The Traditional Artist

Music is most universally popular of all arts and yet one of the most difficult to master. In music too, the ideas that have been discussed in ‘The Artist in the Art’ series have led to a general degradation. Before we go into the trends that took western music to its present situation let us discuss just one brief situation with Indian music.

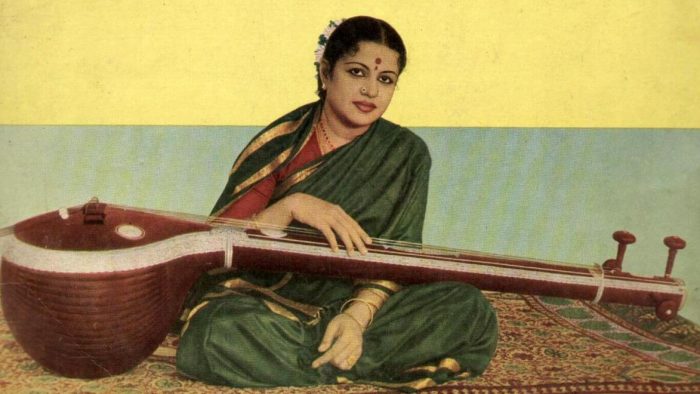

Music is an art form in India in which the entire tradition continues even today, though in a much reduced capacity. But it is still vibrant to produce great artists like M. S. Subbulakshmi.

She is one of the most famous artists of her time. But she is not famous for creating her own songs, her own stotras, or her own symphonies. Rather she is famous for rendering in her magical voice, some of the greatest of stotras, sahasranams, and suprabhatams that were created by the great rishis of ancient India.

As an artist, she was much respected and her fame was international. And yet she was not famous for ‘patenting’ some technique of her own, or for creating a music album which ‘discovered something new under the sky’. She excelled in rendering the great creations of her ancestors.

The same is true about other artists too. Pandit Jasraj lends his magical voice to the traditional Ragas, but does not violate them. He creates new bhajans and new songs, but not new ragas. Kishori Amonikar is most famous for rendering the symphonies of Meerabai in her magical voice.

In the north there are individual imprints on musical creations but these imprints too are known by the name of the tradition of the particular gharana of music, rather than certain individuals. Even in these innovations the basic rules of music laid down in the Natyashastra and other great musical texts of the middle ages are not violated. The traditional idea of music is confirmed in all the ‘new creations’.

This does not mean that the artist did not have creative freedom and he could only create music in the strict confines of canonical rules. Dr. Bharat Gupt, one of the foremost authorities on music, drama, and fine arts in contemporary India says that the shastras in India provide a formula or a template to create art. It is upon the artist to innovate and create particular pieces of art based on these formulas or templates.

These templates are based upon the fundamental rules of aesthetics as given by Bharat Muni in the Natyashastra. Thus contrary to some modern opinions, classical art does not restrict an artist from innovation or creativity but provides a template based on some universal rules of aesthetics but leaving ample room for innovation.

That being said the artistic ethos of India fostered a climate where striving up to the standards of the ancients was considered an ideal. There was much artistic creativity on individual level, but the artist himself was encouraged to meditate and lose himself in the Supreme Consciousness and it was believed that real music and real innovation came from the inspiration of the Divine, from the touch of the Supreme Consciousness in various states of meditation. Individual innovation devoid of divine inspiration was considered incapable of touching the heights necessary to create great music.

Dissonance and the Inversion of Classical Ideas

India was not alone in believing that individual innovation has to be blessed with divine inspiration to create great art. This was the case with all ancient traditions all over the world: in the East in China or Japan, or in the West in Greece and Rome.

In the case of music, it was sometime during the Enlightenment that this idea was abandoned and personal innovation started overpowering divine inspiration.

Though the break with the traditional idea of creating music had been done in the Enlightenment it was in the early 20th century that radical developments were made which ‘rebelled’ against the traditional idea of music.

Igor Stravinsky is considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, credited with many new inventions and remaining at the forefront of the avant garde movements in music that had become common in the early 20th century. (Tommasini)

In music, like in everything else, ideology had come to pervade by the early 20th century. In the beginning of the 20th century, Stravinsky, like many of his colleagues, was experimenting with new techniques and new inspirations for creating an entirely different kind of music.

