Baba, my father, was — is — my absolute favorite person in the world. He was — is — my kindred spirit. We were wallflowers who hung back at dinner parties, often chatting only with each other. We were bookworms who cried too easily. We hated shopping at the mall but loved to linger at the grocery store. We browsed every aisle, white chocolate mochas in hand from the in-store Starbucks. Even after he could no longer eat, Baba made sure the kitchen was stocked with my favorite foods when I visited home. His last words to me before lapsing into the coma that took his life were to ask if I had eaten anything.

My father suffered from PSP (progressive supranuclear palsy), a rare terminal neurological condition. That meant years of watching him decline as his speech slurred and he lost mobility. It also gave me years to think about and try to prepare for his eventual passing.

In my life, my faith (Hinduism) has always been a source of strength and solace. But it was a struggle for me to know what to make of his eventual death. My Christian friends believed they would reunite with their loved ones in heaven. Many of my family and friends, bred on mainstream popular cultural narratives around heaven and eternal life, believed the same thing.

In the Dharma traditions, however, there is no such afterlife or heavenly world in which such a reunion is possible.

The Bhagavad Gita tells us —

Na jaayate mriyate vaa kadaachin / Naayam bhootwaa bhavitaa vaa na bhooyah;

Ajo nityah shaashwato’yam puraano / Na hanyate hanyamaane shareere

(He is not born nor does He ever die; after having been, He again ceases not to be. Unborn, eternal, changeless, and ancient, He is not killed when the body is killed.) (2:20)

Vaasaamsi jeernaani yathaa vihaaya / Navaani grihnaati naro’paraani;

Tathaa shareeraani vihaaya jeernaa / Nyanyaani samyaati navaani dehee.

(Just as a man casts off worn-out clothes and puts on new ones, so also the embodied Self casts off worn-out bodies and enters others that are new.) (2:22)

The Baba I knew and loved — the way his eyes widened and brightened when he laughed, the knobby knuckles of his hands which used to hold mine so tenderly, the voice rusted with love that everyday asked me to tell him about my day, the full-bodied laugh when we watched The Three Stooges — that concatenation of qualities and quirks of personality that comprised my Baba was the ‘worn-out clothes’ that would be discarded between lives. That Baba, that self with a lower-case ‘s’, would, in many ways, cease to exist.

Trishanku’s Heaven

There are heavenly and hellish realms in Hinduism, but they are only temporary. As soon as one’s karma is exhausted, one starts at the bottom again. It is like an endless loop of Snakes & Ladders, a game designed to metaphorize the cycle of life and death. Ultimately, moksha frees one from the game itself.

Even in these transits through other worlds, though, the mortal body cannot be used. The Puranas, sacred ancient Hindu lore, narrate only a few examples of exalted individuals allowed to enter Swarga in their human body. And that, too, only lasts for a time. Swarga is the closest approximation in Hindu cosmology to heaven, except that it is transient and not the ultimate goal of life.

The Ramayana has a fascinating story about Trishanku, a king, who wanted to enter Swarga in his human body. Trishanku’s guru, the great rishi Vasishta, was horrified by the request and forbade the king from pursuing it further.

Trishanku persisted, despite being cursed by Vasishta’s sons. Finally, Vishwamitra, the rival sage to Vasishta, took up his cause. He started the performance of a rite to grant Trishanku passage to Swarga. The devas spoiled the rite. Vishwamitra, an extraordinary yogi, propelled Trishanku toward Swarga through sheer willpower.

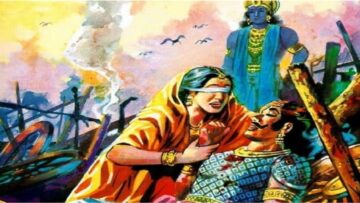

When Trishanku reached the gates of Swarga, Indra and the other devas refused to admit him. He fell headfirst from the skies, crying out to Vishwamitra for help. The great sage suspended the king’s fall as he hovered upside-down midair.

