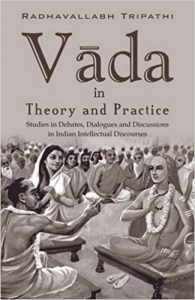

Book: Vada in Theory and Practice

Author: Prof. Radhavallabh Tripathi

sargāṇāmādirantaśca madhyaṃ caivāhamarjuna, adhyātmavidyā vidyānāṃ vādaḥ pravadatāmaham

Of creation I am the beginning and the end and also the middle, O Arjuna. I am spiritual knowledge among the many philosophies, arts and sciences; I am the logic of those who debate.

[Gita: 10: 32]

In the history of Indian philosophy there were two fundamental streams of progression: darsana and vada. The former with its six main schools is widely known, studied and appreciated across the world, the later has been relegated to footnotes of history. The previous cursory mentions of vadashatra (science of debates and discussions) comes from the works of Amartya Sen and A. Raghuramaraju, but it is only now that connoisseurs of Indian philosophy can delight in this beautiful, exhaustive monograph on the art and culture of debating as it has been practiced in this subcontinent from a very ancient time.

Professor Radhavallabh Tripathi, author of 162 books, and 227 research papers and critical essays, is the Vice-chancellor of the Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan. He is highly regarded for his tremendous contribution to literature and studies in Nāṭyaśāstra (theory of drama) and Sahityasśāstra (theory of literature). He is also the recipient of 35 national and international awards, covering various distinctions relevant to the field. Easily, Prof. Tripathi’s credentials are ideal for a book on this topic.

Professor Radhavallabh Tripathi, author of 162 books, and 227 research papers and critical essays, is the Vice-chancellor of the Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan. He is highly regarded for his tremendous contribution to literature and studies in Nāṭyaśāstra (theory of drama) and Sahityasśāstra (theory of literature). He is also the recipient of 35 national and international awards, covering various distinctions relevant to the field. Easily, Prof. Tripathi’s credentials are ideal for a book on this topic.

In any branch of Sanskrit literature the volume of secondary texts and commentaries far outnumber the primary sources. In the prologue of this book, which by the way can stand on its own merit as a terrific premier to the idea of vada for those who maybe unaware of it, the author elegantly quotes the legendary Mallinātha Sūri, critic per excellence, poet and commentator of five Mahakavya-s, from the later’s commentary on the Kiratarjuniyam clarifying that he has relied heavily on original sources.

“Here I have explained everything just by paraphrasing, have not written anything without the base of the original and have not said anything unwanted.”

Debate as Philosophy

vade vade jayate tattvabodha

[after going through a series of vadas, true knowledge is acquired].

Indian society and culture has always shaped itself through a process of a friction and assimilation of differing viewpoints. From an ancient hoary past debates and discussions have helped create and maintain a democracy in thought and belief-systems. S. Radhakrishnan too had noticed the same trend and remarked:

“Helped by natural conditions, and provided with the intellectual scope to think out the implications of things, the Indian escaped the doom which Plato pronounced to be the worst of all, viz, the hatred of reason.”

Authoritarian regimes, dictators, and thought-police do not allow debates and questions. They love conformity and unquestioned obedience to authority of any form, be it a government, an individual, an institution or even a certain manner of thinking. Any divergence from the restrictive paths of monoculture invites severe reprisals from whatever powers feel threatened by an atmosphere of open debates. India, and specially ancient and medieval India, was free from such thought-crippling malice.

From the Socratic dialogues to the formalization of dialectic methods by Aristotle, Greek culture, which is the substratum for Western philosophy and modern Science, stands firmly on the idea of debates and discussions. Dialectic (dialektikḗ; related to dialogue) therefore was the “art of discussions, debate, controversy, method of argument or disputation, process of discursive or conversational thinking” divorced from emotionalism, and rhetoric.