The days of the Narodnik Movement were not completely a matter of the past. The movement had exhorted the students of cities to go to the villages of Mother Russia to discover new themes and get inspired by the folk culture.

In music, this theme persisted longer than other areas. Stravinsky studied folk music for some time and around 1913 he came up with one of the most revolutionary pieces in western music – The Rite of Spring. It was a ballet and orchestral concert work which was claimed to be based upon folk music.

In this ballet, he experimented with various technicalities of musical wizardry, including tonality, metre, and stress, but the most revolutionary and shocking of all was his use of dissonance.

Dissonance, as the word suggests, is a lack of harmony among musical notes. It is something which the composers, at least before Stravinsky, usually shied away from. Music had to have consonance which means harmony among musical notes, so the different instruments flow together to create a melodious harmony.

Stravinsky stood this idea on its head. What Bertolt Brecht did in drama, he did in music. He refused to go by the core practices of his discipline. Like Wassily Kandinsky in painting, he did not just want to experiment in art, but also with the crafts of music. He wanted the musician to be ‘completely free’, even of all musical discipline.

Consonance was considered the basic discipline in music. If your music wasn’t consonant, then it wasn’t considered imperfect and faulty. Stravinsky violated that basic rule and gave the idea of ‘dissonance in music’.

The result was, as expected, horrible. The audience first described the resulting ballet as nothing more than a ‘screeching riot’. And it was a natural reaction. However, like all things ideologically fashionable, the public abhorrence of the Rite of Spring was considered as a proof of artistic greatness by all the avant garde musicians and artists of the age, particularly in France and gradually the idea of ‘dissonance’ picked up.

It was the intellectual climate of Europe at the time, in which different disciplines of arts, literature, music, painting, and architecture were in the process of self-destruction. They were experimenting with the very crafts of the discipline, in a bid to search something new.

And after a while, this search led them to deconstruct what had been created by the ancestors. Stravinsky’s dissonance was a result of this urge. Music caught on to this urge later on, but with Stravinsky, this urge for degradation just exploded.

Stravinsky was followed by Bela Bartok and Maurice Ravel. Bartok’s singular contribution was to break down the diatonic system of harmony in music. For three hundred years, musical composers before Bartok had used the diatonic system which according to a broad agreement created harmony in music. But since the goal in music was now to deconstruct harmony, Bartok disavowed the use of diatonic harmony in his music.

Maurice Ravel created various great and truly beautiful pieces but flowing with the fashion of his age he played with various traditional concepts. In most musical pieces in the preceding three hundred years, the convention was to develop a piece until it reaches a climax. Ravel instead created pieces which replaced development with repetition.

At the start of the 20th century a group of avant garde artists was created called Les Apaches or ‘The Hooligans’. By self-expression its members were ‘artistic outcasts’. One of its star members was Claude Debussy. He was a musical genius who loved to play with traditional ideas. In Ravel’s own words Debussy’s “genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely…” (Orenstein 33)

The point to note here is that he was appreciated more for his ‘creation of his own laws’ than good pieces of music. ‘Innovation’, no matter how strange or unpleasant to the ear it was, had started to be prized more than the actual quality of music.

Ideology and Politics Overcome Musical Tradition

The trend to violate the most classical rules of music had started. Composers started creating music based on dissonance, ambiguity and atonality.

All of these new ‘techniques’ were actually considered faults in classical music. But modern composers turned them into bedrocks of their musical ‘innovations’. The results were more often than not were unpleasant and not pleasing to the ear but ‘judging music’ based on classical ideas was already a backward thing to do in the 1950s and 60s musical scene.

Just like a modern painting could not be ‘judged’ for the ‘beauty is created in the act of seeing’ and judgment was considered plebeian or downright evil, so in music, what was prized was the strangeness of a musical piece and not its ability to please the audience. Ideology had triumphed aesthetics in music too.

Once again, there is nothing wrong in innovation but in all classical theories of art there is a boundary which is never to be crossed in search for ‘innovation’. There are some universals which are never violated. Artistic freedom is never absolute and there are some universal laws and rules are always to be followed.

Drawing this boundary is necessary because once the theoretical need for creating such a boundary is lifted, the floodgates of directionless, meaningless and aimless ‘innovation’ open and soon art degenerates into something which is indistinguishable from nonsense.

