There is No New Story

While other disciplines of ancient art like sculpture, architecture, or painting seldom bore the name of the artist, literature is a discipline in which the creator’s name has been relatively more present. In Greece, the three greatest of the ancient playwrights – Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles – were all known by their names. The same was true about poets like Homer or Ovid.

In India the playwrights were famous by their names too, the most popular name being of course Kalidasa. About others like Bhasa no clear historical details are available. Some traditions say that there is little indication that they were persons or just honorific titles for a tradition or a sect.

In literature the artist disappeared not in name, but in content

Most of these Indian and Greet playwrights and poets did not claim to invent new stories and novel plots. They just took incidents out of the great epics or the great Puranic stories and played on a particular aspect in the contemporary idiom to enthrall their audience.

Kalidasa used the Mahabharata story as the plot of Abhijnana Shakuntalam. Similarly, Bhasa based six of his plays on the Mahabharata focusing on various different incidents of the Mahabharata, the most famous being Urubhanga where the killing of Duryodhana at the hands of Bheema is described in heart-rending detail. He also based three plays on the Ramayana. Bhavabhuti based his plays on the themes from the Ramayana too.

Post-Renaissance European literature was no different. Though playwrights were very famous by their own names, they seldom created their own stories, at least in the genre of tragedy. Most of the stories and plots of Shakespeare are picked from the classical myths. Similarly, the story of Faust is played on by various great playwrights.

Only in comedy, we see that the playwright was coming into full vogue. The comedies were considered lighter in vein, less serious, and less exalted, just like in ancient Greece and it is here that we see the imprint of the playwright slowly emerging. Though this was true of ancient Greece too and Aristophanes also created new ‘plots’ and ‘stories’ with his extremely irreverent comedies.

India had always steered clear of the very restricting division of comedy vs. tragedy that is the benchmark in Western classical literature. No true tragedies exist in Sanskrit theatre and till date Indians cannot comprehend the point of an absolute tragedy. Teaching by catharsis, the point of the Greek tragedy, is beyond the understanding of an Indian.

To come back to the point, even the pagan West understood that ‘there can be no new story under the sky’ and playwrights always played on the familiar themes to which everyone could identify with. Except for comedies there was no claim of ‘creating something new’. Only artistic expression was important. Even the comedies fed on making fun of some classical themes and rituals accepted upon by all.

It was commonly understood in India that retelling the classical story was neither plagiarism nor blind copying. Goswami Tulsidas has never been ‘condemned’ for his ‘lack of originality’. He took the classical story and not only did he tell it in the vernacular, but also added a fresh way of looking. He made the entire story more devotional. He took a story, relived it, and made it his own by meditation, my inner experience, and by divine contemplation. As Coomaraswamy says:

“A copyright could not have been conceived where it was well understood that there can be no property in ideas, which are his who entertains them: whoever thus makes an idea his own is working originally, bringing forth from an immediate source within himself, regardless of how many times the same idea may have been expressed by others before or around him.” (Coomaraswamy 112-113)

This was largely the trend in all traditional societies until the dawn of the modern West. The celebration of classical stories and archetypal myths came to an end in the West with the advent of a new medium – the novel.

The Introduction of the Author

By the eighteenth century, the novel emerged as a primary mode of literature in the West. And with the novel, the author is truly born. The novel, long-winding and detailed, focused not just on the heroic and the exemplary but also on the mundane and the banal. And it is precisely this focus on the mundane and the banal which made it famous.

With the proliferation of the printing press and the elevation of the secular life where literature was taken as a refined entertainment, the novel emerged as a means to entertain primarily the ladies of the higher class.

These petite women of the elite class were divested of the daily chores that the lower class was engaged in and had plenty of free time to acquire greater literary and artistic skills. Reading novels in those days was a means to do that: to gain skills and knowledge about the world.

This was not just true about Jane Austen but also about Charles Dickens. The working class seldom had the education, taste or money to indulge in such pleasures as reading a novel. And there was hardly a middle class in this era.

