M.S. Subbulakshmi, India’s much loved musician, embodied all that is great about India, and she showed us that one does not have to be apologetic about anything Indian.

As we reflect on her stature and achievement, it is also perhaps needed in many ways to make sure we testify to and reclaim the sheer magnificence, significance and glory of both, rescuing her legacy from a diminishment to which a certain discourse would like to politely or not so politely consign her, using disingenuously everything from feminism and modernism, to even, rather ironically, classicism.

In the mid-twentieth century, as her voice found its way into venues where only politics had held sway earlier, she was handpicked by the national leaders of pre-Independence India to be the voice of the country.

In a sense, she became the symbol of India’s nascent soft power, defined as the ability of a country to influence and appeal to others because of its culture and its values.

Dharma to M.S. Subbulakshmi meant the eternal principles of moral and spiritual advancement. In her speech at the Music Academy in 1969, she stressed that in the past, the creativity of India expressed itself mainly and dominantly in the sphere of Bhakti. Bhakti and music in India, to her, could be a creative force of integration and stability.

At the turn of the 20th century, just a few decades before her birth, Swami Vivekananda had said that there is one all dominating principle manifesting itself in the life of each nation. “In each nation, as in music, there is a main note, a central theme, upon which all others turn. Each nation has a theme, everything else is secondary. India’s theme is Dharma.” Vivekananda was the one who raised the clarion call of not just the strong Indian, but the unapologetic one.

M.S. Subbulakshmi was the first musician to win the Magsaysay award, a portent of all the great commendations that were to come her way, culminating with the Bharat Ratna. Her Magsaysay award citation begins with the lines… “Exacting purists acknowledge Srimati M.S. SUBBULAKSHMI as the leading exponent of classical and semi-classical songs in the Karnataka tradition of South India.”

Surely, these words had not been uttered lightly, and those who would question her skills and accomplishment in the realms of the most rigorously classical, should take pause. In her own times, it is her supposed capitulation to populism with her popular thukdas and bhakti rendering, not to mention her early films that was one bone of contention. Those threads of criticism have persisted, added to a superficial lamenting of her supposed inability to achieve her full potential because of the constraints imposed by a conservative and patriarchal society.

T T Krishnamachari, one of the founders of the Music Academy called hers the ‘Voice of the Century’, and she was certainly that. The sheer beauty of her voice itself, which is indeed so much like the clear, imposing ring of the Veena, was one of her greatest assets, which she put to good use in full measure.

But she was more than her voice, and peers in her inner circle have attested to her disappointment whenever she was praised only for it. The first woman to be awarded the Sangita Kalanidhi award by the Music Academy in 1968, in her speech M.S. Subbulakshmi attested to the importance of rigorous training and the need to distinguish between rote learning and theoretical knowledge and assiduous practice and voice culture which will lead to the “blossoming of the art of music.”

In a beautiful passage where she talks about the Veena, the depth of her relationship to what the art of music is all about comes ringing through. “The manner in which the swaras are woven into the various ragas in our Karnatic music can be best studied by playing them on the vina…It is only the vina that can best demonstrate the nuances in swarasthanas and the part played by overtones and harmonics in Karnatic music,” a music she notes that has “no counterpart anywhere in the world.”

She was equally clear about the role of Bhakti, the importance of the Vaggeyakaras’ sahitya, and the true nature of a beautiful voice. Referring to the large body of compositions of not just the Trinity but others from Purandaradasa to Thiruppugazh and Divya Prabhandam, that are the staple of Karnatic music, she emphasises that they attest to “the truth that the songs have been composed not merely to demonstrate the raga-bhava to the listeners. The songs have the higher purpose of directing the minds of the listeners towards God and His manifestations. In short, Bhakti is the key-note of these compositions.”

She says that Thyagaraja lays down “that the man who sings in praise of God is he who upholds Truth. Who is always at the service of humanity. To whom all Gods and Goddesses are the same and who sings with an impeccable voice. From this we understand that truth, service and impartiality should go hand in hand with a sweet voice…A pure mind and a sweet voice cannot be separated from each other…”

At the same time, she implores learners “to give prominence to raga alapana and explore the full possibilities of each raga” and “to devote time to the acquisition of purity in voice and shruthi.” As a student of the mridangam, her control over laya was also perfect, and she never compromised on fully understanding the sahitya of a composition, in whatever language, and doing her utmost to enunciate words and phrases correctly.

MS had a vision for India where Indians would develop a taste for good music and her people would prosper. She made a special appeal to mothers “to take up the sacred responsibility of keeping the lamp of Sangita burning bright in their homes and to instill a love for good music in their children from a tender age. If mothers create this taste for music in the next generation it will spread throughout the country, and ultimately our people will lead good lives.”

The last century marked a period of transition in Karnatic music. In the early 1920s and 1930s when Subbulakshmi began her career, Karnatic music became extremely orthodox in its grammar and the voice of the majority dictated its norms. K G Vijayakrishnan in his book The Grammar of Carnatic Music points out that the women musicians of the 20th century challenged the ‘prescriptive diktats’, led most admirably by Veena Dhanammal.