When these ideas of aimless, unguided and non-directional ‘innovation’ were introduced in music they resulted in pieces which were hardly distinguishable from noise. A classical definition of pitch, one of the fundamental units of denoting music is that it should have a frequency that is clear and stable enough to distinguish it from noise.

I need not pitch in here to say that this rule was also regularly violated in ‘modern music’. Is it any wonder that what resulted was scarcely better than ‘noise’?

In music this erasure of boundaries meant that melodious and harmonious music was the farthest thing to be expected from the avant garde artists.

Musician Nikhil Rao tells us that this trend in ‘musical innovation’ degenerated to a point where composers were recording things like running bicycles, slamming doors, and other assorted screeching noises.

Barring a few exceptions who still produce good music on classical lines, classical music died a death in the 1950s and 60s with these avant garde ‘innovations’. In the words of Alex Ross:

“Within the classical composition, meanwhile, activity on the outer edges had further blurred the job description. By the early fifties, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry were creating collages that incorporated recordings of train engines and other urban sounds; Karlheinz Stockhausen was assisting in the invention of synthesized sound; John Cage was convening ensembles of radios. By century’s end, a composer could be a performance artist, a sound artist, a laptop conceptualist, or an avant-garde d.j…” (Ross, The New Yorker)

Much of this ‘musical innovation’ resulted after the Second World War ended. The two world wars massively disturbed music in traditional Europe and even though modern music had made great headway in pre-war Europe, in post-war America, a melting pot of musicians and artists was created in which traditional imprints disappeared and innovation became more and more important.

The primary purpose of modern and postmodern music was to shock the audience and not to entertain and elevate them with classical musical principles of melody and harmony. Arnold Schoenberg, a genius, was a master of creating atonal music in which traditional boundaries were regularly broken.

Like Brecht’s dictum that the fourth wall in theatre had to be regularly broken down, many of Schoenberg’s compositions required him to come out of singing and music, and engage in plain talking for a while before going back to singing.

A favorite trope of these avant garde artists was to use classical musical instruments in unconventional ways. Breaking convention, the greatest cliché of modern life was practiced to the hilt by these modern composers. John Cage, a very influential modern American composer, would often insert erasers, screws, and nails between the strings of the piano to distort the sounds and create new if bizarre and even jarring effects.

The aim is to discomfort the audience and ‘shock them out of musical conventions’. The means, more often than not, is to deliberately create horrifying and harsh music, which can seldom be differentiated from noise. Commenting upon the neo-modernist music of Brian Ferneyhough musical historian Rutherford-Johnson says:

“The way Ferneyhough deliberately overpacks his music with information, starting and restarting it every few seconds to create a perceptual overload, thwarts the memory’s ability to create a meaningful structure… Time after time, what we have just heard is pushed into the background by what follows next.” (Rutherford-John 177)

The reader would recall the article “The Author in Literature”, where James Joyce lead the movement of ‘Stream of Consciousness’, a writing style where the author ‘does not edit’ anything that comes to his mind and keeps writing continuously without ever paying attention to meaning, chronology, plot, and even grammar, syntax or spelling. Many pages in the ‘masterpiece’ of Stream of Consciousness writing novel Finnegan’s’ Wake are filled with gibberish like ‘ratttttttttttt…shhhhhhhhhhhh…hottttttttttttttoooooooooooooooooooo…’

Similarly, in music, the idea of Chance Music was floated. In this ‘technique’ no attention was paid to any deliberate composition. All the rules of compositions were of course thrown out the window. All aspects of music including composition and performance were left to chance. The most famous piece of ‘chance music’ is the composition ‘4’33’.

Calling it composition would be a contradiction in terms for it does not involve any music at all. In its ‘performance’ the audience sat staring at a non-playing stage and the ‘sound of the hall’ or in plain words, the noise of the audience was considered a ‘multi-movement’ composition!

Then there was Electronic Music in which composers like Edgard Varese actually synthesized new sounds using electronic instruments. Great genius and mathematician Charles Babbitt created computer-based musical pieces with such precise details that it can only be played by a computer and never by a human being. Computer Music claimed to ‘liberate music’ from human follies. Believe it or not but Noise Music is also a genre in the postmodernist musical scene.