In India one of the earliest term for debates was ānvīkṣikī, which means logic or logical philosophy or reviewing. Speech was considered not merely as a human device of communication, but the very means to liberation. A theory is born in the mind of some genius, but it grows and developed and stands on its feet, only by passing through the fire of debates and discussions, which lead to further fine tuning of the ideas and concepts, eventually leading to a realizing of the Ultimate Truth. This one overarching love for an Eternal Truth has been the fundamental movement across Indian thought, and reflects abundantly in and through its myriad manifestations in literature, arts, sciences, philosophy etc. Vada – and we shall see how ānvīkṣikī changed to Vada – therefore is not merely about proving or disproving an intellectual opponent, but also a means of self purification of ideas which would eventually lead to clarity and realization: tattvabodha. Hence, says prof. Tripathi, Sanskrit pundits have a verse to represent this idea:

vAde vAde jAyate tattvabodhah

[after going through a series of vAda-s, true knowledge is acquired].

ānvīkṣikī started an a mixture of Samkhya, Yoga and Charavaka ideas. Kautilya opined that ānvīkṣikī’s chief purpose was to review and investigate the claims of other disciplines in the cold light of reason and logic. The illustrious court poet, critic and commentator of the Gurjara Pratihara dynasty from 10th century, Rājaśekhara, in his Kavyamimamsa (880 – 920 CE) writing about the different vidya-s (branches of learning) says this about ānvīkṣikī:

“The ānvīkṣikī is divided into two parts – purva-paksa (prima facie view) and uttara-paksa (rejoinder). Buddhism, Jainism, and Caravaka philosophies are included in purva-paksa and Samkhya as well as Nyaya and Vaisesika in uttara-paksa. Taken together they form the six argumentative systems.”

Purva-paksha in Vada required that the participant must represent the views of the opponent with as much accuracy and comprehension, and without injecting his own bias, as far as possible. This love for accurate representation has helped many modern scholars and Indologists to recreate the ideas powering entire sub-schools of philosophy which have been lost in time.

Nyaya is one of the six orthodox systems of Indian philosophy

What was ānvīkṣikī in BCE soon became a synonym for Nyaya when Gautama in his Nyayasutra-s, the most authoritative tome on Nyaya, argued that like ānvīkṣikī, his system of philosophy was non-different from and singularly devoted to the art of logic and argumentation. In the Mahabharata Nyaya is used to denote the proper and acceptable rules of debates and discussions such that efficacy and logic of the argument cannot be questioned. Of course Nyaya has also been defined as an adhyatmavidya, science of spirituality, but the methods and epistemology it developed was clearly borrowed from, it not an entire replication of, the earliest ānvīkṣikī methods in theory and practice.

The term Vada comes from the root (-vad) meaning to speak. Dictionaries define Vada variously as speaking of or about, causing a sound, playing, advice, council, speech, discourse, talk, utterance, statement, thesis, etc. The term shastrartha which is in vogue today only came about in the nineteenth century for “vada in a limited sense”, that of scriptural debates in a public platform or in writing. However, during the Vedic era the more popular term for debates was brahmodya, a terminology denoting any assembly or gathering of the learned to discuss matters of ontology (the nature of reality) and epistemology (method and means of gaining knowledge). Apparently, these were peaceful, sober gathering of like-minded individuals with a love for abstract or spiritual thinking. The gathering itself was called brahma-samsad, whereas those dialogues involving heated exchanges were called vakovakya. But these were the ancient times. As the six systems of Indian philosophical approach became systematized, vada gained popular currency as the right word for discourse and debate. Other synonymous terms used for vada over the ages were shastrasabha, sastra-pariksas (examination of scholars through debate), vakyartha-sabha etc.

Parallel to the tradition of Vada we had the idea of darsana or those schools which were to lead men towards enlightenment and salvation. Today India runs of belief. We are often told what is the use of questioning and debates. This dichotomy, however, was a later development, for Vada had historically acted as a bridge through which the epistemological system of pramana-s culminated into moksha using the study of darsana. The Brhadaranyaka Upanishad says: atma va are srotavyo mantavyah (the Self must be listened to, must be contemplated upon with reasoning). Manana, which has now become an established method in the Adwaitic system of Shankara, contains in its essence the idea of rational and critical thinking to arrive at a higher understanding. And critical thinking, attitude of questioning is the seed of all vadas.

