Yashovati reclined backwards on the quilted throne. Her aching back longed for a cushion for additional support. As if the recent news of Damodar’s demise wasn’t painfully draining her mind, the third trimester of her pregnancy was also bearing excruciatingly on her pelvic bones. She tried to close her eyes and focus her mind on something else, but blurry images of the past week whirled in her subconscious…repeated pleading to Damodar to skip the Gandhara Swayamvar…the pall bearers entering Srinagari Palace with her husband’s corpse…the echoing cries of her mother-in-law…the hurried coronation ceremony and lastly a blurred image of bewildered courtiers as a crown was placed on her head. She dizzily opened her eyes again only to see plush chunks of snow falling outside the palace window. The damp court loomed in and out of her sight.

|

| Dilapidated ruins of the Martand Surya Mandir in Anantnag, sacked by Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in an attempt to convert the population. |

Most of India’s literary past has shared two connected and often interwoven themes, history and mythology; with both overlapping each other at times. One of the biggest criticisms that Indian historical tradition has faced is firstly, the absence of awareness around it and secondly, the lack of unbiased scientific approach in its writing. However, one of the standout compositions that has somewhat managed to escape criticism is Kalhana’s history of Kashmir titled ‘Rajatarangini’. Repeated efforts by historians both within and outside India have allowed us to analyse Rajatarangini in its entirety and seek a glimpse into one of the oldest areas of Indian civilization, Kashmir.

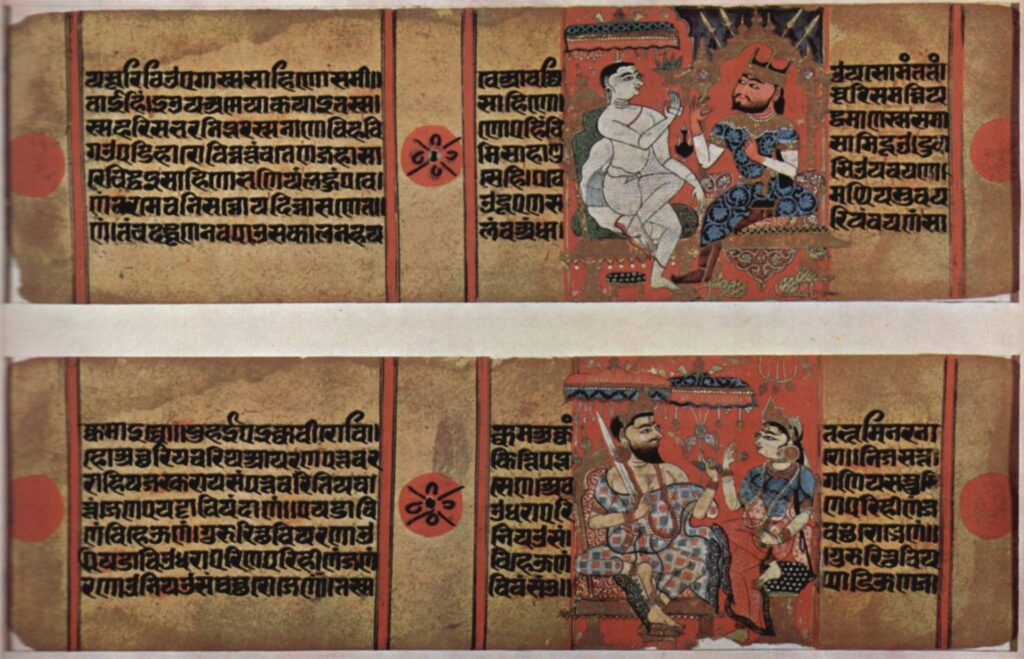

Before beginning the analysis of Rajatarangini, it is necessary to understand the basics of historical traditions in India. Ancient Indian historians and chroniclers preferred the poetic format or ‘Kavya’ as best suited to record history. The skills of the chronicler didn’t simply rely on noting down the facts but also in their ability to connect and rhyme it. As a result, literary and historical culture developed spoken aspects too, where the written piece had to sound sonically pleasing while being recited to the audience which mainly included the royalty and their court. This also came with the usual problems of history writing like exaggeration and flattery to generate a more robust response from the audience. Therefore, most histories from the past are ‘Charits’ (character sketches) that have embedded details of society, culture, religion and beliefs of the time.

