my father and uncles, and I’ve heard so much about him, that even a gesture of approval can carry you to the sun and back.

Just as I’m floating in the sea of pleasure created by the small acknowledgement, a sharp pain shoots through my abdomen. A stray arrow, one I had not noticed before, had made its way through my admittedly lax guard, and shot into my stomach. My fingers shoot to the wound, trying desperately to fill in for the lack of a proper bandage. Crimson blood seeps through my fingers anyway, making its way through a chink in my armour, down my torso, onto my trousers in a gushing red rivulet.

I grit my teeth and mentally prepare myself for the battle ahead. There was still half an hour before there would be a ceasefire. If my uncles made it, then they would defeat everybody here and take me back. I’d see my father again, win his approval. The thought filled me with a sense of delight, however out of place the emotion seemed in the midst of a battle.

I raise my sword once again and make eye contact to my charioteer, who has turned around to glance at me in concern. He’s been steering for me my whole adult life, and we’d developed quite a bond. Very slowly, I nod and force a grin, signalling that I’m ready to go. He looks warily at me and offers me his own helmet as a replacement for my own. I shake my head and smile again, although this time it’s not forced. He places the helmet back on his head and turns around grabbing the reins and spurring the horses into action. I raise my sword higher and adjust my grip on the hilt. My shield, which was broken earlier in the day by a particularly skilled foot soldier, who’d just managed to turn it into a jagged crescent before I dispatched him, lifted higher as I adjusted it to cover as much of my body as possible.

I wipe a bead of sweat off my forehead and spare a glance down at my abdomen. The wound only seems to be worse – the blood flow is stronger every time I check. I haven’t been able to pull out the arrow yet – the exit could cause more damage, and I don’t think I can do that quite yet. The arrow might be the only thing preventing my insides from flooding out. I suppress a shudder, and, on a sixth sense, turn around just in time to see a sneaky warrior, who has climbed onto my chariot from his horse, swing his blade at my neck. I smile grimly and raise my sword to block it, and then quickly stabbing him in the chest. His non-sword arm was already severed, and he had multiple gaping lacerations – I was doing him a favour.

It was almost sunset. I highly doubted that my uncles were coming. They’d had over 4 hours to come to my aid, to make good on their promise, and they’d failed.

I’m going to die here. The realisation is crystal clear, dawning upon my mind and washing out everything else. My body moves like a machine, swiping, blocking and stabbing at everything that comes at me.

The mindset is gone as soon as it comes. Sensory input flows in at once from every direction informing about the movements and sounds of the battlefield. More than anything else, one thought comes to the front of my mind: my uncles.

I’d always relied on them, always trusted them just like my father. They’d promised they would be right behind me, right on my tail, because I was their nephew and they loved me, but at the end of the day, they’d sent me in here, knowing full well that I couldn’t get out and that they couldn’t get in. They’d sent me to my death, whether they knew it or not, hoping that I could take as many people down with me as I could. They’d been like fathers to me, but they weren’t here, and my father would be.

Again, I realise something – my father doesn’t know. Uncle Bheema had said in passing, almost casually that my father was in full support of this idea. That he trusted his brothers to take care of his son. I hadn’t thought it through at the time, but I realised that this was a risk my father would never take, and nor would my Uncle Krishna. There was no way either of them had been told. But at the time, I’d been too proud, too self-confident, too eager to prove myself. I’d thought I could do anything.

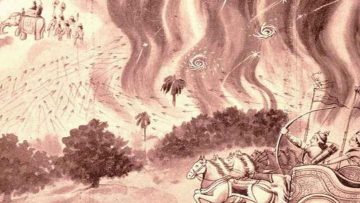

It was early evening, of the previous day. My uncles had just been informed of the formation that the Kauravas were planning for the next day: a chakravyuh. One of the most complicated and impregnable formations possible in warfare. But we had luck on our side. My father and Uncle Krishna were among the handful of people in the world who possessed the rare knowledge that would allow them to enter and exit the formidable arrangement. And so did I. To some extent.

It was while I was still in my mother’s womb. To humour her, my uncle, Krishna had asked her to accompany him on one of his many excursions across the land. She’d gladly agreed, and on the chariot ride, as a way to entertain her, my uncle had started explaining to her one of the most coveted military techniques – how to break the chakravyuh. She did not find it an interesting topic, and I doubt she remembers any of it now, but what they did not know was that I, her unborn child, was engrossed in every word. I strained to absorb every word he related, right up until he explained how to break the seventh and innermost layer of the chakravyuh. Right at that point, my uncle noticed that my mother had dozed off, and stopped explaining the technique, diverting his attention to the road instead.

But the information still remained with me. And when Uncle Yudhishtira heard about it, although I do not know where from, he immediately came to me to plead for my help in saving the honour of the Pandavas. None of them could break the chakravyuh, you see. They were not privy to that secret. And losing one’s honour was the worst possible disgrace. They could never show their faces again, on or off the battlefield. So naturally, I agreed.

The wound in my abdomen suddenly explodes with pain. An arrow has made it through yet again, striking a spot just shy of the previous wound. I groan again. Red spots cloud my vision.

I take a final deep breath, and straighten my back from my position, leaning against the flagpole in my chariot. Yes, I’m going to die today. I know it, as much as I know that the sun is going to rise tomorrow, and the battle is going to continue. I’m never going to see my father again. I’m never going to see my wife again, or my mother. I’m never going to get to hold my unborn child. But I’m going to do my best on this battlefield, so that they can survive, so that my child can grow up in this beautiful kingdom, knowing everything that I did as a child – knowing what it is like to have one father, but 6 father figures. Knowing what it is like to be loved by people who will put you before anything and everything else. Knowing what it is like to love and be loved.

Yes, I’m going to die. But I’m going to take as many people as I can with me. Until my last breath, I’m going to follow a kshatriya’s dharma. I’m going to fight as a warrior, and die as one.

(Editor’s Note- This piece is a fictional account of Abhimanyu’s last battle written by a young adult.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.