The Industrial Revolution was just starting. Novel reading was the exclusive realm of the elite. Unlike drama, the novel remained confined to the elite of the West.

On one hand these readers wanted to read about the life with which they were familiar with. This is why the novels of Jane Austen were that famous. On the other hand, they also wanted to know what was going on in the life of the less fortunate, the hoi polloi.

This is the reason that Charles Dickens was so famous in these circles. His stories about the seamier side of London; about the underbelly of the country, were something which entertained the elite too. It was only in later centuries that his works became more famous in the general public.

On the other side of the continent, the Russian salons of St. Petersburg would not be complete without reading or the discussion about The Captain’s Daughter or Eugene Onegin by their greatest poet Aleksandr Pushkin.

The environment was infectious. Growing up in balls and parties like this, Lev Tolstoy created some of the greatest gems: War and Peace and Anna Karenina. War and Peace are often claimed to be the greatest novel ever written if there can be such a list or comparison.

These salons were mainly run by the most famous and prosperous women of the elite society of St. Petersburg. It was considered an obligation of the rich women to throw soirees, or parties of this kind where every influential personality from politics, arts, literature, and music would be invited.

In the pre-mass media, pre-mass publishing, and pre-internet era, these intellectual salons were the only places where young, poets, novelists, musicians, and artists could show off their talent. These salons made or broke artists and poets.

Getting invited to these ‘art scenes’ of the days was very important. The ladies who ran these salons may not necessarily be of great taste but they completed their social obligation in throwing off these soirees and inviting all the great artists of the day. These salons were known by the names of these ‘socialites’.

The poets, novelists, and artists visiting these balls and parties created some of the greatest works ever created analyzing human behavior in all its minutiae, both good and bad.

And even though their readership may be limited to one gender and to the elite during their times, they have given us gems which are quintessentially classical – independent of time and space. They are truly universal.

The breathtaking variety of aesthetic stories that the world had the luck to witness during the late half of the 18th and the 19th centuries is something to cherish. Dickens, Austen, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Chekhov, Turgenev, Poe, Melville, London, Twain, Proust, Flaubert, Maupassant, Saki, Akutagawa, etc. are just some of the very famous ones.

The Degeneration Sets In

Not before long, the most important stories were told. The national characters were written about. The stories were exhausted. The narratives had taken all the plausible twists that they could take. Nineteenth-century like much else in the West was the heyday of the novel.

Starting out at various times from early 18th century most of the great nations of the West: Britain, Russia, America, France, Germany, Italy, Spain etc. had exhausted themselves by the closing of the 19th century.

The early 20th century saw some great works, but the great literary flowering of the modern West was already on a decline.

V S Naipaul has remarked that much written cultures have their own problems. It is hard to find a ‘new theme’, a ‘new story’ in a culture which has produced giants like Austen and Dickens. One would do well to remember that in a classical world this would not be a problem as no author, dramatist or artist was under pressure to create ‘something new’.

The old stories had to be told in the new idiom. The universal archetypes had to be delivered in contemporary language. With the advent of the novel as the primary vehicle of literature in the 18th century, this had changed. With the focus on the banal and the mundane, the authors were after finding a new story. This led them to a race to find ever novel ways to entertain their audience.

The search soon degenerated into a search for the strange. Like in other disciplines, the good was replaced by the strange. The old stories had to be told in the new idiom. The universal archetypes had to be delivered in contemporary language. With the advent of the novel as the primary vehicle of literature in the 18th century this had changed. With the focus on the banal and the mundane, the authors were after finding a new story. This led them on a race to find ever novel ways to entertain their audience.

The search soon degenerated into a search for the strange. Like in other disciplines, the good was replaced by the strange. At first, the experiments were limited to the stories. Then the narrative style was experimented with too. At last even language was not left alone. Deconstruction is a process not stopped easily.