“Today the sweet/mellifluous styles and the aggressive style seem to have a gender bias with their own characteristics in contemporary Karnatic performances. However if we look back on the practices of the last 50 years, we find that this kind of gender polarity was not so obvious with many women singers of genius exhibiting a remarkable range of distinct styles. It is a pity that what women singers had gained when they had to literally take by force what was considered a male fortress in the past fifty years, producing a wide variety of remarkable women’s style, is now being lost in unnecessary type casting of gender based performances,” he adds.

For many it was impossible to hold the beauty of M.S. Subbulakshmi’s Meera or Shankuntalam in their heads along with her Sankarabharanam. For M.S. Subbulakshmi herself, each of the songs of Meera became her own paeans to her God and a means to unite a country through devotional music.

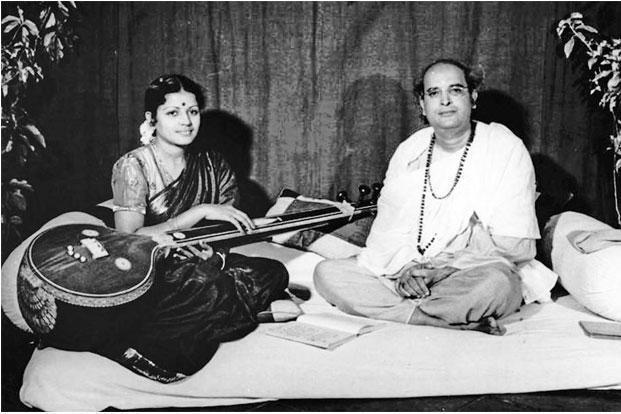

Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, her guru, saw her simply as the one with the superior tanam, chowka kala niraval, perfect diction. “Subbulakshmi has that which is most difficult to reach – sowkhyam (tranquillity). No, it does not come through effort or feeling. It goes beyond the ‘good’ and the ‘fine.’ Very few possess a voice that intoxicates you as soon as you hear it. She did. Have you heard her in the film Sakuntalai? Delightful!”

There was only one code which she lived by. One of acceptance, striving and service. But the world of art in which she lived, did not always show the same character. Sadly, as cultural critic Greil Marcus puts it, “It all comes down to that urge to fascism – maybe a big word to use for art, but I think the right word – it comes down to that urge to fascism to know what’s best for people, to know that some people are of the best and some people are of the worst; the urge to separate the good from the bad and to praise oneself; … what songs people ought to be moved by, what art they ought to make, an urge that makes art into a set of laws that take away your freedom rather than a kind of activity that creates freedom or reveals it. It all comes down to the notion that, in the end, there is a social explanation for art, which is to say an explanation of what kind of art you should be ashamed of and what kind of art you should be proud of. It’s the reduction of the mystery of art, where it comes from, where it goes…”

The problem in the stratification of voices, in arranging them as better or worse, is that one loses the luxury of hearing multiple views – an imperative both in art and society. Isn’t that after all, the contention of many who would want to criticise her, forgetting that they are not following their own rules?

Here is Swami Vivekananda again: “This was the theme of her life work, the burden of her songs, the foundation of her being, the raison d’etre of her very existence – the spiritualisation of the human race.” He was talking about India. Without taking anything away from her musical genius, he might as well have been talking about M.S. Subbulakshmi.

Likewise with Subbulakshmi’s incomparable and immensely valuable rendering of Suprabhatham and Vishnu Sahasranamam. These 1969 recordings are today heard from Thirumala to Badrinath, from East to West, in both sophisticated audio systems and handheld devices of the rich and poor alike.

And it has appealed to the most traditional of Vedic adherents — even the occasional missed euphonic change (the ‘sandhi’ changes prescribed in the sutras for Sanskrit diction) have never mattered, given her commitment to correct enunciation over all and her deep involvement in the chanting.

Bangalore based Vedic scholars and chanters, the Challakere Brothers, widely lauded for their perfect adherence to the principles of Vedic chanting and their recordings of the Vedas as well as the Vishnu Sahasranamam, attest to the impact Subbulakshmi’s recordings had when they were released, as they were growing up in a traditional Vedic family in Challakere town.

The elder of the duo, M.S. Venugopal, who is also a Karnatic music aficionado, says: “We started out by following her style for the Sahasranamam. We immersed ourselves in it. Her Bhakthi and Vinaya, displayed even in her concerts, is incomparable, and this is what gives her renderings a timeless quality.” Adds the younger brother M.S. Srinivasan: “We consider her our Guru, and remember her every time before starting a Vishnu Sahasranamam chant. As for music, we think Saint Thyagaraja only must have sent her to this earth!”

An interesting anecdote during the actual recording itself, shows Subbulakshmi’s great generosity of spirit as an artiste. Radha Vishwanathan, her daughter, has narrated an incident in the rendition of the Vishnu Sahasranama, at the line ‘Amaani Maanado Maanyo’, where Subbulakshmi stopped to catch her breath and only Radha’s voice was recorded. There was a lot of debate if the line had to be re-recorded, after all, this has been the song that has been sung since 1430 AD to wake up the Lord of Thirumala. Subbulakshmi asked the recording to be taken as is. “Let people know that Radha recited it with me.”

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.