|

| A manuscript of the Vikramdeva Charita, Kalpasutra manuscript, written in traditional Kavya format |

It is here that we see the first varying feature of Rajatarangini as compared to conventional histories. Rajatarangini literally meaning ‘river of kings’ is a connected narrative of dynasties that ruled Kashmir, beginning with well-known legends and then aligning with the chronological narrative. It isn’t focused on a particular dynasty or king and wasn’t financed by a court which makes it free of unnecessary bias on the author’s part. Infact this is one of the main reasons why it still survives. The materials written for the delectation of a particular king or court lost relevance over a period of time with the change in power/dynasty. Poets ceased their recitation and only bits and pieces survived as references in later works. Despite this, the few court histories that did survive faced the ravages of time. On the contrary, later authors kept adding on to Rajatarangini, thereby preserving the original document.

|

| Coins issued during the reign of King Harsha of Kashmir, under whom Kalhana’s father was appointed as Dwarapati |

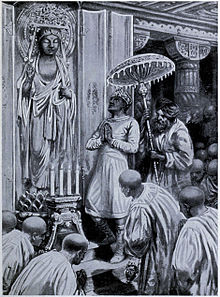

Interestingly, the name of the original author (Kalhana) was deduced from a later version of the book. It is now known to us that Kalhana was the son of the great Kashmirian minister Lord Canpaka who was appointed in the court of King Harsha of Kashmir. The book Rajatarangini was written in the ‘Year 4224 of the Laukik Era’ or 1148-49 AD (12th century). Canpaka was the ‘dwarpati’ or commandant of the frontier defences under Harsha. While Canpaka was away on a mission, Harsha was killed in a power succession. It is interesting to note that Kalhana mentions his father Canpaka as a fervent worshipper of the Nandikshetra in present day Kashmir but his uncle Lord Kanak has Buddhist contacts. Kanak is credited with saving a colossal Buddha image in Parihaspur in present day Kashmir which was their shared birthplace. Kalhana himself was a Shaivite Brahmin (the index of the book contains prayers addressed to Ardhanarishwar) judging by the style of his Sanskrit and was mentioned as ‘dvija’ by his successor Jonaraja who later continued the book.

|

| The Naranag Temple located near Srinagar, constructed by Lalitaditya in 8th century which Kalhana mentions in Rajatarangini |

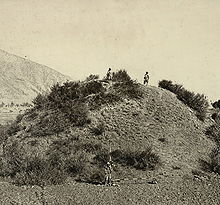

Regardless of his Shaivite background Kalhana shows a friendly attitude to Buddhist traditions in Kashmir. He praises kings from Ashoka all the way down to King Meghavahana for building Stupas and Viharas in Kashmir that sadly barely exist today. For centuries before Kalhana’s time Buddhism and Shaivism had co-existed peacefully in Kashmir. Kalhana refers to Buddha as ‘the comforter of all beings’. Donors of shrines of Buddha and Shiva/Vishnu were often shared. Kalhana mentions King Harshavardhana of Kannauj (who was also recorded by Hieun Tsang), King Kumarpala of Gujarat as financers of Stupas and Temples alike.

|

| Buddhist Stupa Jayendra Vihar at Ushkhur (Huṣkapur-derieved from Huna king Huska) near Baramulla (Actual Name Varah-mula) during excavations in 1869 |

Not a lot is known about Kalhana’s formal education. Kalhana himself mentions familiarity with the 8th century epic Vikramdeva-charita by Kashmirian poet Bilhana, Banabhatta’s Harshacharita, epics like Mahabharata and Ramayana and a general knowledge of Veda and Puran. Kalhana’s plausibility comes from another wonderful source, the Srikanthacharita (1128-1144 AD) which was composed by Mankha, a Kashmirian poet and a contemporary of Kalhana. Mankha gives details of a literary assembly or ‘kavya sabha’ that was organized at his brother’s (Minister Alamkara) house. Modern historians like Cunningham and Professor Buhler were initially surprised to see Kalhana absent in the list of the guests. However, they soon found reference of a poet named ‘Kalyan’ that Mankha describes as a master of Kavya with a style similar to the 8th century poet Bilhana. It so happens that the slurring of the Sanskrit word ‘Kalyan’ in Prakrit created the alternate name ‘Kal-an’ or ‘Kalhana’. Some etymologists have argued that Kalyan’s style being similar to Bilhana created an alternate combined nickname in his literary circle i.e. Kalhana.