One reason for the crisis in literature was the advent of the cinema. The cinema had taken the wind out of both the theatre and the novel. The fast-moving plot of the cinema could hardly be matched in the theatre.

The action that could be shown in cinema was out of the question on a stage. And the emotions became subtler too. What took poets many pages to describe, for example, a great beautiful landscape, would be shown in five seconds without any words in cinema.

Thus the drama and the novel were left to do what the cinema couldn’t do. Even then they could have settled on their own if not for some postmodernist theories that started floating during the same decades.

For the 20th century saw the rise of post-modernism, post-structuralism, and deconstruction in which many universal props of the traditional novel and ancient theatre were destroyed. The post-modernists claimed that there is no objective truth and thus no good or bad.

As a result out went the hero and the heroism from the play and the novel. The deconstructionists claimed that the world is unreal and our eyes, our minds, and our senses lie to us. They also claimed that every story is a narrative presenting one point of view, none of which is correct and none of which can be conclusively proved wrong.

The traditional drama or the novel had a hero and a villain. Its author had very clear ideas about good and bad. The plot was central to the story, although not paramount. The language was refined and lofty. Uncertainty was occasional and little. There was a definite conclusion and a takeaway message.

The postmodern theories destroyed all of these conventions, breaking all of the legs on which a traditional drama or novel would stand. The result was the modern novel with no noble hero, not even a sympathetic common man, no clear idea of good or bad, no plot, no story, no chronology, and no definite conclusion or message.

Deconstructing the Novel

One of the greatest ‘agents of change’, the foremost of avante garde writers of the early 20th century was James Joyce. He was undoubtedly one of the greatest literary minds ever born. Dubliners, one of his early works, is one of the most beautiful odes to a place. It is the story of a place, more than its people. It is something authors wanting to write about a place dream to achieve.

But it was James Joyce who, because of his talent and not despite of it, deconstructed the genre of the novel. Ulysses, his first such experimental work, tells the story in one day in the life of Stephen Dedalus. The story is allegorical. The plot is confusing and it takes many readings and much supplementary reading to make sense of it.

Soon the plot completely disappeared from the novel. Other writers started emulating Joyce as he was a literary giant of his age. With magical realism, all the sacred principles of good old storytelling were abandoned.

Magical realism was an understandable medium for the South Americans who built upon their experience of shamans and magical stories of the tribes. But the magical realism which seeped out to the rest of the world just destroyed the discipline.

Led by Joyce, a new technique called Stream of Consciousness was becoming very famous in the West. This style meant that the writer has to put on paper whatever came to his mind without editing, in the rawest form. He was not even allowed to organize his thoughts or even his language. For any ‘editing’ or ‘organizing’ will create a narrative which the authors dreaded like the plague.

Jacques Derrida along with Roland Barthes meanwhile was peddling that ‘writing has no meaning’, and ‘there is no inherent meaning in language’ and that ‘meaning is constructed by the reader as he goes along’.

This intellectualization of the art of storytelling resulted in the destruction of the very tools of writing, of creating literature. The degradation was quick. In Finnegans Wake, a later work of Joyce, we see that the language itself is destroyed.

Finnegans Wake is classed as a novel but it can be read forwards and backwards, from the beginning, from the middle, and starting from the last; which means that it is essentially meaningless nonsense. And I mean it literally.

Many of its pages don’t have paragraphs or proper sentences and sometimes not even words. Sometimes entire pages are filled with “..rattttttttttttttttshhhhhhhhhh…” and so. The author did not have to edit it, they said! It had to be raw they said!

The postmodernists and deconstructionists argued that not only the story, the plot, the narrative, but even language had to be deconstructed for staying true to reality, as even language is a human construct.