Enraged at the devas, Vishwamitra created a parallel universe that would have a special heaven for Trishanku. The devas pleaded with Vishwamitra to reconsider. As a compromise, the king remained in Vishwamitra’s heaven but was left hanging upside-down as a show of honor to Indra. This become known as Trishanku’s heaven, where one is neither happy nor unhappy.

The cautionary tale warns us to not become too attached to one’s sense of self (that is, self with a lower-case ‘s’). One should not identify too much with one’s name and form or one’s personality. They are no more a part of our real self than our clothing. The wardrobe of our persona will not accompany us into the next world.

It was this notion — the disappearance of the individual self — that I kept coming back to in those years preparing for and then dealing with my father’s death. I understood the philosophy. But I needed something more tangible. I needed to know, really truly know —

Where did Baba go after he died?

Journey through Tibet

The Bardo Thodol (“Liberation Through Hearing During the Intermediate State”) is from the Nyingma tradition in Tibetan Buddhism. It is somewhat misleadingly referred to in the West as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The text details the journey of the individual through the bardo, the interregnum phase between death and rebirth.

I do not believe it was a coincidence that, months before Baba died, I had made an impulsive pilgrimage to Tibet. In ancient monasteries, I bowed my head and chanted for my father. No sacred tradition has delved more deeply into matters related to death and the in-between life than Tibetan Buddhism. My time in Tibet empowered me to let go of my father and prepared me for his death.

Tibetan Buddhism originates from Hindu cosmology and metaphysics. Yet, Hinduism does not go into great detail on the mechanics of death and transmigration. In the Hindu worldview, these concepts are helpful to explain the cosmic play of existence but are not fundamentally real.

The mahavakya are a collection of profound Vedantic sayings meant to lead to self-realization, akin to Zen koans.

One such mahavakya is, Brahma satyam; jagan mithya. Brahman (the Eternal Self) alone is real; the world is of only ephemeral or transactional reality. In the ajatavada doctrine of Advaita Vedanta, nothing is ever subject to creation or destruction. There is only the aja, the unborn eternal. In that light, even the various realms of heavenly or hellish existence are empty and transient.

Pitraloka — The Realm of the Ancestors

In Hinduism, our forefathers — from our immediate parents to our first ancestors — become part of our pitrs after death. They may be in various realms depending on their karma, but a strong thread connects them to us. That thread is rnubandhana, or karmic debt.

Ancestor worship is universal across the indigenous sacred traditions. It was understood that we do not live for ourselves alone. We carry forth the legacy of our ancestors; we are custodians of the earth that we will one day entrust to our children. This link across the generations is a matter of reverence.

Hinduism, one of the last living repositories of indigenous wisdom and practice, places great importance on honoring the pitrs. The sacred Ganga river descended to earth at the behest of a king who wanted to placate his ancestors and immerse their ashes in her waters. Such was the veneration shown to our ancestors.

Before important rites, the pitrs are invoked to bless the ceremony. The sixteen-day pitru paksha period of each year is devoted to making offerings to the pitrs, which includes one’s own ancestors as well as those unnamed pitrs for whom no rites have been performed for whatever reason. By our offerings, we wish to keep the pitrs content and ensure they have no unfulfilled desires that will haunt them. In turn, they watch over us. They live on through our good deeds.

For many months after Baba died, I had variations of a dream.

Baba was at the train station or on the front porch of our home, huddled in his favorite coat and shoes. I was packing his suitcase but could not find his favorite socks. The clock was ticking. The train was about to depart, the van about to leave the driveway. But I was desperate that he should leave with a full suitcase, that he should have no unfulfilled desire. I would wake up right before I found that sock and wonder if I had been too late.