Epochs of Debate

The author creates a unique and useful classification of debates based on the different epochs of Indian history: Mantra-kala (Age of Revelation : 3000 BCE to 500 BCE), Tarka-Kala (Age of Arguments : 500 BCE to 1000 CE), Vistara-Kala (Age of Diversification : 1000 CE to 1800 CE), and finally the modern age starting from 1800 CE.

Hanuman painting by artist Appam Raghavendra. Source: Google Image Search

First period deals with the debates that occurred during the earliest Vedic age whose traces can be found in Upanishads and Veda Samhitas. Debates and discussions automatically imply the existence of multiple competing schools. The Upanishads seemingly makes references to different philosophical sects with self-explanatory names like Niyativadins, Kalavadins, Svabhavavadins and Bhutavadins. But Mantra-kala does not end with the Vedas, it continues right upto the debates found in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well.

Sometimes a debate or discussion may not be with an opponent but could take the form of an internal soliloquy. The best example of this comes from Hanuman, who, unable to find Sita, enters into a long pensive dialogue with himself toying about the various future paths he may adopt, all of which aimed at some form of scripturally sanctioned renunciation or death, should be fail in his mission to locate Sita.

Again during the unsavory episode of Draupadi’s humiliation in the court of the Kuru-s we find the royal heroine asking some of the most complex question of Dharma and conduct to the august assembly of elders. Bishma is perplexed and fumbles a feeble reply that Dharma is too subtle and he is unable to decide which side is correct. Vidura and Vikarana (brother of Kaurava-s) come to Draupadi’s defense. The whole Kuru royal court is turned into an impromptu debate assembly where not only the fate of a wronged heroine is being decided, but destiny of the two most powerful royal forces are being re-written. In retrospect, readers are made to realize that this one debate was possibly the most important debate in the history of Indian civilization, for had the participants present inside the royal court decided that Draupadi cannot be subjected to such humiliation, it is likely that the terrible war of Kurukshetra could have been avoided. Vyasa creates the scene with exceptional finesse and clarity where Draupadi utters these remarkable words on the nature of dharma and debate:

“An assembly not attended by elders is not a proper assembly for debate and men who do not speak dharma are not elders. The dharma that is without truth is not dharma, and the truth imbued with deception is not truth.”

But more crucially the arguments and counter-arguments on that fateful day followed closely the method of five-member syllogism, that would later go onto become a systematic part of Vada-s in medieval India. Some of the categories of Vada like tarka, jalpa, vitanda, niryana, praana, nyaya, anumana were already mentioned in the Mahabharata. Later as the Nyaya school developed its own structure, 14 of the 16 essential categories within its fold were related to the art of debates.

While Vada broadly meant discussion, jalpa is what we would consider as debates in modern times, and vitanda is cavil – the technique of raising trivial, circuitous objections. All these three again were included in the large category of Katha (conversation) which was a generic term used for any kind of discourse. Then there were chala (trick), jati (spontaneous counter-argument to prove futility of example or examples derived from hypothesis; spontaneity, or instant conception, is the root of the name), nigrahasthanas (clincher arguments, for example the line of questioning that Gargi subjected Yagyavalka to was leading to a nigrahasthana) and hetavbhasa (fallacy) . While Jalpa was considered as a concealed style of debate, Vitanda was the real destructive force in the arena of India debaters. An expert in Vitanda would not argue to prove himself right, he argues to prove the opponent wrong, which meant he may never clearly state his own position, but will continue finding endless flaws in the other’s idea. Exhaustive texts were written in the genre of Vitanda. Again, we are informed, that Vitanda was further subdivided into two styles: a higher form aimed merely to prove the opponent’s philosophy wrong, and a lower form which is nothing more than sophisticated quibbling. Śrīharṣa from 12th century India referred to the second class of vitanda specialists as durvitandikas!

Tibetan Buddhist monks practicing philosophical debates.