This is factually untrue. Language has deeper evolutionary and biological roots as proved by cognitive scientists and neurobiologists in the 21st century. But science is seldom the strong point of ideologues. As a result: not just the product, that is literature, but even the medium, that is language was also destroyed.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

In drama parallel strains were evolving. The Theatre of the Absurd had been deconstructing some of the fundamentals of the art of drama. Since they said that language is a human construct and it is impossible to convey your feelings to one another, the plays of this genre were filled with nonsequiturs where two actors would talk incoherently about inconsequential and unrelated things without making any sense.

The entire point of the play would be to convey the claimed irrationality of life, the illogic of language, and the meaninglessness of drama.

Some great artists like Samuel Beckett managed to wring one or two good pieces like Waiting for the Godot, but the genre in general was thoroughly deconstructed from within with the destruction of dialogue, action and plot.

Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard and Jean Genet were some of the hacks in this new industry of Theatre of the Absurd.

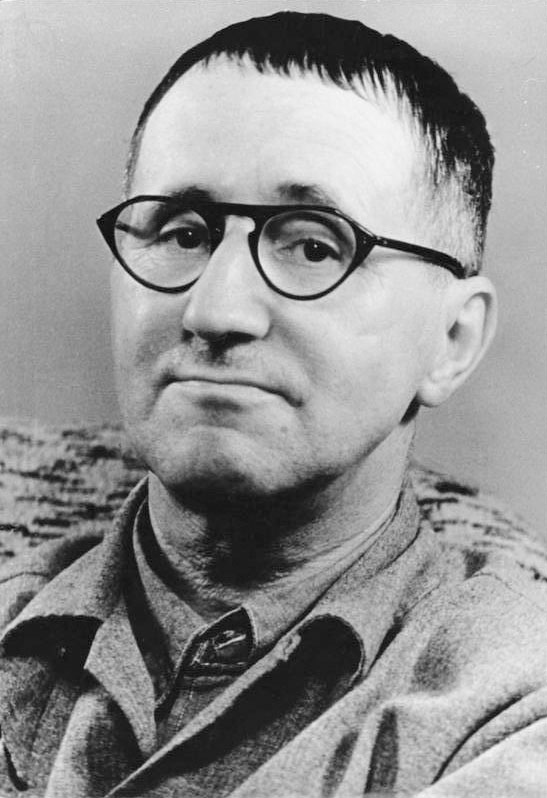

Bertolt Brecht the Marxist dramatist and ideologue from Germany deconstructed drama from the other end. The Fourth Wall is a convention in the drama. In any theatre, the stage has generally three walls behind and on the two sides of the artist.

The front is obviously open for the audience to see what is happening on the stage. However, the artists behave as if the audience is not present and as if there is an invisible fourth wall. They don’t notice the audience and this is called ‘maintaining the fourth wall’.

Brecht argued that the drama is unreal and the audience shouldn’t be misled to believe that it is real and hence the fundamental stage ethic of the artist – to maintain the fourth wall – has to be broken deliberately many times throughout the drama.

He said that it was necessary to make the audience realize that the drama was not real. In his plays, the actors would deliberately converse with the audience in between and remark upon what was happening in the audience. It was one step further in the deconstruction of the traditional play.

The poetry saw the same degeneration. The paucity of space here does not give full freedom to remark upon this genre here, but suffice to say that what started as individual innovation in late medieval times when Shakespeare started using blank verse profusely got degenerated in modern times into free verse. In blank verse, rhyming was abandoned in favor of rhythm, but by modern times even rhythm was abandoned.

Any notion that poetry is meant to be recited was also abandoned and just about anything started to be passed off as poetry. Any tinkering would qualify as artistic innovation. All of this started off with the belief that the individual can create art without any divine inspiration; that authors can create new stories.

The humility that goes with this traditional worldview that the artist is just a conduit for expressing the glimpses of the Ultimate Truth; and that higher truths just flow through him with divine grace was the first casualty upon the introduction of the author.

At first, it resulted in an explosion of creativity. But soon the usual avenues were exhausted and the personality of the author with all its eccentricities and idiosyncrasies started imposing too much upon his art.