|

| Patanjali’s Mahabhashya was one of the books discussed in the ‘kavya sabha’ mentioned by Mankha. Interestingly, Patanjali himself was a Kashmirian too. |

Kalhana’s age during the composition of the Rajatarangini is also debated. Kalhana’s description of the troubled times in Sri Nagar in the spring of AD 1121 before the restoration of King Sussala and the attempts of usurping power by Bhiksacara (characters that will be made familiar later) is given in great detail in Rajatarangini. Not only that, Kalhana also has a very mature eye witness account of the same, so it is unlikely that he was a child at the time. Infact Kalhana mentions the beginning of 12th century as being a troubled time for Kashmir. He describes the tyrannical rule of King Harsha, heavy fiscal extractions and persecution of the Damara or landowning class of Kashmir. The Damaras in response opposed any king-in-power by repeatedly propping up their own alternate-puppet kings hoping to initiate a succession war.

|

| Sculpture of Buddha on Mount Meru from Kashmir, 7th century AD |

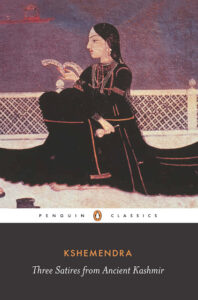

Kalhana himself never held office or official position under any king, therefore he is very vocal in his criticism of the various kings and their administration. Kalhana criticizes the lack of military spirit among Kashmirians and praises Rajputs for it, but at the same time he criticizes Rajputs for claiming superiority than others. He mocks the indifference with which the masses welcome change. He also voices his aversion and contempt for the Damara class, their coarseness and boorishness and terms them ‘dsyus’ (‘robber’ not slave). He makes satirical allusions to the officials and their greed. Kalhana mentions that the ‘old royalty’ (comprising of Brahmins and priests) repeatedly held fasts against political killings that were greatly feared by the masses and put the political spectrum on track for short terms.

|

| Kshemendra, famous 11th century poet from kashmir has authored several works in literature |

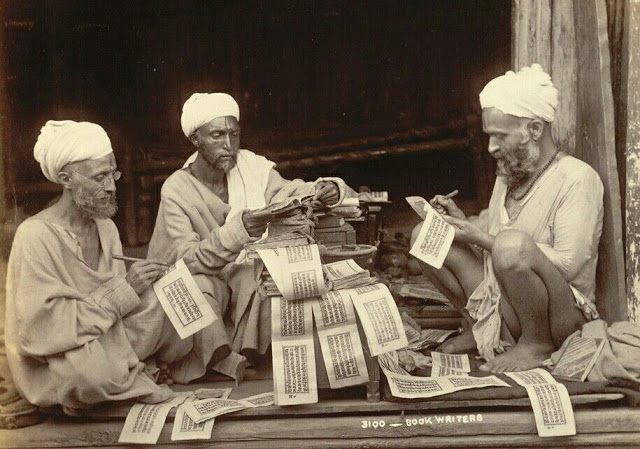

Unlike traditional Kavya, Kalhana rarely focuses on embellished language and beauty of nature and limits himself to essential commentary. However, the text continued to be didactic (i.e. written with an aim to provide moral preaching) as he frequently compared immoral political events to instances from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Speaking of morality, Kalhana was also aware of the value of historical impartiality, therefore he mentions sources of borrowed facts. He mentions Suvarta, a previous author who had ‘not so aptly’ condensed previous history into a handbook. Kalhana also inspected 11 works of former histories of Kashmir. Kalhana also used Ksemendra’s list of kings called ‘Nrapavali’ and another text named ‘Chavillakara’ by Padmamihira .