Perhaps the most famous proponent of the Vitanda style of debate was the celebrated Madhyamika philosopher from 1st century BC, Nagarjuna. Madhyamika adherents believed that the fundamental nature (svabhava) of all phenomenon (dharma) is essentially emptiness (Shunya). The easiest way to establish this theory, accordingly, was to be free from all preconditions and standpoints.

“When one accepts any standpoint, one is captured by the cunning poisonous serpent of the impurities. Those, having their minds cleansed of every standpoint, are not captured.”

Madhyamikashastra.

Nagarjuna’s principal approach to debates was deconstructing all labels and opposing ideologies by establishing inherent contradictions in them, while restraining himself from adopting any counter-thesis. He had essentially “no-position”. His fame and authority spread so easily that many considered him as a second Buddha. From Nagarjuna started a long glorious tradition of debates between the Baudhas and the Nyayika scholars. The first challenge to Nagarjuna was thrown by Gautama of Nyaya fold. Then came Vatsayana who is ironically famous these days for the Kamasutra, but was actually better known during his lifetime for his exhaustive rebuttals to the Madhyamika school. Meanwhile, Dinnaga from the Madhyamika tradition joined the debate and gave counter-arguments to Vatsayana, which was again challenged by Udyotakara from the Nyayikas, and then Dharmakriti, one of the most feared names from the Buddhist side fired sumptuous logical missiles against Nyayikas in the evolving sequence of arguments and counter arguments. Eventually Vachaspati Misra and Kumarilla Bhatta (famed authority on Purva Mimamsa) continued the debate against the Buddhists. From the Buddhist side Bhavaviveka and Shantarakshita, another heavyweight philosopher, joined the war of logic and polemics, who not only turned his critical gaze on Nyaya and Mimamsa, but also took a hammer to Samkhyas. Thus for a good part of 600 to 700 years a terrific and fierce debate raged across the Indian intellectual landscape between followers of Baudha dharma and those schools which traced their origination to the Vedas.

With every new iteration of the debates, not only were the opponents being attacked but each philosophy in itself was getting more refined as loopholes and contradictions which would get exposed by the verbal friction were being continously plugged. Meanwhile the Caravaka system resurfaced in the Indian intellectual sphere invigorated by Jayarasi Bhatta who flourish between 770 CE – 830 CE. Jayarasi was trenchant critic of all other systems of thought, and himself being a complete non-believer and a nihilist. His treatise from the Caravaka point of view, Tattvopaplavasimha, established him as an exceptional master of vitanda style of debate, wherein he would demolish – at least that’s what he thought he was doing – every other epistemological method starting from Nyayas to Baudhas to Mimasakas to Vyakarana specialists, to Puranas etc. He pejoratively titled Kumarila Bhatta’s arguments as balavalgitam (child’s quibbling), while Vijnanavada (another sub-school of Buddhism) was to him mugdha-vilasita (fancy of fools). In that climate of attacks and counter-attacks, such criticism of course would not be allowed to pass unchallenged. Nyayikas in turn called Jayarasi an animal, fool or a child, depending on whatever suited the context of arguments best! But Jayarasi was an equal opportunity critic, he spared none. Being a fundamental nihilist his first attack was on Brhaspati, who was the ancient preceptor of the Caravaka system.