The author was becoming too imposing upon literature. As a result, the postmodernist era saw revolts ‘against the author’, but ironically they made the idiosyncratic imprint of the author even more significant upon his.

Most of the modern literature has no plot, no story, no hero, no concept of good and bad, no chronology, and no coherent dialogue. They are at best, confused, and confusing parallel narratives delivered in the inebriated state of the narrator, not necessarily making sense in either time or place. The reader truly can make of them whatever he wants to.

The Wisdom of India

In India under the aegis of Sanatana Dharma, the agency of the author as a vessel and as a conduit was always recognized and thus we always hear the names of the dramatists, poets and authors but not much attention is given to their personalities. Their stories and their message are considered more important than their personality.

It was also commonly agreed upon that a piece of great art is created only with divine inspiration and not through the individual innovation of the author or the poet. This is evident in almost all epics and poems where the agency and authority of Shri Ganesha or some other deity is always invoked.

The story is also said to be only ‘heard’ by the poet from some divine sage or a primary deity. No claim of originality is made. The idea of ‘genius’ in the modern sense was missing in ancient India. What was valued was the effort to approximate most to the ideals of the Sanatana civilization. Coomaraswamy once again explains:

“For what is a masterpiece? Not as commonly supposed an individual flight of the imagination, beyond the common reach in its own time and place and rather for posterity than for ourselves; but by definition, a piece of work done by an apprentice at the close of his apprenticeship and by which he proves his right to be admitted into the full membership of a guild, or as we should now say trade union, as a master workman. The masterpiece is simply the proof of competence expected and demanded from every graduate artist…” (Coomaraswamy 98-99)

The sanctity of the language is also maintained. The Sanatana tradition has always maintained that reality is far beyond the powers of the description of any language, even Sanskrit. Even Sanskrit is said to be only the Vaikhari form of language, which has three other, deeper planes of existence.

The first arises from the primal source, from the Universal Consciousness and in this form it is inexpressible. This stage is called Para. It is then visualized as an image or a picture which is the stage of Pashyanti. It then goes to another stage called Madhyama where it is verbalized but unspoken. When it is uttered in human language it is called Vaikhari and even in this last stage it is changed and is not expressed as is thought in Madhyama.

Having maintained this, the Rishis of India recognized that even in Vaikhari it was necessary to convey the divine message in whatever form possible. And thus the Vaikhari form of language was completely mastered. Sanskrit was refined as much as a human language can be refined and the spiritual and eternal message is more easily conveyed in Sanskrit than in other languages.

The point is that that the tools of expression, that is language, were never deconstructed in India. Along with recognizing that the Ultimate Truth is inexpressible in human language, ways of reaching that Truth was indicated as much as possible in human language.

In the West, starting with Christianity, it was claimed that Ultimate Truth is expressible in human language and was expressed once and for all in the Bible. When the Bible was proved false the West went in the opposite direction. Now they started claiming that no fact can be expressed in any language, however banal or mundane the fact is.

Ever going to one extreme of the pendulum Sanatana Dharma never went to another in reaction. But the West sadly did. This in a way was a result of the Christian insistence that the Ultimate Truth can be expressed completely in human words. By doing that they took divine inspiration out of any artist’s work.

Once that had happened, revolts started coming and in the post-Renaissance world, the author started overpowering literature and gradually degenerated to the current state. At the core of this are the introduction of the author, the introduction of the individual agency, and the claim that something new can be created by sheer intellectual innovation.

REFERENCES

1. Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre. Blooomsbury Academic, 2018.

2. Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art. Munshiram Manoharlal, 2008.

3. Figes, Orlando. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. Penguin UK, 2003.

4. Gupt, Bharat. Dramatic Concepts Greek and Indian: Study in Poetics and the Natyasastra. D K Printworld, 1995.

5. Naipaul, V. S. Reading, and Writing: A Personal Account. New York Review Books, 2000.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.