On the tenth day ceremony, a bundle of supplies is prepared for the departed one to carry through the bardo. One of the most cathartic parts of my grieving process was doing this for Baba. Picking an umbrella to protect him from the heat of the sun that used to make him sweat so profusely, a set of clothing that would be comfortable and in his favorite colors, a blanket to warm him at night — the last gesture of love I could offer him.

One of the differences between Pitraloka and heaven as we conventionally think of it is that Pitraloka is impersonal. My father became one of innumerable pitrs once he passed from this world. He exists as a pitr in the abstract, as a benevolent force, as a name in a long lineage. But there is not some physical or subtle world where I can travel to see him. His individual existence as I would recognize him has vanished.

Our traditions are fastidious about ensuring a clean transition between worlds. Too much of us clinging onto them or vice versa can trap the dead here as ghosts. There is the story of the wise king Bharata, who became a forest hermit. At the end of his long life, he became so attached to a baby deer that he was reborn as a deer. Our dharma is to help the dying fulfill their desires so they leave with no attachments or regret, so they are not bound to this mortal world. And, we have to learn how to let them go.

So, I was very careful the year after Baba died, to not call out to him, to not indulge in too many memories, to just pray for him, to send him to love in the abstract.

I reach out to him nowadays but in a different way. The way one sometimes wriggles a toe to test its presence as part of the foot that is part of the leg that is part of the body that belongs to the self. Sometimes, I say his name, Baba. I do not hear his voice or see him or have a conversation with him. It is enough to feel his presence somewhere out there, in some different form or formless. We communicate now in the language of love and offerings instead of words and touch. We coexist on the subtle plane if not the physical. Being sublimated into the abstract makes our connection no less potent.

His blessings were there at my wedding, even though he was not there. His blessings are upon my husband, even though they never met. His blessings made my first novel possible, even though he never read it.

I still pray for him and know that my prayers reach him. The Vedas tell us —

“Whatever is offered to the ancestors … goes to them in whatever form they exist. Just as a calf finds its mother among the scattered herd.”

When a thing exists, when it is real, when it is deep, when it is something like love — it can never disappear. It can only transmute.

He has moved on to somewhere else, somewhere better, somewhere I cannot reach him. The afternoon before the morning of Baba’s passing, I sat with him for a long time. I held his hand and did fierce japa, pouring the mantra into him through our linked hands. I tried to will, with my meager stores of power, a peaceful passing for him, the way Vishwamitra willed Trishanku to enter heaven.

I had a vision then, one not meant to be written of in essays, one that even now renders me speechless and breathless at the beauty and tranquility of it. I saw where Baba would go. And then I could finally let go of Baba’s hand for the last time.

Would You Know My Name if I saw You on Earth?

In his masterpiece of a song, Tears in Heaven, written in the aftermath of the tragic loss of his four-year-old son, Eric Clapton wonders if his son would know his name, hold his hand, recognize him if he saw him in heaven.

I used to wonder the same thing about Baba but in reverse. I used to wonder what would happen if he reincarnated right here on earth and I met him in this life or a future life. What would happen if our karmic bond caused us to cross paths again in this or another world? Would I recognize him? Would he recognize me?

I could never know.

But it started me thinking — how many lifetimes do we live? How many fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, husbands, friends do we make and remake lifetime after lifetime? How many of the strangers that I meet today have been or will someday be family or friends to me?

Perhaps that is the meaning of the Vedic saying, ‘Vasudhaiva Kutambakam’ (all beings on earth belong to a single-family). Every sentient being has been a close relative to us somewhere across an infinite number of lives in the Hindu and Buddhist worldview.

Perhaps the love that I used to uniquely share with my father is meant to be shared with the world.

Just in case, though — if you happen to come across a person full of gentle love, whose eyes go wide and bright every time he smiles, who loves to drink white chocolate mocha with a little sigh of pleasure at the end of every sip, who laughs joyously at The Three Stooges, who asks you every day what you ate for lunch — will you send him some love from me?

(Mahalaya – Pitrupaksh – The Realm Of Our Ancestors was first published here)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.