Celebrated Debates, Caustic Debaters

Debates, like debates today, were not always pleasant and civil. Often the vadin (proponent) and prativadin (opponent) stood before each other with verbal daggers drawn. Frequent pejoratives were hurled, caustic satires used, every tool in the arsenal of language was fashioned into a weapon for attack. Winners were crowned with glorious epithets. Dharmakriti of the Buddhist camp was known as vadimukhya (chief among debaters), vadipungava (best of debaters), and vadivrishava (bull among debaters). His attitude and casual irreverence towards opponents further added to his fame and charisma. The fiercest of debaters always did an intensive study of the opponent’s school of thought. Purva paksha did not mean just a superficial understanding of the other’s view, but rather to put oneself in the opponent’s shoes and think and comprehend the philosophy as a believer in the system would do. This necessity to correctly understand and accurately record other views have proved a boon for scholars of today. Many lesser known sects like daivavada (fatalism), svabhavavada (naturalism), kalavada (pessimism), purusakaravada (activism) that flourished during medieval and ancient India, along with their tenets and proponents, would have been lost in time had not their ideas found place in the purva paksa part of the debates documented by people like Haribhadra and Vatsayana. Kumarila Bhatta enrolled himself as a student in Buddhist Nalanda to learn the nuances of Baudha dharma before he would emerge as a champion critic of the system and a bold defender of Mimamsa. By 7th and 8th century even the Pallava courts in South India turned into vibrant centers of theological debates. Though it would be difficult to select merely a few names from this never ending galaxy of greats, Prof Tripathi specially mentions Badrayana, Vatsayana, Nagarjuna, Dinnaga, Kumarila, Prabhakar, Dharmakriti, Shankaracharya and Udayana as arguably the greatest vada geniuses from medieval India.

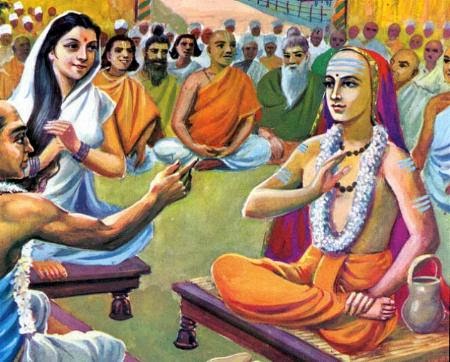

Painting of Adi Shankara debating Mandana Misra

The story of Indian debates however became famous in popular mind with the advent of Adi Shankaracharya in 8th century whose system, or some variant thereof being near ubiquitous today, and Shankara himself attaining to a status of a highly revered spiritual and metaphysical genius. His journey of Vada, also known as digvijaya, covered the whole of India where he would go from one place to another challenging rival philosopher’s. Madhava, the author of Shankaradigvijaya mentions that Adi Shankaracharya entered into debates with poets and philosophers like Bana, Dandin, Mayura, Abhinavagupta, Sriharsa, Bhatta Bhaskara and Udayanacharya. This is most likely an extrapolation narrative, for none of these names were contemporary to Shankara. But the debate about which there is no confusion or doubt that it took place, and one which remains etched in our collective psyche as nothing short of legendary, was Shankara’s challenge to Mandana Misra, one of the most erudite Mimasaka scholars of that age. Shankara is said to have spoken these words to Mandana:

“Let there be vadakatha (debate) between us. Let the pains taken by us in scriptures fructify.” And Mandana Misra replies, “No doubt, I will enter into vada with you.”

Each of the two parties, referred to as the vadin and prativadin, would first furnish the pratijna (thesis), and the pramanas (means of knowledge) which they deemed acceptable. And then they would decide the terms of reference for victory. In this debate Shankara declared if he loses he will give up his saffron robe and become a householder, and Mandana declared that if he lost the debate he will give up life of a householder and become a monk. However, the ancient law that a householder cannot renounce without permission of his spouse was not to be overruled. Finally, a good debate must have judge and jury. Shankara agreed to the nomination of his opponent’s wife Bharati Misra as the adjudicator. The debate went on for many days until finally Bharati conceded that her husband has been defeated but not completely. Since she is half of her husband, now Shankara must debate with her too. In some accounts Shankara was reluctant to enter into a debate with a woman, when Bharati reminded him of the excellent questions which Gargi had thrown at Yagyavalka in an earlier era.

Shankara’s dialectic method involved arguing through textual authority, and professor Tripathi asserts, this often involved impromptu definition or redefinition of texts done in the light of Shankara’s own theory. For example one passage in the Brhadaryanyaka Upanishad declares the method of begetting a girl who will become a great pandita, or scholar. But Shankara asserted during the debate that since women are barred from vedic study, he will reinterpret the verse to mean that this ritual results in the birth of a daughter who will turn out to be a great manager of the house!