|

| Kashmiri Pandit Scribes copying Manuscript, 1890s |

One of the most well-known of sources that Kalhana mentions is the Nilamata Puran which is an ancient treatise on the geography, culture and history of Kashmir. The Nilamata Puran begins with a dialogue between Rishi Vaishampayan and King Janamejaya who enquires about the absence of Kashmir Kings in the Mahabharat war. The Rishi mentions that following the death of Kashmir’s King Gonada (friend of Jarasandha) and his brother Damodar by Balarama and Krishna respectively, the pregnant queen Yashovati was crowned Queen as there was no heir yet. Yashovati’s son King Gonada the second was still minor during the Mahabharat war and was therefore debarred (or rather not expected to) participate. Regardless of its historicity, the Nilamata Puran is essential for the references to Kashmir, war etiquettes, surprising phenomenon like crowning a pregnant queen, geographical details (like Gandhara, present day Afghanistan) and Kashmir’s natural beauty.

|

| Sharda Peeth, mentioned in Nilamata Puran |

Rajatarangini as a book comprises of eight cantos (volumes). The first three books cover the great period of Ancient Kashmirian history beginning with mythological stories of its creation. However, it does point out that Kashmir valley was created after the draining of a lake, a fact that geographers have also alluded too. The book begins with a legendary date of the crowning of King Gonada the first which is contemporary to the accession of Yudhishthir of Mahabharat (653 Kali Age). The first three books contain details of the reign of Gonadaya dynasties. They have long dynastic lists prepared more or less with legendary traditions and anecdotes. The first three books are primarily referred for studying cultural and literary themes. Books Four to Eight (beginning from the Karkota Dynasty to Kalhana’s own time) contain clearly verifiable details with immaculately detailed chronology of reigns of Kings and Queens of Kashmir (down to months and days).

|

| Geographical Extent of the Karkota Dynasty |

Kalhana also followed the ancient system of not mentioning ‘century’ in Laukik era, but since the narrative is chronologically connected one can easily count forward or backward from the few dates that are given. The last four books are very accurate with chronology. The commencement of Laukik era is dated at 3076-75 BC. The months in Laukik era follow the Purnimanta or lunar scale of month calculation.

Within the first three books the important figures of history include King Ashoka, who Kalhana mentions in great detail as the upholder of morality and credits him for his Buddhist inclinations. The dates of Ashoka were unquestioningly quoted from an unverified source that ended up placing him almost a thousand years before his time. The same issue was seen with the details of Huna kings Huska, Juska and the well-known King Kanishka. This gives us the first major criticism of the first half of Rajatarangini. It is also argued that chronological errors occurred due to wrong conversion of dates from different scales, since every detail about the said kings are correct except the dates. We also see that Kalhana quoted dates from the sources he mentioned; therefore, the dates would’ve seemed correct to him since they were wrong within the primary source itself.

|

| Artistic Visualization of Kanishka initiating Mahayana Buddhism |

Another criticism of Kalhana is his reproduction of miracles, exaggerations and superstitious beliefs in the early parts of Rajatarangini without a mark of doubt. It is possible that the data before the 6th century was already so scarce that Kalhana had no choice but to replicate whatever little material was available to him. However, it doesn’t allow us to ignore Kalhana’s details of 300-year long reign of King Ranaditya, mythical tales about Naga vengeance, presence of animagus and shapeshifters that he casually mentions in the first three books.

|

| A ninth century carved idol of Devi Sharda (Saraswati) from Kashmir |

It is also important to note that up till Kalhana’s time Kashmir was topographically isolated. The Sitasarita or ‘land of Sharda’ not only enjoyed long immunity from invasions until Kalhana’s time, but it also allowed dynasties to enjoy long periods of internal sovereignty. Despite that, Kalhana’s geographical viewpoint wasn’t myopic. He frequently mentioned places in southern parts of subcontinent, connections with Kamrup (present day Assam), Gandhar, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, rivers and places of Shaiva worship in mainland India. His opinion of Kashmir was very much based in reality.

In the next part of the blog I will discuss the second half of Rajatarngini with a greater focus on its content and historical personalities.

(This article has been republished from sinoperdark.blogspot.com with the Author’s permission)

(Featured Image Credit: TFIPOST)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.