It is not a wonder that this resulted in the death of classical music. Popular music on the other hand got a great fillip during the mid-20th century. Various musical movements and trends like rock, jazz, rap, and blues replaced classical music. But these movements did not escape the destructive tendency of postmodern music either. No rules and no holds barred ‘compositions’ became the norm. It was increasingly rare to find one musician creating good music consistently.

There was no emphasis on the learning of crafts or developing skills. Music was increasingly considered an ‘attitude’ rather than a craft or an art. All one had to do was adopt clothes, habits, and attitudes of the lifestyle of musicians, whatever it was. Knowing music and learning to play instruments was considered a secondary requirement if it was considered important at all.

Ideology became the prime requirement in music too. ‘Rebelling against tradition’ became the pre-eminent requirement of movements like punk rock. Just like Dadaism, the goal here was to keep destroying the tradition whatever it was. There was no central idea, no essence in these ‘musical movements’ if we can call them that. The only idea in these ‘musical movements’ was to keep destroying the traditional idea of music.

The modern music creates some really good pieces every now and then. But it is mostly due to accident. Bad musicians sometimes hit upon good numbers. Even good musicians with artistic ability suffer, because increasingly music schools and universities discourage the learning of skill and crafts and instead pay attention towards making ideological and political statements through music.

Prophetic Monotheism and the Disappearance of the Sacred Idea of Music

One of the greatest victories of Prophetic Monotheism is that gradually over two millennia it managed to overwhelm every aspect of human culture with ideological fashions. Music did not survive this onslaught either. The effect of Prophetic Monotheism on music was subtle and indirect, but it was there. In order to understand that first we need to understand how music remained intact in India.

India too witnesses all the modern movements in music like jazz, pop, rap, rock, etc. But in classical music, traditions which are millennia old still continue. Most of the classical music in India still follows most of the universal guidelines that were given in first the Natyashastra and then various other musical masterpieces like Sangeet Ratnakara.

What kept Indian Classical Music composed and together as a tradition was its continued focus on the spiritual goal in all musical compositions. No matter the direction from which Indian classical music is approached the divine never disappears completely from it.

This is truer about Carnatic music which became the refuge of Indian classical music and this tradition continued almost untouched till modern times.

Hindustani music in the north received some inputs during the Mughal era, but the influence was mainly in the modification of some musical instruments and not so much in the approach of music which is mostly full of bhakti and jnana.

It is the spiritual core which was eliminated in Western classical music once Christianity triumphed over Europe. At first, music remained melodious and harmonious if not meaningful in the sense of uplifting and leading towards the ultimate truth, but by the time of the Enlightenment degeneration was setting in and in the post-war West it altogether degenerated into noise.

The original reason behind the disappearance of the spiritual core was the imposition of Christianity over Europe and the destruction of the pagan culture. Once the divine disappeared from music, the pagan trends continued in the service of the church for some millennia but gradually and continuously lost their purpose.

In the Orthodox Church in the east, singing and chanting was retained and as a result they still retain an imprint of their own and despite the Christian theology this branch of church music still retains some spiritual core.

In the west, music was successively de-spiritualized. By the time of the Protestantism music was almost completely banished in favor of prayers. As a result, there was an explosion of beautiful and creative music in the secular domain which originally produced great masters whose symphonies are still as fresh as ever.

But with this secularization of music and the disappearance of the divine from the music resulted in a trend which we are now all familiar with. The introduction of the individual musician and the removal of the divine in the music led to a search for the ever new and the ever strange and the ‘classical music’ went down a path which ended in recording screeching noises of doors, of running bicycles, and creating ‘multi-movement’ music where audience’s chatter was considered live music.

References

- Orenstein, Arbie. Ravel: Man and Musician. Mineola. US Dover, 1991.

- Ross, Alex. “The Sounds of the Music in the Twenty-First Century”. The New Yorker. August 27, 2018 Issue.

- Rutherford-John, Tim. Music after the Fall – Modern Composition and Culture since 1989. University of California Press, 2017. p. 177.

- Tommasini, Anthony. “The Art of Setting the Sense on Edge”. The New Yorker. May 30, 2014.

Explore Part I, II, III, and IV

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.