As prolific as Shankara was for the Adwatins, equally stellar was Udayanacharaya for the Nyayikas, who was born near Darbhanga area of Bihar in the second half of the 10th century. Several stories of his public debates with other philosophers is well documented. By this time Nyaya had morphed into Nvaya-Nyaya (the new Nyaya with some technical theological differences), and Buddhism had declined from India, so the vigor of debates entered a low phase. One interesting incident however needs mentioning. Udayana is said to have defeated a pandit named Hira, in the court of the King from the Kanyakubja area. Hira was so perturbed by the loss that he devoted all his life in training his son to become a legendary vadin who can vanquish Udayana. Sriharsa, Hira’s son, grew up to be an intellectual giant of his time, but unfortunately Udayanacharya had already passed away by then. Not to be deterred, Sriharsa quickly started the work of demolishing Udayaya’s impressive bevy of texts, and in this way perhaps avenged the humiliating defeat his father had faced many decades earlier. This how seriously debates used to be taken in the Indian tradition.

After Udayacharya Indian spiritual landscape saw a great rise of Bhakti Vaishnavism, where debate was not specifically encouraged as before. On the other hand by this time some syncreticism was also being attempted between different schools of Vedanta. Battles of intellect gave way to a rise in faith-based religious systems. But there was one place where the Bhakti Vedantins would not allow any sympathetic approach: when attacking Shankara’s Adwaita. Their stalwarts found Adwaita Vedanta uncannily similar to the Baudha ideas and started a relentless attack on fundamentals of Adwaita. Madhva of the Dwaita system posited the strongest challenge to Adwaitins using a potent mix of rational epistemology, ontology and dialectic methods to establish a clear difference between God and the world. Simplified, his fundamental strain of thought was this – if there is only Brahman and nothing else, who then is making this statement that there is only Brahman and nothing else? Madhva and his followers like Vyasatirtha, Jayatirtha carried on a campaign of ruthless attacks on Shankara’s monism, directed both at the theory and the person, naming Shankara a prachanna baudha or disguised Buddhist. Adwaitins in turn responded by calling Madhva scholars as prachanna tarikiks (disguised rationalists, implying no spiritual merit). Of the various actors who participated in this dwaita-adwaita clash, one name stands out for his exceptional brilliance in dialectics.

Painting of Madhvacharya

Vadiraja was born in a village of Huvunkare near Kumbhasi in South Kanara district of Karnataka and become the 12th pontiff of the Kumbhasi Matha established by Madhva. His debating skills and the robustness of arguments earned him the epithet of Prasangikabharana (Ornament of Polemics). Vadiraja’s favored style of argumentation involved use of what is called vakovakya alamkara. Apart from authoring many classics he also reinterpreted the Upanishadic aphorisms in the light of Dwaita philosophy.

The critical challenge he threw at the Adwatins, and it was a very powerful attack, was eventually responded to by a scholar from Bengal, an ex-Nyayika who had converted to Adwaita and relocated to Kashi, and who before his conversion never spared Adwaitins, named Madhusudana Saraswati.

Madhusudana was born in Faridpur of Bengal, and employing his superlative skills of vada, wrote a line by line rebuttal to Vadiraja in his much celebrated text named Adwaitasiddhi, which, served a dual purpose of attacking Madhva’s ideas while presenting a formidable restatement of Awaita Vedanta. A counter rebuttal to Madhusudana came from Ramarya, who was Dwaitin, but had disguised himself as a student of Madhusudana in order to learn more about Adwaita theology, following the earlier tradition among great debaters. Madhusudana makes a sarcastic remark on a kumati (ill thinking individual) make pseudo-refutations, which scholars believe was a reference to Ramarya. Tulasidas was a contemporary of Madhusudana. His Ramcharitmanas had initially draw severe criticism from the assembly of scholars in Kashi for degrading Rama by using a colloquial language. It was only after an intervention by the redoubtable Madhusudana, that the controversy was laid to rest and the text went onto become the de facto scripture of the Gangetic plains of North India. Today Adwaitasiddhi is considered a classic of Adwaita Vedanta. Even the most popular Gita Dhyana which millions of Hindus read before chanting the Gita was composed by the same Madhusudana Saraswati.

Topics of Debates

Given the vigorous culture of debates it is reasonable to assume that the topics of debate were also appropriately varied and diverse. It started with the inherent clash between karma, jnana and faith, moved into debates over idealism and materialism, nature of reality, scriptural authority, theories of knowledge, causality, God, idea of Moksha, politics and governance, caste system and its validity, dharmashatras, rights of women, etc.

Prof Tripathi reminds us that sometimes the old themes would resurface with new actors in the debates. For example the first clash between Buddhists and Nyayikas was basically a debate between idealism and realism, the later debate between Dwaita and Adwaita too was fundamentally around the same issue. This constant atmosphere of debates, of questioning and counter-questioning itself led to a tremendous refinement and sophistication in each philosophy. Nothing was static, debates do to thrive in stasis. The Dharmashatras too kept evolving based on the critical challenges they faced when a new philosophy appeared on the scene. Revisions made in the last millenia of the BCE era continued to be tweaked and reinvigorated with fresh leash of arguments and laws. While some traditions centered their worldview around the varna system and patriarchy, an opposing school would overrule such hierarchies with utmost nonchalance. What was tradition for one sect, become heterodoxy for another. Badrayana’s postulates stood in conformity with the laws of Manu, yet Badrayana’s ideas were specially critiqued by philosophers like Bhaguri, and indirectly challenged by spiritual classics like the Gita. Debate over Manu’s law book also stretched for long, with the emergence of the Jaina and Baudha system, necessitating the reformulation of laws over and over. Competing with Manu there were other juristic documents in the Dakshinapatha (South), Magadha, Gauda and Panchala desha. Innumerable smitikaras like Yagyavalka, Parashara, Katyayana, Sankha, Atri etc provided varying juristic framework for the vast population of this subcontinent. It was later during the era of Warren Hastings that Manu’s law’s were picked up from the available dharmashastras and elevated to the position of universal authority.

Painting of Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna

The Tantric schools which emerged in the late medieval period rejected the Vedas and the caste system while created a new schema of spirituality. In short there was no subject, no text, no idea which could not be analysed, questioned and challenged.

Least readers get the impression that debates were merely confined to the high scholars, the book records interesting anecdotes about their use in ordinary culture. Till a few centuries ago many Brahmin families when deciding matrimonial alliances would engage pundits from their school of thought who would debate with pundits engaged by the other party, and depending on the fluency and vigor of the vada, decide if the martial alliance was acceptable to them.

Conclusion

Those who love philosophy and the progression of philosophical thought in the Indian subcontinent, and the frictions that shaped the final form in which we find the texts and theology of different schools of Dharma, would find this book absolutely superlative. Specially, given the scanty literature present on the history of vada, this book assumes an even greater significance in documenting such a unique and longstanding tradition of contrarianism which fueled our greatest minds since at least 3000 years. In this age of social media, fleeting attention-spans and outrage model of argumentation, the book reminds us that we are inheritors of a robust legacy of amazing debaters wherein each would take great pains to prepare themselves before engaging in a verbal duel, that it’s crucial for us to remember, as the old masters did, that nothing can be taken for granted without letting it pass through the sieve of threadbare analysis, and finally, one must engage in a thorough study of the opponent’s ideas from the opponent’s point of view before one can hope to pose any real challenge to a particular line of thought or worldview. When intellectual rigor is prized over superficiality it results in an output which has a long shelf life, unlike quick outrage, and childish ad hominems which fall as swiftly as they rise, leaving no perceptible mark on the march of ideas. But above and beyond all this, even more fundamentally important for us at the individual level is to question our own assumptions on various subjects and keep rejecting, modifying and refining ideas till we reach the Truth. Perhaps this is why Krshna specially singles out Vada as one of his Vibhutis in the Gita. May the debates never end, may we never be scared to question, may the intellect never rust in dead waters of conformity.

Note: Indic Academy is hosting a two day workshop on Vada by Professor Radhavallabh Tripathi. More details can be found here.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.